|

RESEARCH ARTICLE | SHORT  |

Operational flood forecasting in Denmark - integrating groundwater and surface water

Abstract

Most operational flood forecasting systems provide predictions of pluvial and fluvial floods, often neglecting groundwater flooding. Groundwater-induced floods can occur when prolonged rainfall, high river stages or elevated sea levels raise the groundwater table above the surface of the land, often occurring in low-lying areas or areas with specific soil and land-surface conditions. This study presents an operational, national-scale, integrated flood forecasting system that combines surface water and groundwater components – such as river discharge and high groundwater levels – to assess flood risk in Denmark. The system has been proven to effectively capture peak river flows and elevated groundwater levels, as it did across the country during the winter of 2024, and provide local-scale insights, as exemplified during a specific flood event in Varde, west Denmark. This study demonstrates how groundwater flooding, often neglected in operational forecasting, can be effectively incorporated at a national scale to support more informed flood management.

Citation: Liu et al. 2025: GEUS Bulletin 62. 8401. https://doi.org/10.34194/5f80b592

Copyright: GEUS Bulletin (eISSN: 2597-2154) is an open access, peer-reviewed journal published by the Geological Survey of Denmark and Greenland (GEUS). This article is distributed under a CC-BY 4.0 licence, permitting free redistribution, and reproduction for any purpose, even commercial, provided proper citation of the original work. Author(s) retain copyright.

Received: 13 Jun 2025; Re-submitted: 16 Sept 2025; Accepted: 24 Oct 2025; Published: 23 Jan 2026

Competing interests and funding: This study was supported by the Denmark’s national budget (‘finansloven’).

*Correspondence: juliu@geus.dk; rs@geus.dk

Keywords: operational flood forecasting, flood warning, integrated groundwater–surface water modelling, National Hydrological Model, rising groundwater levels

Abbreviations:

DMI: Danish Meteorological Institute

ML: machine learning

ECMWF: European Centre for Medium-Range Weather Forecasts

LSTM: Long Short-Term Memory

SQL: Structured Query Language

RMSE: root-mean-square-error

Edited by: Rasmus R Frederiksen, Aarhus University, Denmark

Reviewed by: Robert J. Moore (UK Centre for Ecology & Hydrology), Bernhard Becker (Deltares, and RWTH Aachen University)

1 Introduction

Floods are amongst the most devastating natural disasters worldwide, causing substantial socio-economic damage (Tellman et al. 2021). Whilst fluvial and pluvial floods are well-recognised and have been investigated for decades due to their immediate and visible impacts (Merz et al. 2021), flooding caused by rising groundwater is often overlooked (Kreibich et al. 2009; Behzad & Nie 2024). Groundwater flooding is defined as surface inundation primarily originating from groundwater (Cobby et al. 2009). In the literature, the general term ‘high groundwater’ relates to a rise of groundwater level above normal that has adverse effects (Cobby et al. 2009; Becker et al. 2022). Groundwater flooding can occur after prolonged rainfall, high river stages or elevated sea levels, raising groundwater levels above normal and causing damage, often in low-lying areas or areas with specific soil and land-surface conditions (Becker et al. 2022; Parkin 2024). It can develop more gradually, often persisting for weeks or months and interacting dynamically with surface water systems, causing long-term damage – particularly to below-ground infrastructure such as basements, tunnels and sewer systems. The British Geological Survey estimates that groundwater flooding is responsible for approximately £530 million in damages annually in the United Kingdom, representing around 30% of the country’s total economic loss (Allocca et al. 2021).

Flood forecasting systems play a critical role in reducing the societal impacts of floods by supporting early warning, emergency planning and climate adaptation strategies (Cole et al. 2016; Adams et al. 2024). Many countries have developed national and regional forecasting frameworks, such as the National Water Prediction Service in the United States (NOAA 2016), the European Flood Awareness System (Smith et al. 2016), the Australian Flood Warning Services (Pagano et al. 2016) and the British Flood Alerts and Warnings (Moore & Bell 2002; Moore et al. 2006; Price et al. 2012; Cole et al. 2016). These systems vary in capabilities and tend to focus on surface water processes, with limited attention to integrated groundwater–surface water interactions. Such forecasts may underestimate the full extent and severity of a flood event without accounting for groundwater processes (e.g. low infiltration buffer in saturated soils and groundwater exfiltration). This is particularly problematic in low-lying areas or places with high water tables, where groundwater can emerge on the surface even without heavy surface runoff (Becker et al. 2022). Conventional surface water-focused systems often miss the slow-rising groundwater table. These events may not trigger standard warning thresholds, leading to delayed or absent alerts for communities vulnerable to prolonged flooding of basements, roads or critical infrastructure. Floods induced by rising groundwater levels can persist for longer, and emergency planning and allocation measures are inefficient when groundwater contributions are neglected in flood warning systems (Parkin 2024; Jüpner & Schüller 2025).

Denmark – where both surface water and groundwater flooding pose recurring risks – experiences considerable annual flood-related economic losses (Halsnæs et al. 2022). Responding to this need, we have developed a real-time, operational flood forecasting system that integrates both surface water and groundwater flooding processes. This system is designed to provide short-, medium- and long-term forecasts of fluvial and groundwater floods at a national scale. In this study, we present the development and initial performance of this integrated forecasting system under operational conditions. We carry out an initial event-based evaluation of its predictive capabilities with a focus on shallow groundwater dynamics, discuss limitations and explore future directions. By highlighting Denmark’s experience, this work aims to contribute to the global advancement of integrated flood forecasting and to offer guidance for similar initiatives in other countries that are exposed to groundwater flood risk.

2 Overview of the forecasting system

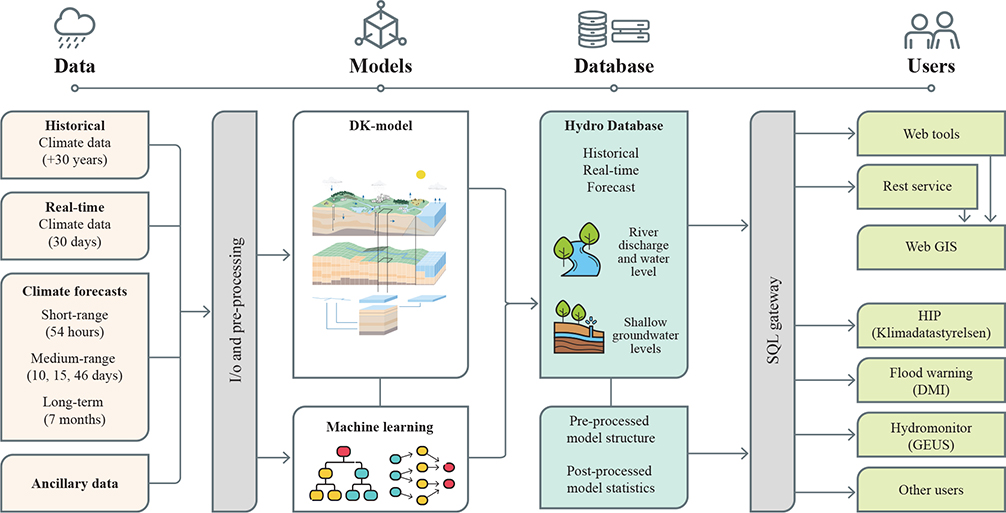

The flood forecasting system is an operational groundwater–surface water modelling system that integrates hydrometric observations (to gauge meteorological data, river flow and groundwater level), weather forecast downloading and preprocessing with pre-trained forecasting models, such as physically based hydrological and machine learning (ML) models and data management. The overall architecture of the forecasting system is illustrated in Fig. 1. The process begins with downloading various near real-time hydrometric observations and forecasted weather data from meteorological sources, which are then processed to the input formats required by the hydrological forecasting models. The models are then updated and run to predict water dynamics. Upon completion, the flood-relevant variables (discharge, depth to phreatic surface, etc.) are delivered to a database for data management, which serves as the backend for web viewers and platform for sharing. The system is implemented in Python for data preparation and post-processing of results, whilst the physically based hydrological model is developed within the MIKE software framework. The following sub-sections provide detailed descriptions of these components.

Fig. 1 Process flowchart of the flood forecasting system.

2.1 Climate data

The climate forcings, including precipitation, air temperature and potential evapotranspiration, used in the system consist of both observational data and weather forecasts. Observation-based historical and real-time climate data are sourced from national-gridded datasets provided by the Danish Meteorological Institute (DMI). These datasets, available at daily resolution, extend back to 1989 (Frie Data 2025; Scharling 1999a, b). Real-time data are available via the DMI Open Data API (Frie Data 2025). The observation data are sourced from a network of in situ weather stations distributed throughout Denmark. Air temperature is measured at a height of 2 metres above ground, and potential evapotranspiration is estimated using a modified Makkink’s equation (Plauborg et al. 2002). Operational precipitation gauges are typically installed 1–1.5 metres above ground level and are subject to wind-induced turbulence, which causes a systematic undercatch of precipitation. To correct for this bias, an empirical correction is dynamically applied based on rainfall intensity, wind speed and temperature, distinguishing between solid and liquid precipitation (Allerup et al. 1997; Stisen et al. 2011, 2012).

Climate forecasts used in the system are sourced from two providers: DMI’s Weather Model HARMONIE for Denmark, Iceland, the Netherlands and Ireland (DMI 2025) and the European Centre for Medium-Range Weather Forecasts (ECMWF; Palmer et al. 1990). The HARMONIE model delivers local high-resolution short-term forecasts with a lead time of up to 56 hours (h). ECMWF provides a suite of forecasts at various temporal scales: medium-range forecasts with lead times of 10 to 15 days, extended-range forecasts up to 46 days and long-range seasonal forecasts extending up to 7 months. These forecasts support both short- and long-term hydrological modelling and facilitate flood risk assessments.

2.2 Forecast models

The forecasting system uses two types of models: the physically based National Hydrological Model (DK-model) and data-driven ML models. The DK-model is an integrated groundwater–surface water model that covers most of Denmark’s land area (approximately 43 000 km²) and has been under continuous development for almost three decades (Højberg et al. 2013; Henriksen et al. 2021, 2023; Koch et al. 2021; Schneider et al. 2022). It is implemented in the MIKE SHE modelling framework (Abbott et al. 1986; DHI 2025), which fully couples a finite-difference 3D subsurface flow model with 2D overland flow, a simplified two-layer representation of the unsaturated zone and 1D kinematic river flow routing. The model has been calibrated for the period 2000 to 2010 using 304 daily river flow time series and groundwater head observations from approximately 40 000 wells across the country, with a focus on shallow groundwater and river flow in the version (Henriksen et al. 2020) used as part of the forecasting system.

ML models have demonstrated promising potential for flood forecasting (Nearing et al. 2024). To enhance both accuracy and computational speed of discharge predictions, we developed a hybrid ML post-processing model based on Long Short-Term Memory (LSTM) neural networks (Liu et al. 2024). Trained on historical data, this model incorporates real-time climate information and DK-model simulations to generate 10-day discharge forecasts, taking into account weather predictions during the forecasting period. The current ML system provides discharge forecasts for approximately 3000 catchment outlets across Denmark (Liu et al. 2025). A similar ML post-processing model for groundwater-level forecasting is under development.

2.3 Data management

Operationally, the models begin with real-time simulations that incorporate a 30-day look-back period for warm-up each day. These simulations provide the most up-to-date estimates of shallow groundwater levels and discharges, ensuring comparability with historical runs (also archived in the database) in terms of climate forcings and model configurations. The 30-day look-back period is set primarily to ensure the incorporation of quality-assured climate inputs, which can be updated with delay. Initial conditions for the groundwater system, unsaturated zone and river network are incorporated with a continuously updated hot-start process, using conditions from previous model runs. The real-time simulations are not only submitted to the database but also serve as initial conditions for forecast runs.

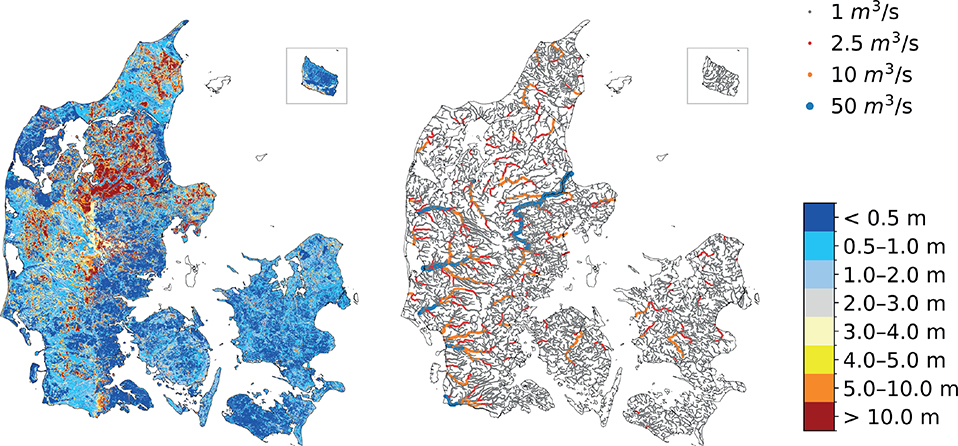

The forecasts start after real-time simulations. Short-range forecasts (54 h) and medium-range forecasts (10, 15 and 46 days) are generated once per day. Long-term forecasts (up to 7 months) are produced monthly and will be available at the start of each month but depend on the availability of ECMWF monthly weather forecasts. The medium-range forecasts use ensemble modelling with 51 ensemble members. All simulations provide river flow estimates for up to 60 000 river points as well as shallow groundwater levels (represented by depth to the phreatic surface) at 100 m and 500 m resolutions (see examples in Fig. 2). Short-range and 10-day ahead deterministic forecasts are available, whilst operational forecasts with ensembles and long-term forecasts are under development.

Fig. 2 Example of forecasted shallow groundwater depth (left) and discharge (right) on 23 January 2025. Shallow groundwater levels are presented as a raster map at 100 m resolution. The system also provides discharge forecasts at 62 728 points (from the 100 m model, shown as coloured dots with colour and size indicating discharge values) along nearly all river channels in Denmark. The up-to-date forecasts are available via Hydromonitor (https://data.geus.dk/hydromonitor/).

Once the real-time simulations and forecasts are completed, the results are uploaded to a centralised database called HydroDB, which supports data storage, statistical analysis, visualisation and user sharing. HydroDB stores historical simulations spanning 30 years (including river discharge and depth-to-top phreatic surface with additional data available upon request), updated annually to reflect newly available data. Real-time simulations and forecast outputs are updated daily and backed up for around one year. The model structure data, such as river network, geological and calculation layers, are stored in the database. Using historical records, along with the most recent real-time and forecast data, statistical analyses are conducted to assess current and forecasted conditions relative to historical baselines (e.g. how wet or dry a period is). Access to HydroDB data is provided through a Stru1ctured Query Language (SQL) gateway, for which users may apply for individual accounts. Example applications of this service include Hydromonitor (https://data.geus.dk/hydromonitor/) and the Hydrological Information and Prognosis System (HIP, https://hipdata.dk/).

2.4 Performance and case application

2.4.1 Accuracy of groundwater-level forecasts

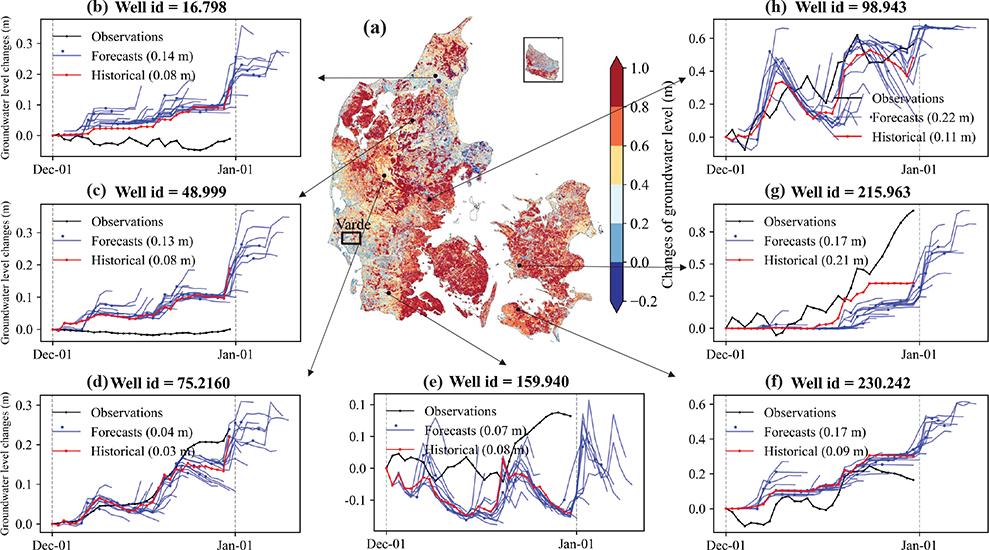

The forecasting system has been operational since October 2024, providing 10-day ahead forecasts of shallow groundwater levels and river discharge based on ECMWF’s 10-day weather forecasts. Figure 3a shows daily changes in groundwater level over the period 15 October 2024 to 9 January 2025. On average, groundwater levels increased by 1.70 metres across Denmark during this period with the spatial variation indicated in Fig. 3a. We initially evaluated the relative groundwater forecasts by comparing them with measurements from seven randomly distributed wells in Denmark (Figs 3b–h). The subplots in Fig. 3 display the 10-day groundwater-level forecasts alongside observed measurements relative to the groundwater levels on 1 December 2024. Overall, the simulated relative groundwater dynamics align well with the observations. The root-mean-square-error (RMSE) between observations and 5-day ahead forecasts (marked by red points in the subplots) ranges from 0.04 to 0.22 metres amongst the seven wells during the month, which is slightly higher than the accuracy of historical simulations, which are forced by observed climate data. Discrepancies persist in absolute groundwater levels, suggesting that further model improvement or post-processing is necessary.

Fig. 3 Comparison of relative groundwater-level forecasts (forced by ECMWF 10-day deterministic weather forecasts), historical simulations (forced by observed climate data) and measurements at seven wells from 1 December 2024 to 1 January 2025. Subplot (a) maps the differences between 15 October 2024 and 9 January 2025. Subplots (b–h) show the time series of groundwater-level forecasts (blue curves), where the forecasted groundwater levels at a lead time of 5 days are marked with blue dots (the RMSE refers to those), historical simulations (red curves) and measurements (dotted black curves).

2.4.2 Case study application

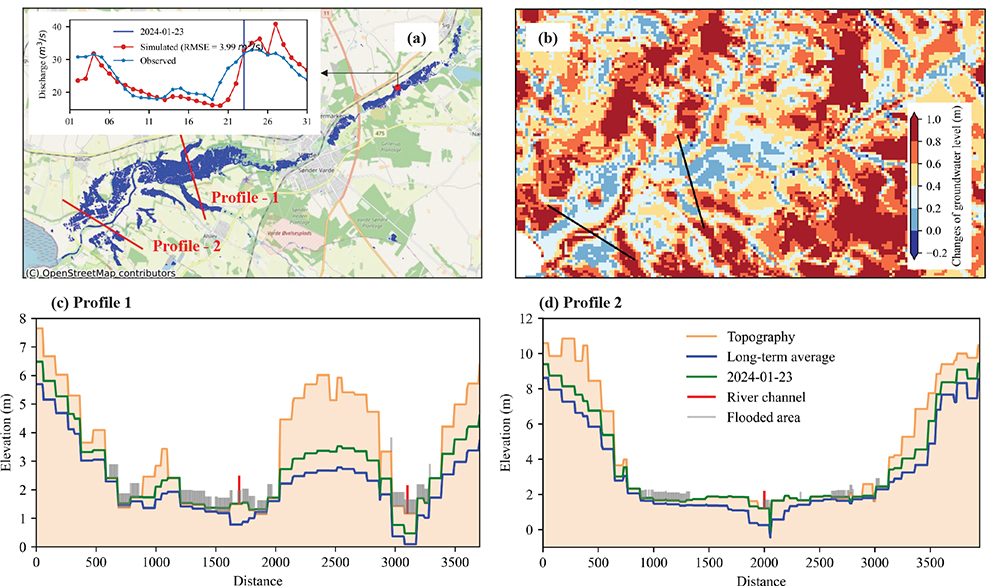

The DK-model is developed with moderate spatial resolution (up to 100 m), allowing flood forecasting across scales whilst at the same time being computationally manageable. To demonstrate its capabilities for local applications, we present a flood event that occurred downstream of the Varde River in mid-western Jylland on 23 January 2024 (see the location in Fig. 3a). The Varde River was chosen as the case study because the extent of the flooding was clearly captured by Sentinel-1 satellite imagery (Fig. 4a), revealing significant inundation across the region (Hansen et al. 2025). River discharge increased from 17.81 m³/s on 19 January to 31.92 m³/s on 23 January (Fig. 4a). The DK-model successfully captured this flood event at the river section, with simulated discharge increasing from 16.07 to 32.47 m³/s. The RMSE of the simulated discharge is 3.99 m³/s for January 2024 compared to observations, demonstrating the system’s promising capability for river flood forecasting.

Fig. 4 Application of the flood forecasting system to a local case study (Varde River). (a) Inundation extent derived from satellite imagery on 23 January 2024, and a comparison of simulated and observed discharge at the hydrological station during January 2024. (b) Relative changes of the groundwater levels on the same date compared to historical reference (mean values of 1989–2023) for the area. (c) and (d) are vertical profiles along two cross-sections across the river valley. The curves show model topography, groundwater level dated 23 January 2024 (green) and groundwater level from historical reference (blue). Flooded area from satellite data is indicated in grey and river location in red. Note that the real water surface elevation is unknown, so the grey and red bars in (c) and (d) do not indicate water depth of the inundated area but the locations.

No groundwater-well measurements were available in this region at the time. Therefore, we compared the simulated groundwater-level dynamics during the flood event to historical averages (1989–2023) to illustrate groundwater behaviour during the flood events. As shown in Fig. 4b, groundwater levels are elevated beyond the historical averages across most of the area. Even in the river valley, where groundwater is typically close to the surface, levels were elevated by 0.2–0.4 m compared to the historical baseline.

Figures 4c and d present two profiles showing model topography, groundwater levels, flooded areas along the profiles and the location of the main river channels. These profiles further confirm that during the event, groundwater levels were consistently higher than the historical averages. Flooding not only is concentrated along the river channel but also extends across the adjacent plains, as indicated by the grey vertical lines representing flooded locations. On profile 2, we see high groundwater levels without inundation left of the river. Such knowledge completes the picture of the expected flooding as such areas have a very low infiltration capacity so additional rainfall cannot be buffered. Notably, the simulated groundwater levels exceed the surface topography in some sections of the profiles, corresponding well with the observed inundation.

3 Short perspectives

In groundwater-dominated regions such as Denmark, the integration of groundwater into a forecasting framework enables the prediction of groundwater-level rise and groundwater flooding, a regularly occurring but often overlooked hazard (Parkin 2024). Additionally, the explicit representation of slower-reacting delayed groundwater processes enhances river flow forecasts from rainfall-runoff type models (as e.g. shown by Liu et al. 2024). The Danish integrated system developed across a range of institutions can serve as a reference for other countries facing similar hydrological hazards.

The flood forecasting system produces multiple hydrological forecasts each day, and the choice of output variables depends on the requirements of the end users. Initially, we provide absolute groundwater levels and river discharge, as these are the most direct indicators of potential flooding. We recommend using a combination of absolute groundwater levels and groundwater levels relative to historical reference values, as the DK-model has demonstrated high rates of forecast skill to accurately reproduce groundwater anomalies (Schneider et al. 2025; Seidenfaden et al. 2025). In addition, statistical indicators such as exceedance probabilities or return periods can provide valuable complementary information, offering a robust basis for assessing flood hazards.

Ongoing and future developments of the system aim to further increase forecast skill and expand lead time, including the integration of ensemble and seasonal weather forecasts. We are also paying special attention to improving the accuracy of absolute groundwater level predictions by, amongst other activities, developing Deep Learning post-processors to enhance groundwater-level predictions, which are comparable to the already applied post-processing of river flow simulations (Liu et al. 2024). Nevertheless, groundwater levels, when expressed relative to quantiles or return-period threshold levels, provide relevant information on impact severity (using rarity as a surrogate), and such statistical indicators are more robustly simulated than absolute levels (Seidenfaden et al. 2025). Finally, derived local scale models are envisaged for particularly vulnerable areas, especially urban areas at risk of being affected by compound events of flooding from rivers, sea and groundwater (Seidenfaden et al. 2025).

4 Conclusions

This study presented the ongoing development of a national-scale operational flood forecasting system for Denmark that explicitly integrates hydrological processes for surface water and groundwater. Groundwater flooding is often neglected in operational flood forecasting; hence, its inclusion represents a significant advancement. This work highlights that with appropriate data, modelling infrastructure and institutional collaboration, it is feasible to implement such integrated systems at a national scale – ultimately improving preparedness and resilience to a broader range of flood hazards.

Acknowledgements

This work was conducted as part of the Danish flood warning system from 2023 to 2026. The project is being led by the DMI in cooperation with the Geological Survey of Denmark and Greenland (GEUS), the Danish Agency for Climate Data (KDS), the Danish Environmental Protection Agency (MST), the Danish Coastal Authority (KDI) and the Danish Environmental Portal (DMP). We acknowledge the participants of the project and everyone involved in the development of the Danish National Hydrological Model (DK-model) at GEUS.

Additional information

Author contributions

Writing – Original Draft: Jun Liu, Raphael J.M. Schneider

Writing – Review & Editing: Julian Koch, Raphael J.M. Schneider, Simon Stisen, Lars Troldborg

Conceptualisation: Raphael J.M. Schneider; Julian Koch

Project Administration: Lars Troldborg

Competing interests

The authors declare no competing interest.