|

RESEARCH ARTICLE  |

A multidisciplinary biostratigraphic framework for the Lower to Middle Miocene of the Norwegian North Sea – the siliceous succession of the Valhall–Hod area

Abstract

A new multidisciplinary biostratigraphic framework, combining dinoflagellate cysts, microfossils, calcareous nannofossils, diatoms and silicoflagellates, is established for the Early to Middle Miocene deep marine clay and siliceous ooze in the southern Norwegian sector of the North Sea, based on core samples from the Valhall and Hod hydrocarbon fields. The framework was successfully tested on the equivalent chronostratigraphic level of several wells based on ditch cutting samples. New biostratigraphic events for the Danish and Norwegian North Sea resulting from this study are successfully used to correlate between the Valhall and Hod areas and supplement published zonation schemes. To our knowledge, this is the first time that diatoms and silicoflagellates from the fine fraction of microfossil samples have been used as correlation tools in the North Sea Basin. Dating of the siliceous/diatomite-rich interval results in a high-resolution (5–15 m intervals) biostratigraphic subdivision. The successful application of the new framework across the Valhall and Hod areas implies that it could also be useful in a more regional context. The new biostratigraphy enables the correlation of the lithostratigraphic units recently defined for the Danish offshore Neogene succession to the study area and the correlation of the sequence stratigraphic surfaces defined for the Danish sector to the southern Norwegian sector.

Citation: Sheldon et al. 2025: GEUS Bulletin 59. 8381. https://doi.org/10.34194/5k9dv133

Copyright: GEUS Bulletin (eISSN: 2597-2154) is an open access, peer-reviewed journal published by the Geological Survey of Denmark and Greenland (GEUS). This article is distributed under a CC-BY 4.0 licence, permitting free redistribution, and reproduction for any purpose, even commercial, provided proper citation of the original work. Author(s) retain copyright.

Received: 21 Aug 2024; Revised: 07 May 2025; Accepted: 11 Jun 2025; Published: 19 Dec 2025

Competing interests and funding: The authors declare no competing interests.

Aker BP and Pandion Energy funded this study.

*Correspondence: es@geus.dk

Keywords: biostratigraphy, diatomite, Miocene, North Sea, Norway

Abbreviations:

FO: first occurence

FSST: falling stage systems tract

GEUS: Geological Survey of Denmark and Greenland

HST: highstand systems tract

LO: last occurence

LST: lowstand systems tract

TST: transgressive systems tract

MMCT: Middle Miocene Climatic Transition

MCO: Miocene Climatic Optimum

PRZ: partial range zone

Edited by: Mette Olivarius (GEUS, Denmark)

Reviewed by: Haydon Bailey (Independent Researcher, UK), Erik Anthonissen (Equinor ASA, Norway)

1. Introduction

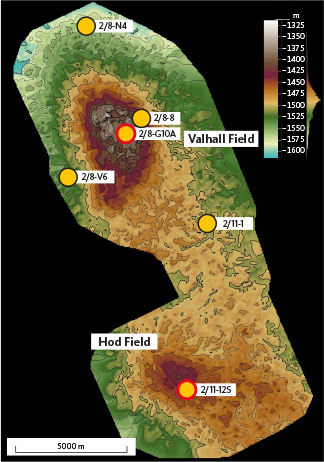

A new, multidisciplinary biostratigraphic study of the Lower and Middle Miocene sections of six wells from the Valhall and Hod fields is presented. These Upper Cretaceous – Danian chalk hydrocarbon fields are located on salt structures in the southernmost part of the Norwegian North Sea (Fig. 1). The Miocene succession above the chalk comprises deep-marine clay with a variable content of siliceous ooze. The silica content reaches 50% in some intervals, which are often referred to as diatomite. The focus is on the siliceous ooze or diatomite in some areas, such as the Valhall–Hod area, because of its hydrocarbon reservoir potential and because its geomechanical properties are critical in connection with well abandonment.

Fig. 1 Palaeogeography of the North Sea area in the Early Miocene. The red dot indicates the location of the study area. Arrows indicate sediment influx. The Valhall/Hod area was located in the central part of the basin. North Sea sectors are as follows: D: Germany. DK: Denmark. N: Norway. NL: Netherlands. UK: United Kingdom. Modified from Rasmussen et al. (2008).

Two of the six studied well sections, 2/11–12S (Hod Field) and 2/8–G10A (Valhall Field), were cored through the Lower and Middle Miocene successions, providing an exceptional and continuous record, unique in the North Sea area. The other four studied wells, 2/8–N4, 2/8–V6, 2/8–8 (all from Valhall Field) and 2/11–1 (in the saddle between the Valhall and Hod fields), were not cored. The locations of the wells are shown in Fig. 2.

Fig. 2 Depth map to the top Miocene of the Valhall and Hod structures and locations of the six studied wells (yellow dots). Wells circled in red are cored. Credit: Aker BP.

The purpose of this study is to establish a high-resolution multidisciplinary biostratigraphy for the siliceous or diatomite-rich succession represented by the unique Hod and Valhall cores. The resulting biostratigraphic framework is then applied to the four non-cored wells using fossil assemblages from ditch cutting samples.

The study was performed combining five biostratigraphic groups: dinoflagellate cysts (dinocysts), microfossils (primarily foraminifera but also including large diatoms and Bolboforma), small fraction diatoms, silicoflagellates and calcareous nannofossils, mostly on the same series of closely spaced sediment samples. This is the first time, to our knowledge, that a detailed North Sea Miocene biostratigraphic study includes small siliceous diatoms and silicoflagellates.

2. Geological setting and palaeoclimate

The Oligocene–Miocene transition was characterised by inversion tectonism resulting in shallower waters in the north-eastern part of the North Sea Basin (Ziegler 1990; Rasmussen 2009, 2013; Knox et al. 2010). The initial uplift of the Southern Scandes (Fig. 1) re-exposed the present-day Norway and central Sweden, which formed a low relief landscape at the end of the Oligocene (Thyberg et al. 2000; Løseth & Henriksen 2005; Gabrielsen et al. 2009). The uplift of the hinterland in the Early Miocene and the shallowing of the north-eastern North Sea Basin resulted in progradation of large delta systems from Scandinavia (Rasmussen et al. 2010; Fig. 1). In the northern North Sea Basin, delta progradation occurred from the west, the Shetland Platform, coincident with the eastern system (Eidvin et al. 2014a). The southern North Sea Basin was dominated by a coastal plain, and swamp environments formed the margin of a low-relief central European landscape, which was separated from the Alps by a foreland basin (Fig. 1).

During the Middle Miocene, a major transgression occurred, and the deltas established during the Early Miocene were flooded. The flooding commenced coincident with a global climatic deterioration (Zachos et al. 2001) and the initiation of a new tectonic regime in the North Atlantic. Huge inversion structures were formed off west Norway, and the main phase of uplift of the Sole Pit structure in the western part of the North Sea Basin took place (Knox et al. 2010; Løseth et al. 2017 and references therein). Iceland also formed at this time (Rasmussen et al. 2008), so branches of the Icelandic Plume (Schoonman et al. 2017) may also have reshaped the landscape around the northern North Sea Basin. The late Early Miocene to Middle Miocene was also an important phase in the uplift of the Carpathian Mountains in Central Europe (Oszczypko 2006). The establishment of the new tectonic regime resulted in accelerated subsidence of the North Sea Basin, and the deposition of marine mud dominated the Middle Miocene (Koch 1989; Rasmussen 2004a, 2004b; Rasmussen & Dybkjær 2014). Our study area was situated in a fully marine, outer shelf to upper bathyal, basin floor setting in a semi-closed basin with long distances to coastlines. Deposition was characterised by hemipelagic sedimentation in water depths of between 500 and 1000 m.

During the Late Miocene, continued growth of the Carpathian Mountains, uplift of the Alpine Foreland Basin and formation of the Jura Mountains resulted in the formation of a massive new source area in Central Europe (Kuhlemann 2007; Fig. 1).

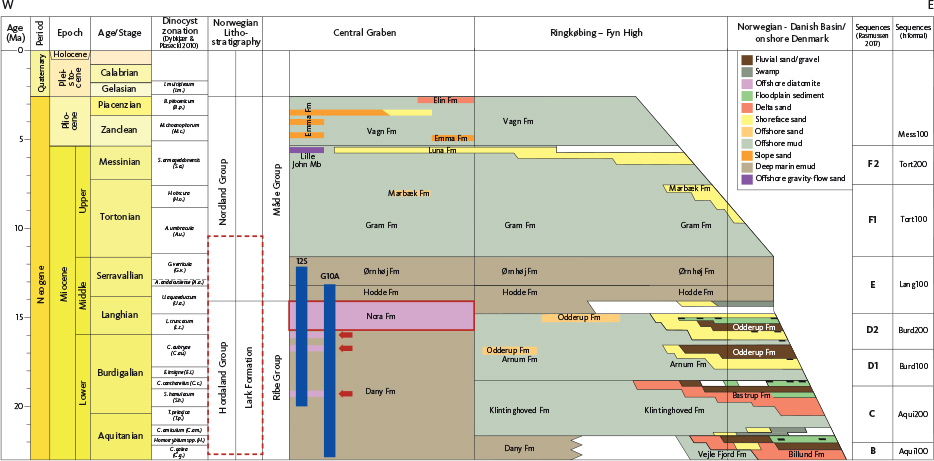

In the Late Miocene, huge, braided river systems supplied the south-eastern North Sea Basin for the first time (Knox et al. 2010). The new central European river system evolved into the so-called Eridanos Delta system (Biljsma 1981; Overeem et al. 2001; Rasmussen & Dybkjær 2014), which began to fill the eastern North Sea Basin. Delta systems sourced from Scandinavia also began to prograde into the north-eastern part of the basin during the latest Late Miocene and reached the Central Graben area during the Messinian Stage when they coalesced with the Eridanos Delta. These delta systems correlate with the Nordland Group of the Norwegian part of the North Sea (Fig. 3).

Fig. 3 The new lithostratigraphic subdivision for the Neogene succession in the Danish sector of the North Sea (modified from Rasmussen et al., in press) with a dashed red box showing the studied interval. Note the presence of diatomite in the middle Miocene, referred to as the Nora Formation (solid red box), and some minor occurrences in the Lower Miocene succession within the Dany Formation (red arrows). The intervals covered by the two cored well sections (2/11–12S and 2/8–G10A) are shown. The timescale of Raffi et al. (2020) is used in this figure.

The climate in the study area was warm-temperate to sub-tropical and humid during the Early and Middle Miocene (Utescher et al. 2009; Larsson et al. 2011; Sliwinska et al. 2024). Studies on the Sdr. Vium borehole, Jylland, Denmark, by Larsson et al. (2011), Herbert et al. (2020) and Sliwinska et al. (2024) indicate mean annual temperatures of around 17–18.5°C on land, mean annual precipitation of c. 750–1750 mm/yr and sea surface temperatures of 23–28°C, although with some fluctuations during the Miocene Climatic Optimum (MCO) (c.17–13 Ma; e.g. Larsson et al. 2011; Herbert et al. 2020; Sliwinska et al. 2024).

At the end of the Middle Miocene, the global climate deteriorated, a period known as the Middle Miocene Climatic Transition (MMCT). In the Danish and German areas, a decrease in annual temperatures during the Serravalian Stage has been recognised (Utescher et al. 2009; Herbert et al. 2020, Sliwinska et al. 2024). Marked climatic deterioration in the Messinian Stage at the close of the Miocene Epoch resulted in the expansion of ice caps on Antarctica and probably also in parts of the northern hemisphere (Utescher et al. 2009).

3. Lithostratigraphy

The Neogene deposits in the North Sea area include marginal, fluvio-deltaic deposits, shoreface and offshore shelf deposits and basinal deep water hemipelagic and gravity-flow deposits. Silica- or diatomite-rich deposits are found locally in basinal areas (including the study area) in the Lower and Middle Miocene parts of the succession. A new lithostratigraphic subdivision of the Neogene succession in the Danish North Sea sector is presented in Rasmussen et al. (in press; modified version presented here, Fig. 3). In this study, we correlate the new offshore Danish lithostratigraphy to the Norwegian sector of the North Sea. This lithostratigraphy includes the new Lower Miocene Dany Formation, which comprises muddy and silty deposits, and the new Middle Miocene Nora Formation, which is defined based on its high content of silica or diatomite. The well sections presented in this study include the Dany, Nora and Hodde formations following the new subdivision. According to the Norwegian lithostratigraphy for the Late Paleocene to Neogene, the studied Lower and Middle Miocene succession is subdivided into the Hordaland Group (Lark Formation) and the Nordland Group (Eidvin et al. 2022; Fig. 3). In this study, lithostratigraphic information including diatomite content is available for the two cored wells 2/8–G10A and 2/11–12S, and thus, it has been possible to subdivide the Miocene succession into the lithostratigraphic units defined in the Danish sector. An attempt at a similar subdivision in the non-cored wells is made, based on gamma log responses.

4. Sequence stratigraphic framework

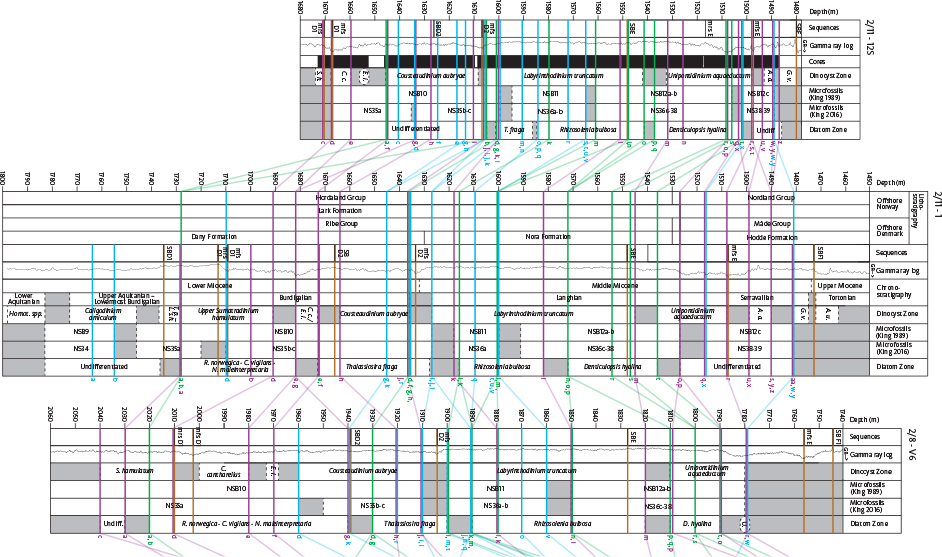

In the Danish and southern Norwegian sectors, eight depositional sequence boundaries are found within the Miocene succession (Rasmussen et al. 1996, Rasmussen 2004b, 2017). The boundaries are defined on a combination of studies of outcrop sections onshore Denmark, borehole logs and cores and seismic data, including high-resolution shallow seismic, multichannel, and for the Central Graben area, 3D seismic data (Rasmussen 1996; Rasmussen 2004b, 2017, Dybkjær et al. 2021). The eight sequence boundaries confine seven fully developed sequences, named B, C, D1, D2, E, F1 and F2 (Rasmussen 2004b, 2017). The two lowermost sequences, B and C, and the F2 sequence include all four systems tracts (LST: lowstand systems tract, TST: transgressive systems tract, HST: highstand systems tract and FSST: falling stage systems tract), whereas the upper Lower Miocene to lower Upper Miocene sequences only have a two-fold subdivision (TST and HST). The latter was due to increased subsidence of the North Sea Basin during the middle part of the Miocene outpacing eustatic sea-level fall (Rasmussen 2004b, 2017). The seismic surfaces can be seen for the 2/8–G10A and 2/11–125 wells in Figs 5 and 6 and for all wells in the Supplementary Files S1–S12.

5. Absolute dating

Absolute dating by palaeomagnetic stratigraphy, radiometric dating or Sr isotope stratigraphy of the Miocene succession in the North Sea Basin is rare. Deeper levels were usually targeted for hydrocarbon exploration, while the younger ‘overburden’ was traditionally considered uninteresting and therefore only rarely cored.

Therefore, the absolute ages of dinocyst and microfossil events within the Miocene succession in the North Sea Basin as shown by Powell (1992), Munsterman & Brinkhuis (2004), Louwye et al. (2007), Dybkjær & Piasecki (2010), Köthe (2012), King (1989, 2016), Munsterman et al. (2019) and Dybkjær et al. (2019) are usually based on data from areas outside the North Sea Basin, where these events are found in wells where absolute dating has been carried out (e.g. Haq et al. 1987; De Verteuil & Norris 1996; De Verteuil 1997; Williams et al. 2004 and references therein). Also, correlation with other microfossil groups (e.g. nannofossils) and the global sea-level changes have been used to date the dinocyst and microfossil events recorded in the North Sea Basin (e.g. Dybkjær & Piasecki 2010; King 2016; Munsterman et al. 2019). However, the absolute dating of specific events varies from one reference to another, due to the diachronicity of first and last appearance datums and uncertainties of the datings.

The most comprehensive Sr-isotope study of the Miocene North Sea Basin is that of Eidvin et al. (2014b) from onshore Denmark. The results of that study generally supported the ages of the dinocyst zones of Dybkjær & Piasecki (2010) in the Early Miocene but also documented the uncertainty of using Sr-isotopes for dating this stratigraphic level, especially the late Middle to Late Miocene part of the succession.

Comparing the dinocyst event and zonation scheme of Dybkjær & Piasecki (2010, their fig. 6) with that of King (2016, their fig. 18) clearly reflects this uncertainty in chronostratigraphic correlation. Similarly, correlation between dinocyst and microfossil events and zones also differs in the two publications (e.g. Dybkjær & Piasecki 2010, their fig. 6; King 2016, their fig. 21). Correlation between Miocene nannofossil and microfossil zones is also problematic, as seen in and explained by King (2016), compare their figs. 21 and 27.

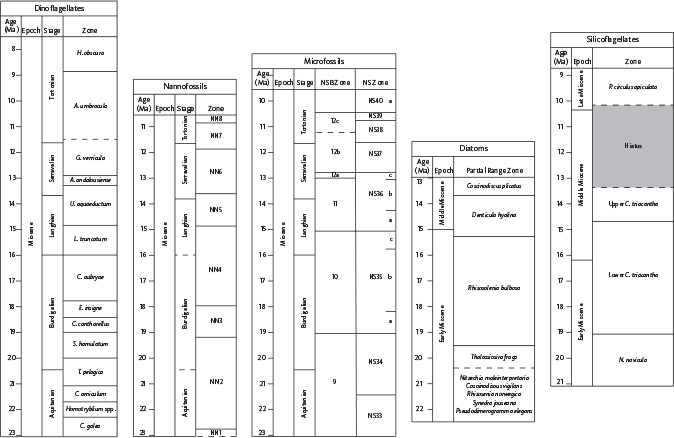

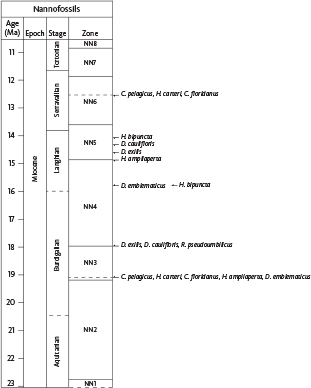

Absolute dating has not been carried out on the studied wells. Due to this absence of an absolute age model, the events and biozonations for the five studied microfossil groups are presented against established zonations (Fig. 4), sample depth, sequence boundaries, lithostratigraphy and the gamma log, instead of against a timescale (Ma), see Figs 5, 6 and Supplementary Files S1–S12.

Fig. 4 Biostratigraphic zonations used in this study. Dinocyst zonation of Dybkjær & Piasecki (2010), nannofossil zonation of Martini (1971), microfossil zonations of King (1989, 2016), diatom zonation of Schrader & Fenner (1976) & the silicoflagellate zonation of Locker & Martini (1989). Refer to individual references for timescales applied.

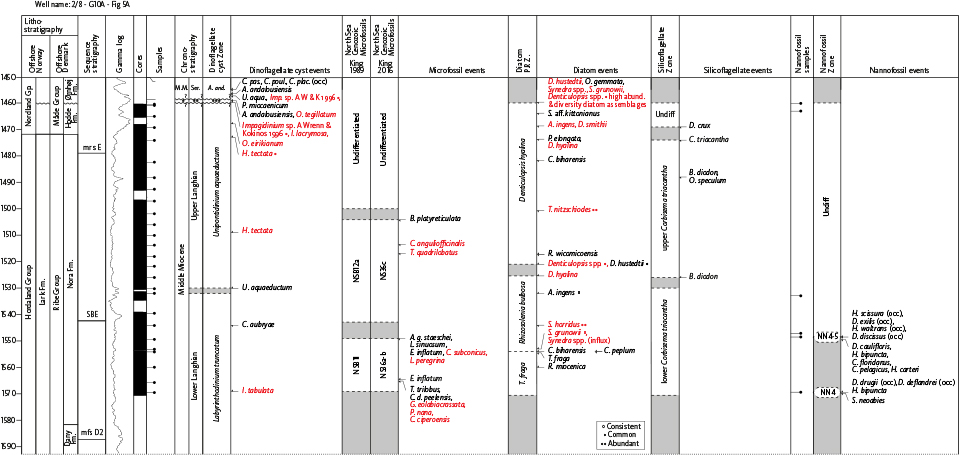

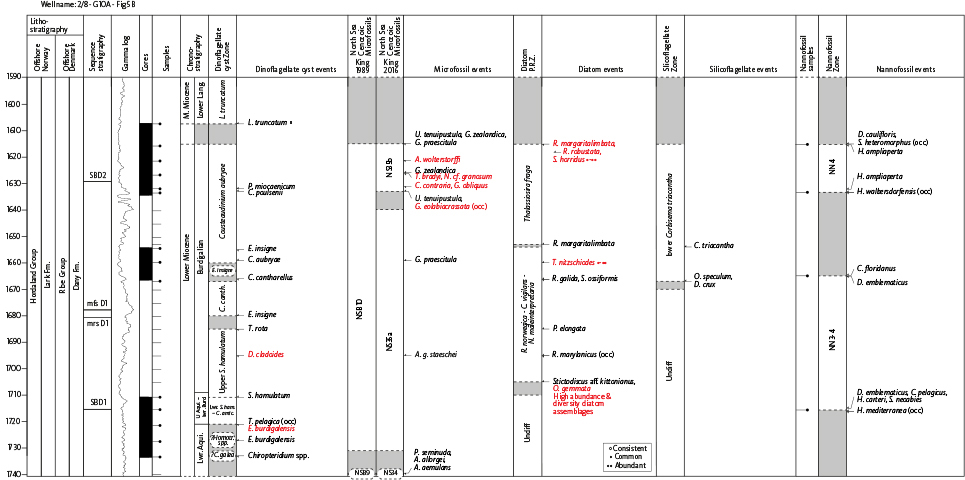

Fig. 5 Summary diagram for the 2/8–G10A well with biostratigraphic zones, previously published events (black text) and new events (red text), for full fossil names see Supplementary File S1. Lithostratigraphy for the Norwegian Sector from Eidvin et al. (2022), onshore Denmark from Rasmussen et al. (2010) and offshore Denmark from Rasmussen et al. (in press). Sequence stratigraphy from Rasmussen (2004a; 2017) and Dybkjær et al. (2021). Gamma log c/o Aker BP. Cored intervals are indicated. The main sample column indicates samples for dinocysts, microfossils, diatoms and silicoflagellates. Nannofossil samples are indicated separately. In the ‘Cores’ column, core samples are marked with a dash-dot symbol, and ditch cutting samples are marked with a dash. Chronostratigraphy of Raffi et al. (2020), dinocyst zonation of Dybkjær and Piasecki (2010), microfossil zonations of King (1989; 2016), diatom zonation of Schrader and Fenner (1976), silicoflagellate zonation of Locker and Martini (1989) and nannofossil zonation of Martini (1971). *: Late Miocene, **: late Tortonian, ***: Hystrichosphaeropsis obscura zone. FM: Formation. M.M. and M. Micoene: Middle Miocene. Ser.: Serravallian. Lang.: Langhian. P.R.Z.: Partial Range Zone. U.: Upper. Lwr.: Lower. Aqui.: Aquitanian. Burd.: Burdigalian. Undiff.: Undifferentiated.

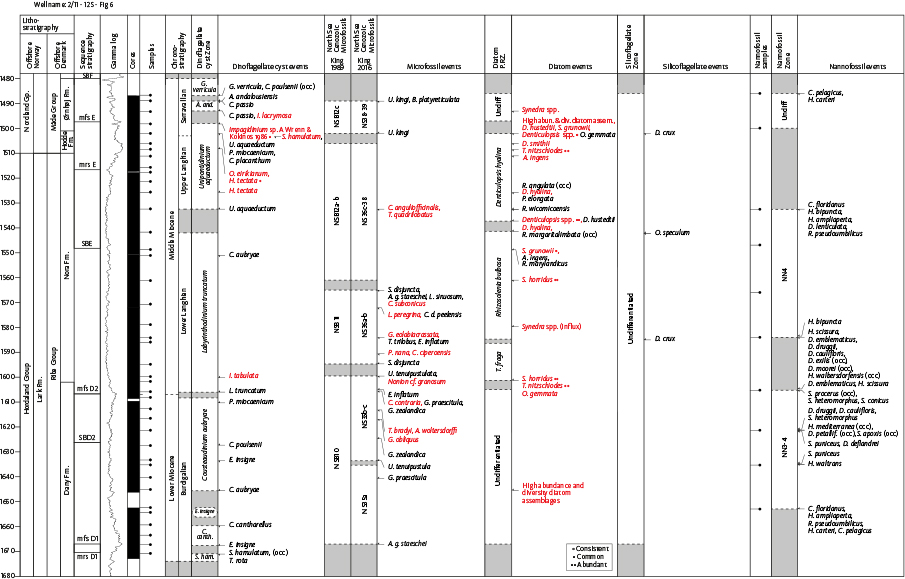

Fig. 6 Summary diagram for the 2/11–12S well with biostratigraphic zones, previously published events (black text) and new events (red text), for full fossil names see Supplementary File S2. Lithostratigraphy for the Norwegian Sector from Eidvin et al. (2022), onshore Denmark from Rasmussen et al. (2010) and offshore Denmark from Rasmussen et al. (in press). Sequence stratigraphy from Rasmussen (2004a; 2017) and Dybkjær et al. (2021). Gamma log c/o Aker BP. Cored intervals are indicated. The main sample column indicates samples for dinocysts, microfossils, diatoms and silicoflagellates. Nannofossil samples are indicated separately. Core samples are marked with a dash with a dot, and ditch cutting samples are marked with a dash. Chronostratigraphy of Raffi et al. (2020), dinocyst zonation of Dybkjær and Piasecki (2010), microfossil zonations of King (1989, 2016), diatom zonation of Schrader and Fenner (1976), silicoflagellate zonation of Locker and Martini (1989) and nannofossil zonation of Martini (1971). FM: Formation. Undiff.: Undifferentiated.

6. Previous studies

The majority of biostratigraphic work that has been carried out on the Neogene succession of the North Sea area over the past 50 years is a direct result of extensive hydrocarbon exploration at deeper levels.

Palynological studies on the Miocene succession in the North Sea include Piasecki (1980), Strauss & Lund (1992), Powell (1992), Head (1996), Louwye et al. (1999), Louwye (2002), Dybkjær & Rasmussen (2000, 2007), Strauss et al. (2001), De Schepper et al. (2004, 2009), Dybkjær (2004a, 2004b), Munsterman & Brinkhuis (2004), Schiøler (2005), Köthe & Piesker (2007), Louwye et al. (2007), Louwye & Laga (2008), Louwye & De Schepper (2010), Dybkjær & Piasecki (2010), Dybkjær et al. (2012), Köthe (2012), Eidvin et al. (2014a, 2014b), Śliwinska et al. (2014), King (2016), De Schepper & Mangerud (2017), Grøsfjeld et al. (2019), Dybkjær et al. (2021) & Sliwinska et al. (2024).

Microfossil studies of the Miocene of the North Sea area are also numerous (Von Daniels & Spiegler 1977; Doppert et al. 1979; Doppert 1980; Spiegler & Von Daniels 1991; Spiegler 1999; King 1983, 1989, 2016; Gradstein et al. 1988; Gradstein & Backstrom 1996; Laursen & Kristoffersen 1999; Eidvin et al. 1999; Kaminski & Gradstein 2005; Rundberg & Eidvin 2005; Eidvin & Rundberg 2007; Anthonissen 2012; Fox et al. 2018).

Published Neogene calcareous nannofossil studies for the North Sea area are not common due to the siliciclastic nature of much of the Neogene section and the successful application of high-resolution studies of other biostratigraphic disciplines. Neogene nannofossil studies of the broader North Atlantic region include Müller (1976), Steinmetz (1979), Gartner (1992), De Kaenel et al. (2017), Boesiger et al. (2017) and Bergen et al. (2017). The global nannofossil ‘NN’ zonation of Martini (1971) is still widely used and is correlated with other nannofossil zonations in Young et al. (1994) and Young (1998).

For the North Sea area, the use of diatoms for Palaeogene and Neogene biostratigraphy was studied by Mitlehner (2019). Several biostratigraphic studies of Upper Oligocene and Lower Miocene North Sea successions using large, pyritized diatoms in conjunction with other microfossils have also been published. King (1983, 2016) focused on the Cainozoic micropalaeontological biostratigraphy of the North Sea and adjacent areas. Laursen and Kristoffersen (1999) studied the Miocene successions of onshore Denmark using foraminifera, and Dybkjær et al. (2012) concentrated on the Oligocene–Miocene boundary in the eastern North Sea Basin using dinocyst stratigraphy, micropalaeontology and δ13C-isotope data. Eidvin and Rundberg (2001) focused on the Late Cainozoic stratigraphy of the northern North Sea, and Anthonissen (2012) compiled an integrated Miocene biostratigraphy for the northeastern North Atlantic.

Small siliceous diatoms are not generally used in the North Sea area for routine biostratigraphy as their minute size results in them being washed through standard sieves, and their delicate structures are easily destroyed by the harsh preparation techniques used in industry. A diatom zonation scheme for the North Sea does not exist. However, studies with potential use in biostratigraphy in the Neogene of the North Sea area include Eidvin et al. (1998), Thyberg et al. (1999) and Sheldon et al. (2018). Siliceous diatom studies from the wider high northern latitudes that are useful for correlation with this study include those of Schrader & Fenner (1976), Koç & Scherer (1996) and Suto (2006) from the Norwegian and Iceland Seas, Dzinoridze et al. (1979) from the Norwegian Basin and Baldauf (1985) from the Rockall Plateau.

Silicoflagellates only comprise a small percentage of the siliceous component of marine sediments and therefore have limited biostratigraphic use. A silicoflagellate zonation scheme for the North Sea does not exist. Martini & Muller (1976), Locker & Martini (1989), Ciesielski et al. (1989) and Amigo (1999) investigated Miocene successions in the Norwegian-Greenland Sea and the Iceland-Rockall Plateau areas to the north of the study area.

7. Zonation schemes in this study

The biostratigraphic zonations used in this study are the North Sea dinocyst zonation of Dybkjær & Piasecki (2010), the North Sea microfossil zonations of King (1989, 2016), the global calcareous nannoplankton zonation of Martini (1971), the Norwegian Sea diatom zonation of Schrader & Fenner (1976) and the Norwegian Sea silicoflagellate zonation of Locker & Martini (1989), Fig. 4. In their study of the Neogene of the Iceland Sea, Koç & Scherer (1996) revised the biostratigraphy of Schrader & Fenner (1976). In this study, however, we revert to the zonation of Schrader & Fenner (1976) due to the similarity of diatom assemblages therein with those from the Valhall–Hod area. The zonation schemes follow a chronostratigraphy that was current when the zonation was published. The North Sea dinocyst zonation of Dybkjær & Piasecki (2010) follows the chronostratigraphy of Lourens et al. (2004). The North Sea microfossil zonations of King (1989, 2016) follow the chronostratigraphy of Hilgen et al. (2012) in King (2016). The global calcareous nannoplankton zonation of Martini (1971) is correlated with the chronostratigraphy of Raffi et al. (2020). The Norwegian Sea diatom zonation of Schrader & Fenner (1976) follows the chronostratigraphy of Berggren (1972), and the Norwegian Sea silicoflagellate zonation of Locker & Martini (1989) follows the chronostratigraphy of Berggren et al. (1985). It is beyond the scope of this paper to attempt an up-to-date chronostratigraphic correlation of the five zonation schemes. Dinocyst taxonomy follows the ‘Lentin & Williams Index’ (Williams et al. 2017). Microfossil taxonomy follows that used in King (1989, 2016) and Young et al. (2024b). Nannofossil taxonomy is based on Young et al. (2024a). Diatom taxonomy follows that of Schrader & Fenner (1976) and Barron (1985), and silicoflagellate taxonomy follows that of Perch-Nielsen (1985) and Locker & Martini (1989).

8. Materials and methods

Cores from the 2/11–12S (Hod Field) and 2/8–G10A (Valhall Field) wells were sampled with a spacing of approximately 4 to 5 m. Ditch cutting samples were taken from the core gap in 2/8–G10A. For the non-cored wells 2/8–N4, 2/8–V6, 2/8–8 (all Valhall Field) and 2/11–1 (in the saddle between the Valhall and Hod fields), ditch cutting samples were taken every 10 m (Table 1). The position of the analysed samples in each well is shown in Figs 5, 6 and Supplementary Files S1–S12.

Most of the samples were analysed for palynology (dinocysts), microfossils (large fraction) and siliceous microfossils (small fraction: diatoms and silicoflagellates). Only around ten samples per well were selected from minor calcareous-rich intervals and analysed for nannofossils as they are not routinely used for biostratigraphy in the Miocene of the North Sea.

8.1. Preparation methods

The sample preparation methods for each biostratigraphic discipline are described below. All sediment samples were processed in the Stratigraphic Laboratory at the Geological Survey of Denmark and Greenland (GEUS).

8.1.1. Palynology

Approximately 20 g of sample was dried and crushed until all particles were <2 mm in size. Dissolution of carbonates was carried out using 1M HCl until bubbling ceased, followed by 5M HCl for 24 h. This was followed by treatment with a mild solution of citric acid heated to 70°C. The silicate fraction was dissolved using cold HF (40%) for a minimum of 6 days, followed by treatment with a mild solution of citric acid heated to 70°C. The acid treatment was followed by brief oxidation with concentrated HNO3 and KOH 5% and by heavy liquid separation with ZnBr (2.3 g/ml). Each step was followed by filtration through an 11 µm nylon net. A final filtration through a 20 µm nylon net was carried out before mounting the acid-resistant organic particles in glycerin jelly on glass slides. The dinocyst slides were examined using a Leica DM2000 normal light microscope at 400x and 1000x magnification. A minimum of 200 dinocysts were identified to species level. Finally, the slide used for counting and an additional slide were scanned to include rare dinocyst taxa.

8.1.2. Microfossils (large fraction)

Approximately 50 g of sample was boiled to disaggregate it, and a little washing-up liquid was added to help remove drilling mud. The sediment was washed through a 63 µm sieve and dried at 60°C. The residues were sieved into >250 µm, >100 µm and >63 µm fractions. The larger fractions were picked for microfossils (primarily foraminifera, but also large diatoms and Bolboforma), and the >63 µm fraction was scanned. The microfossils were examined using a Leica M205C microscope and semi-quantitative counting.

8.1.3. Calcareous Nannofossils

Nannofossil smear slides were prepared using the simple smear slide technique described in Bown & Young (1998). The prepared slides were examined using a Leica DM2500P light microscope under x1000 magnification with cross-polarised light. Several slide traverses were analysed, and simple presence–absence recording was undertaken.

8.1.4. Siliceous microfossils (small fraction)

The siliceous microfossil (small fraction) preparation method used in this study was developed at GEUS. Hydrogen peroxide was used to remove the organic material. The sample was then boiled for several hours and cooled, and then, a small amount of 10% HCl was added. The sample was then cleaned with distilled water and allowed to rest, several times over, for a few days. Microspheres were added and the mixture pipetted onto a glass coverslip and dried overnight. The coverslip was mounted onto a glass slide with Naphrax and heated on a hot plate to set. The prepared slides were examined using a Leica DM2500P light microscope under x1000 magnification. For the two cored wells, the whole of each slide was analysed, and all diatoms and silicoflagellates were counted. For the non-cored wells, the five ‘longest traverses’ of the circular slide were counted.

9. Results

High-quality biostratigraphic data were produced from the two cored wells, 2/11–12S and 2/8–G10A; in that cored material is not subjected to harsh mechanical and chemical processes that can destroy fossil assemblages. The data from the ditch cutting samples from the 2/8–N4, 2/8–V6, 2/8–8 and 2/11–1 wells and from the core gap in 2/8–G10A are also generally of good quality, although caved dinocysts and microfossils occur. Natural processes such as reworking and fluctuations in abundance and diversity of the dinocysts and microfossils due to climatic or palaeoenvironmental changes also influence the data.

The multidisciplinary biostratigraphic study of the Lower and Middle Miocene succession of the 2/8–G10A and 2/11–12S cored sections resulted in the successful application of established regional dinocyst and microfossil biozonations (Dybkjær & Piasecki 2010; King 1989, 2016) and the global nannofossil zonation of Martini (1971), in addition to the recognition of several new key bioevents that appear to have stratigraphic potential (Figs. 4–8, Supplementary Files S1, S2, S13). The biozones and new events identified in the cored wells were tested on the non-cored sections with a high degree of success and are discussed here (see also Fig. 8 and Supplementary Files S3–S13). To our knowledge, diatoms (small fraction) and silicoflagellates have not previously been applied to routine biostratigraphy in the North Sea and are therefore discussed in some detail here. FO denotes the first (oldest) stratigraphic occurrence in this study, and LO denotes the last (youngest) stratigraphic occurrence in this study. Established biostratigraphic events are indicated by black text in figures, and new events are indicated in red text in figures.

Fig. 7 Overview of the relative position of Early to Middle Miocene calcareous nannofossil events from the Valhall–Hod area. Nannofossil zonation of Martini (1971).

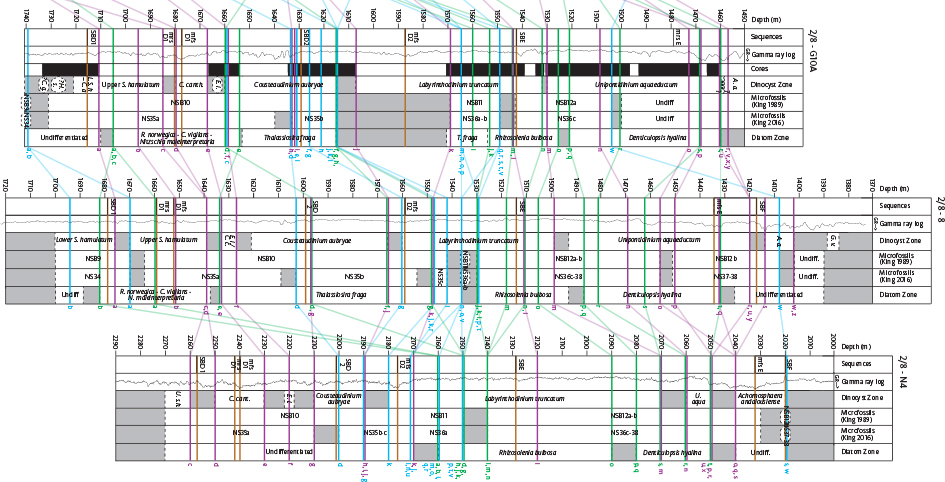

Fig. 8 Multidisciplinary biostratigraphic correlation diagram of the six studied wells, from south to north, from the Hod Field to the Valhall Field using dinocyst, microfossil and diatom events. Events are correlated using coloured correlation lines and are denoted using a letter as follows: Dinocysts (purple lines): a: FO Sumatradinium hamulatum, b: LO Dinopterygium cladoides, c: LO Thalassiophora rota, d: FO Exochosphaeridium insigne, e: LO Cordosphaeridium cantharellus, f: FO Cousteaudinium aubryae, g: LO Exochosphaeridium insigne, h: FO Cerebrocysta poulsenii, i: FO Palaeocystodinium miocaenicum, j: FO Labyrinthodinium truncatum, k: FO Invertocysta tabulata, l: LO Cousteaudinium aubryae, m: FO Unipontidinium aquaeductum, n: FO Habibacysta tectata, o: FO Habibacysta tectata (common), p: FO Operculodinium erikanium, q: LO Cleistosphaeridium placacanthum, r: LO Unipontidinium aquaeductum, s: LO Sumatradinium hamulatum, t: FO Impagidinium sp A Wrenn & Kokinos 1996 (common), u: FO Invertocysta lacrymosa, v: FO Cannosphaeropsis passio, w: LO Cannosphaeropsis passio, x: LO Palaeocystodinium miocaenicum, y: FO Achomosphaera andalousiensis, z: FO Grammocysta verricula, aa: FO Amiculosphaera umbracula. Microfossils (blue lines): a: LO Plectofrondicularia seminuda, b: LO Aulacodiscus allorgei, c: FO Globorotalia praescitula, d: FO Uvigerina tenuipustulata, e: LO Globigerinoides obliquus, f: FO Globorotalia zealandica, g: LO Trifarina bradyi, h: LO Alabamina wolterstorffi, i: LO Ceratobulimina contraria, j: LO Globorotalia zealandica, k: LO Globorotalia praescitula, l: LO Uvigerina tenuipustulata, m: LO Paragloborotalia nana, n: LO Ciperoella ciperoensis, o: LO Trilobatus trilobus, p: LO Globoturborotalita eolabiacrassata, q: LO Elphidium inflatum, r: LO Lenticulina peregrina, s: LO Cancris subconicus, t: LO Loxostomum sinuosum, u: LO Sphaeroidinellopsis disjuncta, v: LO Asterigerina guerichi staeschei, w: LO Bolboforma platyreticulata, x: FO Uvigerina kingi, y: LO Uvigerina kingi. Diatoms (green lines): a: FO High abundance and diversity diatom assemblages, b: FO Opephora gemmata, c: FO Stictodiscus aff. kittonianus, d: FO Thalassionema nitzschiodes (common to abundant), e: FO Raphoneis margaritalambata, f: LO Raphoneis margaritalambata, g: FO Stephanopyxis horridus (common to abundant), h: FO Raphoneis robustata, i: FO Rhizosolenia miocenca, j: FO Cymatosira biharensis, k: FO Synedra spp. (influx), l: FO Stephanopyxis grunowii, m: LO Stephanopyxis horridus (common to abundant), n: FO Actinocyclus ingens, o: FO Denticulopsis hyalina, p: FO Denticulopsis spp. (common to abundant), q: FO Denticulopsis hustedtii, r: LO Thalassionema nitzschiodes (common to abundant), s: LO Diploneis smithii, t: LO High abundance and diversity diatom assemblages (including A. ingens, Denticulopsis spp., O. gemmata, S. grunowii, S. aff. kittonianus, Synedra spp.). Sequence boundary correlations are marked in brown. The datum line for the correlation is sequence boundary SBE. Lithostratigraphy for the Norwegian Sector from Eidvin et al. (2022), onshore Denmark from Rasmussen et al. (2010) and offshore Denmark from Rasmussen et al. (in press). Sequences from Rasmussen (2004a; 2017) and Dybkjær et al. (2021). Gamma (GR) log c/o Aker BP. Cored intervals are indicated. Chronostratigraphy of Raffi et al. (2020), dinocyst zonation of Dybkjær & Piasecki (2010), microfossil zonations of King (1989, 2016) and diatom zonation of Schrader & Fenner (1976). Dinocyst zone abbreviations: A. a.: Achomosphaera andalousiensis, A. u.: Amiculosphaera umbracula, C. a.: Caligodinium amiculum, C. c.: Cordosphaeridium cantharellus, C. g.: Chiropteridium galea, E. i.: Exochosphaeridium insigne, G. v.: Gramocysta verricula, H. s.: Homotryblium spp., L. S. h.: Lower Sumatradinium hamulatum, S. h.: Sumatradinium hamulatum, T. p.: Thalassiphora pelagica, U. S. h.: Upper Sumatradinium hamulatum, ***: Hystrichosphaeropsis obscura, U.: undifferentiated. Grey shading denotes no information. A full-sized version of this figure is available as Supplementary File S13.

9.1. Palynology

In total, the studied succession from the six wells covers 14 of the dinocyst zones defined by Dybkjær & Piasecki (2010), comprising the Chiropteridium galea Zone (early Aquitanian) to the Hystrichosphaeropsis obscura Zone (late Tortonian; Figs 5, 6 and Supplementary Files S1–S6).

In the 2/11–12S core, eight dinocyst zones were recorded, spanning the early Burdigalian Sumatradinium hamulatum Zone to the Serravallian Gramocysta verricula Zone (Fig. 6).

The studied succession in the partly cored 2/8–G10A well starts somewhat lower, possibly in the early Aquitanian Chiropteridium galea Zone (Fig. 5). The palynostratigraphy of this lower part is not well defined, and the presence of the lower two zones, the C. galea Zone and the Homotryblium spp. Zone, are questionable as the index taxa occur in very low numbers and may be reworked. However, the occurrence of microfossil Zone NSB9 (King 1989) around this level supports an early Aquitanian age for this interval. The succession up to the Unipontidinium aquaeductum Zone seems to be complete. Above the U. aquaeductum Zone, three dinocyst zones, the Achomosphaera andalousiense Zone, Gramocysta verricula Zone and Amiculosphaera umbracula Zone, are missing corresponding to the upper part of the Serravallian and the lower part of the Tortonian succession. The U. aquaeductum Zone is overlain by an interval referred to as the late Tortonian Hystrichosphaeropsis obscura Zone. Above the H. obscura Zone is an interval referred to as the early Serravallian A. andalousiense Zone, indicating a repeated section possibly due to faulting.

9.2. Dinocyst events

In addition to the FOs and LOs defining zonal boundaries, Dybkjær & Piasecki (2010, their figs. 6, 7) also presented selected additional stratigraphically useful events in their zonation. These events were also found in this study, including the base of Ectosphaeropsis burdigalensis, the top of Thalassiphora rota, the base of Sumatradinium hamulatum, the top of Exochosphaeridium insigne, the base of Cerebrocysta poulsenii, the top of Cousteaudinium aubryae, the base of Palaeocystodinium miocaenicum, the top of Unipontidinium aquaeductum, the occurrence of Cannosphaeropsis passio and the top of Palaeocystodinium miocaenicum.

This study has revealed some differences when comparing the positions of these events with those of Dybkjær & Piasecki (2010).

Firstly, the top of Exochosphaeridium insigne is found in both the 2/11–12S core and the 2/8G10A core above the base of Cousteaudinium aubryae and thus within the C. aubryae Zone. In Dybkjær & Piasecki (2010), this event was located below the base of C. aubryae, within the E. insigne Zone.

Next, the top of Cousteaudinium aubryae is located in both the 2/11–12S core and the 2/8–G10A core, somewhat above the FO of Labyrinthodinium truncatum, and is thus within the L. truncatum Zone. These two events were erroneously shown to occur at the same level (Dybkjær & Piasecki 2010, their figs. 6, 7), while in the description of the L. truncatum Zone, it was stated that the LO of C. aubryae occurs within that zone. The data from this study thus support the latter.

Acccording to Dybkjær & Piasecki (2010), the top of Cerebrocysta poulsenii is found at the top of the Achomosphaera andalousiense Zone. In this study, in the 2/11–12S core, two specimens of C. poulsenii were found in the same sample as the base of Gramocysta verricula, the latter defining the base of the G. verricula Zone. Unfortunately, that sample was the highest sample analysed, so it is uncertain if the top of C. poulsenii continues further up in the G. verricula Zone in the study area.

Lastly, the LO of Cleistosphaeridium placacanthum was erroneously located at two different levels in the zonation of Dybkjær & Piasecki (2010): at the top of the Achomosphaera andalousiense Zone (p. 18) and coinciding with the upper boundary of the A. umbraculum Zone (p. 19) and the lower boundary of the H. obscura Zone (p. 21). The location of the top of Cleistosphaeridium placacanthum is clearly not a good stratigraphic marker. This study indicates a gradual decrease in abundance of this species, resulting in an indistinct and poorly defined top. In the 2/11–12S core, the top of C. placacanthum was found in the upper part of the U. aquaeductum Zone. In the 2/8–G10A core, it is present in the interval referred to as the A. andalousiense Zone. In the 2/8–8 well, this species was found consistently in the upper part of U. aquaeductum Zone and sporadically at least up to and within the uppermost analysed sample at the base of the G. verricula Zone. In the 2/8–N4 well, the top occurrence of this species was found in an interval which either belongs to the upper U. aquaeductum Zone or the lower A. andalousiense Zone, and in the 2/11–1 well, the top of C. placacanthum was found in the upper part of the U. aquaeductum Zone. However, the succession above the base of the G. verricula Zone was not included in the cored sections in this study, and so, our data set does not provide a well-documented location for the LO of this species.

New events for the Danish and southern Norwegian North Sea area with potential stratigraphic use found in this study are given as follows (see Figs 5, 6, 7, 8 and Supplementary Files S1–S13):

- The LO of Ectosphaeropsis burdigalensis in either the Homotryblium spp. Zone or in the Caligodinium amiculum Zone in the 2/8-G10A well.

- The LO of Membranilarnacea cf. picena group in the upper Caligodinium amiculum Zone in the 2/11-1 well.

- The LO of Leptodinium italicum in the upper Sumatradinium hamulatum Zone in the 2/11-1 well.

- The LO of Dinopterygidium cladoides in the upper S. hamulatum Zone in the 2/8G10A core (and also in the 2/8–8 and 2/11–1 wells).

- The LO of Hystrichokolpoma cinctum in the upper Sumatradinium hamulatum Zone in the 2/11-1 well.

- The FO of Invertocysta tabulata in the lower part of the Labyrinthodinium truncatum Zone in all wells.

- The FO of Habibacysta tectata in the lower part of the Unipontidinium aquaeductum Zone in the 2/11–12S and 2/8–G10A cored wells and also in the 2/8–8 well.

- The FO of Palaeocystodinium powellense in the Unipontidinium aquaeductum Zone in the 2/11-1 well.

- The FO of Operculodinium eirikianum in the middle part of the Unipontidinium aquaeductum Zone in the 2/11–12S, 2/8–8 and 2/11–1 wells and in the middle to ?upper part of the Unipontidinium aquaeductum Zone in the 2/8–G10A well (the upper part of the zone has probably been removed by erosion or faulting, see Fig. 5).

- The FO of common Habibacysta tectata in the middle part of the Unipontidinium aquaeductum Zone in the 2/11–12S, 2/8–8 and 2/11–1 wells and in the middle to ?upper part of the Unipontidinium aqueaductum Zone in the 2/8–G10A well.

- The LO of Sumatradinium hamulatum in the upper part of the Unipontidinium aquaeductum Zone in the 2/11–12S well, and in the Achomosphaera andalousiense Zone in the 2/8–N4, 2/8–8 and 2/11–1 wells.

- The FO of common Impagidinium sp. A Wrenn & Kokinos 1996 in the uppermost part of the Unipontidinium aquaeductum Zone in the 2/11–12S and 2/8–G10A wells.

- The FO of Invertocysta lacrymosa in the basal part of the Achomosphaera andalousiense Zone in the 2/11–12S well.

- The FO of Operculodinium tegillatum in the Hystrichosphaeropsis obscura Zone in the 2/8-G10A well.

- The LO of Impagidinium sp. A Wrenn & Kokinos 1996 (common) in the Achomosphaera andalousiense Zone in the 2/8-G10A well.

Established and new dinocyst events noted in this study are illustrated in Figs 5, 6 and Supplementary Files S1–S6. The most useful dinocyst events for correlation on a local level are marked using purple correlation lines in Supplementary Files S7–S12 and combined in a correlation figure (Fig. 8 and Supplementary File S13).

9.3. Microfossils

Application of the North Sea microfossil zonations, NSB (King 1989) and NS (King 2016), referred the combined studied interval of the six wells to Aquitanian to Early Tortonian Zones NSB9 (NS34) to NSB12c (NS38–39; Figs 4–6, Supplementary Files S1–S12). The calcareous benthic foraminifera that mark the top of NSB9 (NS34; LO of Plectofrondicularia seminuda), top of NSB10 (NS35; LO of Uvigerina teniupustulata), top of NSB11 (NS36b; LO of Asterigerina guerichi staeschei) and top of NSB12 (NS39; LO of Uvigerina kingii), along with other marker planktonic microfossils from King (1989, 2016) are applied successfully in this study.

The 2/11–12S core spans Burdigalian Zone NSB10 (NS35a) to Serravallian Subzone NSB12c (NS39). The 2/8–G10A core covers Aquitanian Zone NSB9 (NS34) Langhian to Subzone NSB12a (NS36c).

While FOs and LOs of planktonic and calcareous benthic foraminifera are useful for biostratigraphic correlation in the Valhall–Hod area, abundance variations in other microfossil groups, such as agglutinating foraminfera, diatoms, radiolaria and sponge spicules, are also potentially useful for correlation. In addition, variations in the siliceous versus calcareous microfossil components are of interest regarding our understanding of the diatomite reservoir architecture and palaeoenvironment and form the basis for ongoing detailed studies.

9.4. Microfossil events

In addition to the FOs and LOs of microfossils defining zone boundaries, King (1989, 2016) also presented selected additional stratigraphically useful events. This study reveals some local observations and differences in the relative positions of some of these events (see Figs. 5, 6, 8 and Supplementary Files S1–S13) as follows:

- The FO of Globorotalia praescitula below the FO of Uvigerina tenuipustulata in the 2/11–12S and 2/8–G10A wells. In King (1983), these two events are in reverse order, although their ranges are marked as uncertain.

- The FO of Globorotalia zealandica above the FO of Uvigerina tenuipustulata in the 2/11–12S and 2/8–G10A wells. In King (1983), these two events coincide, although their ranges are noted as uncertain.

- The coinciding LOs of Globorotalia zealandica and Globorotalia praescitula just below the top of Zone NSB10 (NS35b-c) in the 2/11–12S and 2/8–G10A wells. In King (1983, 2016), the LO of Globorotalia zealandica occurs slightly earlier in NSB10 than the LO of Globorotalia praescitula.

- The LO of Trilobatus trilobus is noted within Zone NSB11 (NS36a-b) in this study. King (1983) places its LO in the lower part of Subzone NSB12a.

- The LO of Loxostomum sinuosum is seen at the top of Zone NSB11 (NS36a-b) in the 2/8–G10A, 2/11–12S, 2/8–N4 and 2/11–1 wells. The LO of Loxostomum sinuosum is found in the lower part of subzone NSB10 (Laursen & Kristoffersen 1999) onshore Denmark, at the top of NSB11 in King (1989) and at the top of NSB9 (NS34) in King (2016).

- The FO of Uvigerina kingi marks the base of NSB12c (NS38–39) in this study in the absence of Elphidium antoninum (King 1989). In King (1989), the FO of Uvigerina kingi is within subzone NSB12c with uncertainty.

We also identified new microfossil events not noted in the zonations of King (1983, 1989, 2016). These events have potential stratigraphic use and are found in the cored intervals in this study and also in some of the non-cored wells (see Figs. 5, 6, 8 and Supplementary Files S1–S13, where they are noted in red). These events are as follows:

- The LO of Globigerinelloides obliquus in the upper part of NSB10 (NS35b-c) below the LOs of Alabamina wolterstorffi and Trifarina bradyi and above the FO of Uvigerina tenuipustulata in the 2/8–G10A and 2/11–12S wells.

- The LO of Ceratobulimina contraria just below (2/8–G10A) or close to (2/11–12S, 2/8–V6, 2/11–1) the LO of Uvigerina tenuipustulata in upper NSB10 (NS35b-c). Onshore Denmark, in a shallower setting, the LO of Ceratobulimina contraria is a younger event marking the top of NSB12a (Laursen & Kristoffersen 1999).

- The LOs of Alabamina wolterstorffi and Trifarina bradyi in the upper part of NSB10 (NS35b-c) below the LOs of Globorotalia zealandica and Globorotalia praescitula in the 2/8–G10A and 2/11–12S wells. The LO of Trifirina bradyi is found in the Upper Pliocene succession in the North Sea (King 1989). Its consistent LO towards the top of NSB10 in the study area (also in the 2/8–N4, 2/8–8 and 2/11–1 wells) may be useful for local correlation.

- The LOs of Ciperoella ciperoensis and Paragloborotalia nana close to the base of NSB11 (NS36a-b) in the 2/8–G10A, 2/11–12S, 2/8–N4 and 2/8–V6 wells. The LO of Ciperoella ciperoensis was noted in the Lower Miocene succession of the Ekofisk Field (Eidvin et al. 1999).

- The LO of Globoturborotalita eolabiacrassata in the lower part of NSB11 (NS36a-b) in the 2/8–G10A and 2/11–12S wells.

- The LO of Lenticulina peregrina at or just below the top of NSB11 (NS36a-b) in the 2/8–G10A, 2/11–12S and 2/8–N4 wells.

- The LO of Cancris subconicus at the top of NSB11 (NS36a-b) in the 2/8–G10A and 2/11–12S wells.

Two additional events are identified that may have correlation potential (also marked in red in Supplementary Files S1–S12). These include the LO of Nonion cf. granosum towards the top of NSB10 (NS35b-c) in the 2/8–G10A, 2/11–12S, 2/8–N4, 2/8–8 and 2/8–V6 wells and the LOs of Ciperoella anguliofficionalis and Trilobatus quadrilobatus within subones NSB12a-b (NS36c-38) in the 2/8–G10A, 2/11–12S, 2/8–N4 and 2/8–8 wells.

Established and new microfossil events noted in this study are illustrated in Figs. 5, 6 and Supplementary Files S1–S6. The most useful microfossil events for correlation on a local level are marked using blue correlation lines in Supplementary Files S7–S12 and combined into a correlation figure (Fig. 8 and Supplementary File S13).

9.5. Calcareous Nannofossils

Approximately ten samples per well were analysed for calcareous nannofossils using basic presence–absence observations, which enabled a broad biostratigraphic breakdown into fairly long-ranging nannofossil zones, overall spanning Early to Middle Miocene zones NN3–NN6 (Martini 1971). Calcareous nannofossil ranges are based on observations of Young (1998), de Kaenel et al. (2017), Bergen et al. (2017) and Boesiger et al. (2017). Reworked nannofossils from the Upper Cretaceous and Palaeogene are present in all wells, and caved material was occasionally noted in the non-cored wells. Nannofossil events in Figs. 5, 6 and Supplementary Files S1–S12 are in black text and are not included in the correlation in Fig. 8 and Supplementary File S13 due to large sample spacing and the basic counting method applied. The relative position of Early to Middle Miocene calcareous nannofossil events from the Valhall–Hod area is shown in Fig. 7. While these events are not necessarily new, they may be useful for local and regional correlation and biostratigraphy.

The oldest nannofossil zone identified is Zone NN3 in the 2/8–8 well, recognised due to the co-occurrence of Helicosphaera bipuncta, Sphenolithus apoxis, Sphenolithus puniceus and Helicosphaera scissura. Joint zones NN3–4 are noted in the 2/8–G10A, 2/11–12S and 2/8–V6 wells based on an assemblage containing elements restricted to either zone. For example, Sphenolithus apoxis and Sphenolithus conicus (LOs in NN3), Discoaster emblematicus (FO in NN3) and Discoaster caulifloris, Discoaster petaliformis and Sphenolithus heteromorphus (FOs in NN4). Zone NN4 is identified in all wells and is characterised by the co-occurrence of Helicosphaera ampliaperta, variably with Helicosphaera waltrans, Sphenolithus puniceus, Sphenolithus heteromorphus, Helicosphaera scissura, Discoaster emblematicus, Discoaster caulifloris and Sphenolithus abies. Joint zone NN4–5 is recorded in the 2/8–G10A well, based on the co-occurrence of Helicosphaera scissura, Discoaster caulifloris, Reticulofenestra pseudoumbilicus and Discoaster discissus. The upper parts of the 2/8–N4, 2/8–8, 2/8–V6 and 2/11–1 wells are assigned a wide NN4–6 range based on the presence of Cyclicargolithus bukryi, Cyclicargolithus floridanus and Helicosphaera vedderi whose upper range is no younger than Zone NN6.

9.6. Calcareous Nannofossil events

Nannofossil events with potential correlative use and other possible useful nannofossil biostratigraphic occurrences are seen in Figs. 5, 6, 7 and Supplementary Files S1–12. They are described here in stratigraphic order in relation to NSB/NS microfossil zones (King 1989, 2016), and their relative positioning is shown in Fig. 7 against the nannofossil zonation of Martini (1971). Low resolution sample spacing and potential caving can result in depressed FOs in the non-cored wells. The events are indicated by the:

- FO of Coccolithus pelagicus in all wells at the base of the studied sections.

- FO of Cyclicargolithus floridanus in all wells at or near the base of the studied sections.

- FO of Helicosphaera carteri at the base of the studied sections in the 2/8–G10A, 2/11–12S, 2/8–N4, 2/8–8 and 2/11–1 wells.

- FO of Helicosphaera ampliaperta at the base of the studied sections in the 2/11–12S, 2/8–N4, 2/8–8 and 2/11–1 wells and slightly higher, in the upper part of NSB10 (near the base of NS35b) in the 2/8–G10A and 2/8–V6 wells.

- FO of Discoaster emblematicus at the base of the studied sections in the 2/8–G10A, 2/8–N4 and 2/8–8 wells and higher, in the upper part of NSB10 (NS35b-c) in the 2/11–12S and 2/8–V6 wells.

- FO of Reticulofenestra pseudoumbilicus in the 2/11–12S, 2/8–V6 and 2/11–1 wells towards the middle of NSB10 (NS35).

- FO of Discoaster caulifloris in the upper part of NSB10 (near the base of NS35b) in the 2/8–G10A, 2/11–12S and 2/11–1 wells and slightly higher in the 2/8–V6 well.

- FO of Discoaster exilis in the 2/8–N4, 2/8–8 and 2/11–1 wells towards the middle of NSB10 (near the base of NS35b).

- LO of Discoaster emblematicus close to the boundary of NSB10 (NS35b-c) and NSB11 (NS36a) in the 2/11–12S, 2/8–8 and 2/8–V6 wells, and slightly lower in the 2/G10A and 2/8–N4 wells.

- FO of Helicosphaera bipuncta in the 2/8–G10A, 2/11–12S and 2/8–V6 wells towards the base of NSB11 (NS36a-b) and lower, perhaps due to caving in the 2/11–1 well.

- LO of Helicosphaera ampliaperta in NSB10 (NS35) in the 2/8–G10A, 2/8–N4, 2/8–8 and 2/11–1 wells and higher, within NSB12a (NS36c) in the 2/11–12S and 2/8–V6 wells. The discrepancy in age may be due to wide nannofossil sample spacing and the thin succession represented by NSB11.

- LO of Discoaster exilis in NSB12a-b (NS36c-38) in the 2/8–N4, 2/8–8 and 2/11–1 wells.

- LO of Discoaster caulifloris within NSB11 (NS36a-b) in the 2/8–G10A and 2/11–12S wells and slightly lower, in upper NSB10 (NS35), in 2/11–1.

- LO of Helicosphaera bipuncta in NSB12 (NS36–38) in the 2/11–12S and 2/11–1 wells, and lower in NSB11 (NS36a-b) in the 2/8–G10A and 2/8–V6 wells.

- LO of Cyclicargolithus floridanus at or near the top of the studied sections in all wells.

- LO of Helicosphaera carteri at or near the top of the studied sections in all wells.

- LO of Coccolithus pelagicus in all wells at the top of the studied sections.

A more extensive study of nannofossils of the calcareous intervals was unfortunately beyond the scope of this study but would be an interesting exercise to carry out in the future.

9.7. Diatoms

Sufficiently well-preserved diatoms recorded in the cored and non-cored wells in this study allowed the application of the Early and Middle Miocene biostratigraphy of Schrader and Fenner (1976) from the Norwegian Sea. In this study, the Early Miocene Rhizosolenia norwegica–Coscinodiscus vigilans–Nitzschia maleinterpretaria joint Partial Range Zone (PRZ) to the Middle Miocene Denticulopsis hyalina PRZ are recognised (Figs. 5, 6, 8, Supplementary Files S1–S13).

Zone definitions of Schrader & Fenner (1976) and observed assemblages in this study are described here. Apart from in the 2/8–G10A core, several of the diatom species that define the tops and bases of the PRZs of Schrader & Fenner (1976) are not consistently recorded in this study. However, the diatom assemblages described in Schrader & Fenner (1976) in a particular PRZ are similar to the assemblages found here and can provide an alternative method of identifying that specific PRZ when the markers for PRZ tops and bases are not seen. New diatom events are recognised in this study within the identified PRZs in several wells. Therefore, these new events correlate across the Valhall and Hod areas and may potentially be of correlative value further afield. The chronostratigraphic age of the diatom zonations in this study (Fig. 4) is linked to the dinocyst stratigraphy of Dybkjær & Piasecki (2010) in the description that follows.

9.8. Diatom zonation

Rhizosolenia norwegica–Coscinodiscus vigilans–Nitzschia maleinterpretaria joint PRZ (Schrader & Fenner 1976)

Definition. The base of the Rhizosolenia norwegica PRZ is based on the FO of Stictodiscus aff. kittonianus and Macrora stella. The top of the Nitzschia maleinterpretaria PRZ is based on the LOs of Dimerogramma fossile, Sceptroneis ossiformis, Thalassionema harosakiensis and Thalassiosira spinosa var. aspinosa and the FO of Raphoneis margaritalimbata.

Age. Early Miocene (Burdigalian). From the lower part of the upper Sumatradinium hamulatum Zone to the lower part of the Cousteaudinium aubryae dinocyst Zone (Dybkjær & Piasecki 2010) in the 2/8–G10A cored well.

Diatom Assemblage (this study). Includes Stictodiscus aff. kittonianus, Raphoneis margaritalimbata, Opephora gemmata, Raphidodiscus marylandicus, Pseudodimerogramma elongata, Thalassiosira fraga, Rocella gelida, Rhizosolenia hebetata, Sceptroneis ossiformis, Actinocyclus ehrenbergii, Dimerogramma fossile, Actinocyclus tenellus, Stephanopyxis horridus, Diploneis smithii, Thalassionema spp. (abundant in the uppermost part), Synedra jouseana, Raphoneis amphiceros, Paralia sulcata (abundant), Chaetoceros spp. (abundant), Pseudopodosira spp. (abundant, including Pseudoporosira westii) and Actinoptychus senarius.

Observations. It was not possible to subdivide these three PRZs in this study. In the 2/8–G10A core, the base of this combined interval was based on the FO of Stictodiscus aff. kittonianus and the top by the FO of Raphoneis margaritalimbata. The FO of Stictodiscus aff. kittonianus is found with the FO of Opephora gemmata in the upper Sumatradinium hamulatum dinocyst Zone in the 2/8–G10A core. The FO of Opephora gemmata is found at a similar stratigraphic level in the 2/8–8, 2/8–V6 and 2/11–1 wells and is here used as an additional diatom event for the identification of the base of the R. norwegica–C. vigilans–N. maleinterpretaria joint PRZ. The top of this joint PRZ is marked by the FO of Raphoneis margaritalimbata in the 2/8–G10A, 2/8–8 and 2/11–1 wells (Figs. 5, 8, Supplementary Files S1, S4, S6, S7, S10, S12, S13), close to the FO of the dinocyst Cousteaudinium aubryae. The top of this PRZ in the 2/8–V6 well (Supplementary Files S5, S11) is comparatively high, but due to a lack of other marker diatoms is based on the FO of common to abundant Stephanopyxis horridus in the overlying sample, an event which is characteristic of the overlying Thalassiosira fraga PRZ. The R. norwegica–C. vigilans–N. maleinterpretaria joint PRZ is only identified in the 2/8–G10A, 2/8–8, 2/8–V6 and 2/11–1 wells.

Thalassiosira fraga PRZ (Schrader & Fenner 1976)

Definition. The base of the Thalassiosira fraga PRZ is defined on the LOs of Dimerogramma fossile, Sceptroneis ossiformis, Thalassionema harosakiensis and Thalassiosira spinosa var. aspinosa, and the FO of Raphoneis margaritalimbata. The top is based on the FOs of Coscinodiscus lewisianus, Cymatosira biharensis, Dimerogramma aff. dubium and Hemiaulus malleus and the LO of Thalassiosira fraga.

Age. Early to Middle Miocene (Burdigalian to early Langhian). From the lower part of the Cousteaudinium aubryae Zone to the lower part of the Labyrinthodinium truncatum dinocyst Zone (Dybkjær & Piasecki 2010) in the 2/8–G10A cored well.

Diatom Assemblage (this study). Includes Chaetoceros spp. (abundant), Thalassiosira fraga, Cymatosira biharensis, Raphoneis margaritalimbata, Thalassionema nitzschiodes (abundant), Paralia sulcata (abundant), Pseudopodosira spp. (common, including Pseudopodosira westii), Actinocyclus ingens (rare), Actinocyclus ehrenbergii, Raphoneis robustata, Raphoneis angulata, Raphidodiscus marylandicus, Pseudodimerogramma elongata, Stephanopyxis horridus, Diploneis smithii, Stictodiscus aff. kittonianus, Synedra jouseana, Stephanopyxis grunowii, Rhizosolenia hebetata, Rhizosolenia miocenica (rare), Raphoneis amphiceros, Pterotheca reticulata, Opephora gemmata, Cestodiscus peplum and Actinoptychus senarius.

Observations. In the 2/8–G10A, 2/8–8 and 2/11–1 wells, the base of this PRZ is based on the FO of Raphoneis margaritalimbata (Fig. 5, Supplementary Files S1, S4, S6, S7, S10, S12) close to the FO of the dinocyst Cousteaudinium aubryae. In the 2/8–G10A well, the top of this PRZ is marked by the FO of Cymatosira biharensis coinciding with the LO of Thalassiosira fraga (Fig. 5, Supplementary Files S1, S7) and in the 2/8–8 well (Supplementary Files S4, S10) by the FO of Cymatosira biharensis, in the Labyrinthodinium truncatum dinocyst Zone, below the LO of the dinocyst Cousteaudinium aubryae. In the absence of the aforementioned established markers, alternative diatom events recognised in this study in the Thalassiosira fraga PRZ are the FO of common to abundant Stephanopyxis horridus close to the base of the Labyrinthodinium truncatum dinocyst Zone in the 2/8–G10A, 2/11–12S, 2/8–8, 2/8–V6 and 2/11–1 wells. The FO of common to abundant Thalassionema nitzschiodes is also mainly noted within the Thalassiosira fraga PRZ in this study, but variably within the Cousteaudinium aubryae and Labyrinthodinium truncatum dinocyst zones, suggesting that this event is diachronous. The LO of Raphoneis margaritalimbata is noted towards the top of the Cousteaudinium aubryae dinocyst Zone in the 2/8–G10A, 2/8–8 and 2/11–1 wells, and the FO of Raphoneis robustata is noted at the same level in the 2/8–G10A and 2/11–1 wells. Both events are potentially useful. The T. fraga PRZ is identified in the 2/8–G10A, 2/11–12S, 2/8–8, 2/8–V6 and 2/11–1 wells (Figs. 5, 6, Supplementary Files S1–S2, S4–S8, S10–S12).

Rhizosolenia bulbosa PRZ (Schrader & Fenner 1976)

Definition. The base of the Rhizosolenia bulbosa PRZ is defined on the FOs of Coscinodiscus lewisianus, Cymatosira biharensis, Dimerogramma aff. dubium and Hemiaulus malleus and the LO of Thalassiosira fraga, and the top on the FOs of Denticulopsis hustedtii, Denticulopsis norwegica, Coscinodiscus endoi and Rhizosolenia miocenica.

Age. Middle Miocene (Langhian). From the upper part of the Labyrinthodinium truncatum Zone to the lower part of the Unipontidinium aquaeductum dinocyst Zone (Dybkjær & Piasecki 2010) in the 2/8–G10A cored well.

Diatom Assemblage (this study). Includes Cymatosira biharensis, Cestodiscus peplum, Raphoneis robustata, Raphoneis angulata, Pseudodimerogramma elongata, Actinocyclus tenellus, Actinocyclus ingens (rare), Diploneis smithii, Actinoptychus splendens, Synedra jouseana, Stephanopyxis horridus (abundant), Stictodiscus aff. kittonianus, Thalassionema nitzschiodes (abundant), Chaetoceros spp. (abundant), Mediaria splendida (rare), Paralia sulcata (common), Pseudopodosira spp. (common, including Pseudopodosira westii), Raphidodiscus marylandicus, Stephanopyxis turris, Stephanopyxis grunowii, Rhizosolenia miocenica (rare), Rhizosolenia hebetata, Raphoneis amphiceros, Synedra spp., Pterotheca reticulata, Opephora gemmata, Denticulopsis spp. (rare) and Actinoptychus senarius.

Observations. In the 2/8–G10A core, the base of this PRZ was based on the co-occurrence of the FO of Cymatosira biharensis and the LO of Thalassiosira fraga, and in the 2/8–8 well by the FO of Cymatosira biharensis. In the 2/8–G10A, 2/11–12S, 2/8–N4, 2/8–8 and 2/8–V6 wells, the top of this PRZ is based on the FO of Denticulopsis hustedtii. The diatoms that define the base of the Rhizosolenia bulbosa PRZ were only recorded in the 2/8–G10A and 2/8–8 wells. In the absence of these marker diatoms in the other wells, alternative diatom events are recognised in this study in the Rhizosolenia bulbosa PRZ, which are potentially useful for correlation. An influx of Synedra spp. is noted in all wells towards the base of the Rhizosolenia bulbosa PRZ, and the FO of consistent Stephanopyxis grunowii is also noted towards the base of this zone in the 2/8–G10A, 2/8–8 and 2/8–V6 wells. The LO of Stephanopyxis horridus (common to abundant) is noted in all wells towards the middle of this PRZ (Figs. 5, 6, 8, Supplementary Files S1–13). The FO of Denticulopsis hustedtii coincides in all wells with the FO of common to abundant Denticulopsis spp. (including Denticulopsis hyalina). This may be an easier event to recognise to mark the top of the Rhizosolenia bulbosa PRZ. The Rhizosolenia bulbosa PRZ is identified in all wells (Figs. 5, 6, Supplementary Files S1–S13).

Denticulopsis hyalina PRZ (Schrader & Fenner 1976)

Definition. The base of the Denticulopsis hyalina PRZ is defined on the FOs of Denticulopsis hustedtii, Denticulopsis norwegica, Coscinodiscus endoi and Rhizosolenia miocenica. The top is based on the LOs of Hemiaulus malleus, Hemiaulus malleolus and Pseudodimerogramma elongata and the FOs of the Coscinodiscus plicatus group and Rouxia californica.

Age. Middle Miocene (Late Langhian). Unipontidinium aquaeductum dinocyst Zone (Dybkjær & Piasecki 2010) in the 2/8–G10A well.

Diatom Assemblage (this study). Includes Denticulopsis hyalina, Denticulopsis hustedtii, Pseudodimerogramma elongata, Mediaria splendida (rare), Raphoneis wicomicoensis, Actinocyclus tenellus, Rhizosolenia miocenica (rare), Rhizosolenia hebetata, Cymatosira biharensis (rare), Opephora gemmata, Stephanopyxis horridus, Diploneis smithii, Actinoptychus splendens (rare), Actinoptychus heliopelta (rare), Actinocyclus ingens (common), Stephanopyxis turris, Stictodiscus aff. kittonianus, Synedra jouseana (abundant), Thalassionema nitzschiodes (abundant), Stephanopyxis grunowii, Raphoneis amphiceros, Pterotheca reticulata, Paralia sulcata (common), Chaetoceros spp. (super-abundant) and Actinoptychus senarius. Pseudopodosira spp. (common, including Pseudopodosira westii) is present throughout this PRZ and becomes abundant towards the top of the studied section.

Observations. In the 2/8–G10A, 2/11–12S, 2/8–N4, 2/8–8 and 2/8–V6 wells, the base of this PRZ was based on the FO of Denticulopsis hustedtii. This event is coincident with the FO of common Denticulopsis spp. (including Denticulopsis hyalina, Denticulopsis nicobarica (rare), Denticulopsis punctata (rare), Denticulopsis kanayae and Denticulopsis lauta) on which the base of this PRZ is based in the 2/11–1 well. A series of local LO events occur within the Denticulopsis hyalina PRZ: the LO of Thalassionema nitzschiodes (abundant), Cymatosira biharensis, Denticulopsis hyalina, Actinocyclus ingens, Diploneis smithii, Stictodiscus aff. kittonianus, Synedra spp. and common Denticulopsis spp. The top of the Denticulopsis hyalina PRZ in this study is based on the LO of high abundance and diversity diatom assemblages without evidence of species from the overlying Coscinodiscus plicatus Group PRZ and approximates to the upper part of the Unipontidinium aquaeductum dinocyst Zone. The Denticulopsis hyalina PRZ is identified in all wells (Figs. 5, 6, 8, Supplementary Files S1–S13).

9.9. Diatom events and observations from this study

Early to Middle Miocene diatom events found in the Norwegian and Iceland Seas (Schrader & Fenner 1976; Koç & Scherer 1996) used in this study are presented and discussed here and noted in black in Figs. 5, 6 and Supplementary Files S1–S12. The events are correlated with the dinocyst zonation of Dybkjær and Piasecki (2010; see Figs. 5, 6, 8 and Supplementary Files S1–S13). Selected diatom occurrences or events that were found in the Norwegian Sea and are noted sporadically in this study are found on Figs. 5, 6, and Supplementary Files S1–S12 and are also noted in black on the figures.

Boundary-defining events of Schrader and Fenner’s (1976) zonation are discussed here as follows:

- The FO of Stictodiscus aff. kittonianus defines the base of the Rhizosolenia norwegica PRZ (Schrader & Fenner 1976) and is only noted in the 2/8–G10A well at the base of the Burdigalian (upper part of the Sumatradinium hamulatum dinocyst Zone).

- The FO of Raphoneis margaritalimbata defines the base of the Thalassiosira fraga PRZ (Schrader & Fenner 1976) and is found in the 2/8–G10A, 2/8–8 and 2/11–1 wells close to the FO of the Cousteaudinium aubryae dinocyst in the middle Burdigalian Stage (Fig. 5, Supplementary Files S1, S4, S6, S7, S10 and S12). The FO of Raphoneis margaritalimbata is found in the Synedra pulchella Interval (dated as late Middle Miocene by Koç & Scherer 1996) in the Iceland Sea.

- The LO of Thalassiosira fraga marks the top of the Thalassiosira fraga PRZ and the base of the Rhizosolenia bulbosa PRZ. This Early Miocene event (Schrader & Fenner 1976) was only noted in the 2/8–G10A well in the middle of the early Langhian Labyrinthodinium truncatum dinocyst Zone.

- The FO of Cymatosira biharensis is recognised in the 2/8–G10A and 2/8–8 wells in the middle of the early Langhian Labyrinthodinium truncatum dinocyst Zone. Its FO defines the base of the Rhizosolenia bulbosa PRZ in the Norwegian Sea (Schrader & Fenner 1976), which they interpreted as a late Early Miocene event. In the Iceland Sea, its FO is noted towards the base of the Proboscia praebarboi Interval, dated as early Late Miocene by Koç & Scherer (1996).

- The FO of Actinocylus ingens (2/11–12S, 2/8–N4) or the FO of consistent Actinocylus ingens (2/8–G10A, 2/8–8, 2/8–V6, 2/11–1) is seen in all wells in the middle to upper part of the Labyrinthodinium truncatum dinocyst Zone, close to the LO of Cousteaudinium aubryae. In the Norwegian Sea, the FO of Actinocylus ingens is found in the Rhizosolenia bulbosa PRZ of Schrader & Fenner (1976), which they interpreted to be late Early Miocene in age. In the Iceland Sea, its FO is found close to the base of the Actinocylus ingens Interval (dated as late Middle Miocene by Koç & Scherer 1996).

- In the Norwegian Sea, the FO of Rhizosolenia miocenica defines the base of the Denticulopsis hyalina PRZ (and the top of the underlying Rhizosolenia bulbosa PRZ), Schrader & Fenner (1976). The FO of Rhizosolenia miocenica is seen in the 2/8–G10A, 2/8–N4, 2/8–V6 and 2/11–1 wells in the lower part of the Labyrinthodinium truncatum dinocyst Zone, in the upper part of the Thalassiosira fraga and lowermost Rhizosolenia bulbosa PRZ’s. While noting that this event defines a zonal boundary in Schrader & Fenner (1976), in this study, other events are deemed to be more useful.

Additional diatom events (FOs, LOs) noted in Schrader & Fenner (1976), and observations from this study with potential stratigraphic use in the North Sea, are presented here (see Figs. 5, 6, 8 and Supplementary Files S1–S13; marked on the figures in red) as follows:

- The FO of high abundance and diversity diatom assemblages is found in the upper part of the Sumatradinium hamulatum dinocyst Zone in the 2/8–G10A, 2/8–8, 2/8–V6 and 2/11–1 wells. In the 2/11–12S well, the event is found at the base of the Cousteaudinium aubryae dinocyst Zone, and in the 2/8–N4 well, it is found towards the base of the Labyrinthodinium truncatum dinocyst Zone, clearly displaying that this event is diachronous across the Valhall–Hod area.

- The FO of Opephora gemmata is found in the 2/8–G10A, 2/8–8, 2/8–V6 and 2/11–1 wells close to or at the FO of high abundance and diversity diatom assemblages, in the upper part of the Sumatradinium hamulatum dinocyst Zone. The FO of Opephora gemmata is found at the base of the Synedra jouseana PRZ (dated as Early Miocene by Schrader & Fenner 1976) in the Norwegian Sea.

- The FO of common to abundant Thalassionema nitzschiodes is noted in all wells, usually in the middle Cousteaudinium aubryae dinocyst Zone (wells 2/8–G10A, 2/8–8, 2/8–V6, 2/11–1) and occasionally in the lower Labyrinthodinium truncatum Zone (2/11–12S, 2/8–N4). Thalassionema nitzschiodes is consistently abundant in the Iceland Sea from the top of the Synedra pulchella Interval to the top of the Denticulopsis hustedtii Interval, dated as late Middle Miocene to early Late Miocene by Koç & Scherer (1996).

- The LO of Raphoneis margaritalimbata is recognised in the 2/8–G10A, 2/8–8 and 2/11–1 wells and wells towards the top of the Cousteaudinium aubryae dinocyst Zone. In the Iceland Sea, this event occurs in the Probiscia praeparboi Interval, dated early Late Miocene according to Koç & Scherer (1996), and in the Norwegian Sea at the base of the Cymatosira biharensis PRZ, dated Late Miocene by Schrader & Fenner (1976).

- The FO of common to abundant Stephanopyxis horridus is recognised in all wells, usually in the upper Cousteaudinium aubryae dinocyst Zone, occasionally in the lower Labyrinthodinium truncatum dinocyst Zone. In the Norwegian Sea, the base of Stephanopyxis horridus is not well defined but it is present at least from the Actinocyclus ingens PRZ, dated as Middle Miocene by Schrader & Fenner (1976).

- The FO of Raphoneis robustata is recognized in the 2/8–G10A, 2/8–N4 and 2/11–1 wells in the upper part of the Cousteaudinium aubryae or lower Labyrinthodinium truncatum dinocyst zones.

- The FO of an influx of Synedra spp. is noted in all wells at the base of the Rhizosolenia bulbosa PRZ in this study, in the lower to mid Labyrinthodinium truncatum dinocyst Zone.

- The LO of Stephanopyxis horridus (common to abundant) is recognised in all wells in the Labyrinthodinium truncatum dinocyst Zone. In the Norwegian Sea, the LO of Stephanopyxis horridus is found towards the base of the Rhizosolenia miocenica PRZ, dated as early Late Miocene by Schrader & Fenner (1976).

- The FO of consistent Stephanopyxis grunowii is recorded in all wells in the Labyrinthodinium truncatum dinocyst Zone, close to the LO of Stephanopyxis horridus (common to abundant).

- The FO of Denticulopsis hyalina is noted close to the boundary of the Labyrinthodinium truncatum and Unipontidinium aquaeductum dinocyst zones in the 2/8–G10A, 2/11–12S, 2/8–N4, 2/8–8 and 2/11–1 wells, just below or at the FO of common to abundant Denticulopsis spp. In the Norwegian Sea, the FO of Denticulopsis hyalina is close to the base of the Denticulopsis hyalina PRZ, dated as Early to Middle Miocene by Schrader & Fenner (1976).

- The FO of common to abundant Denticulopsis spp. is noted in all wells and is found towards the base of the Unipontidinium aquaeductum dinocyst Zone in the 2/11–12S, 2/8–G10A, 2/8–8 and 2/8–V6 wells and towards the top of the upper Labyrinthodinium truncatum dinocyst Zone in the 2/8–N4 and 2/11–1 wells. Denticulopsis spp. is consistently common to abundant from the Coscinodiscus norwegicus Interval, dated as Middle Miocene by Koç & Scherer (1996) in the Iceland Sea and the Denticulopsis hyalina PRZ, dated as early Middle Miocene by Schrader & Fenner (1976) in the Norwegian Sea. Common Denticulopsis spp. is noted in the upper Langhian interval in the E-8X well, Danish sector of the North Sea.

- The LO of common-abundant Thalassionema nitzschiodes is recorded in the Unipontidinium aquaeductum dinocyst Zone in most wells, not far above the FO of common to abundant Denticulopsis spp. In the Iceland Sea, this event is noted in the Proboscia barboi Interval, dated as Late Miocene by Koç & Scherer (1996).

- The LO of Diploneis smithii is recognised at or between the LO of common-abundant Thalassionema nitzschiodes and the LO of high abundance and diversity diatom assemblages in the Unipontidinium aquaeductum dinocyst Zone in the 2/8–G10A, 2/11–12S, 2/8–V6 and 2/8–8 wells and at the top of the Labyrinthodinium truncatum dinocyst Zone in the 2/11–1 well. The ‘Diploneis group’ is noted as rare occurrences in the high-latitude North Atlantic Ocean region from the Early Miocene to the Early Pliocene in Baldauf (1982).

- The LO of Actinocyclus ingens is recognised in all wells in the upper part of the Unipontidinium aquaeductum dinocyst Zone. In this study, its LO is close to the LO of Diploneis smithii. In the 2/8–N4 and 2/8–8 wells, its LO coincides with the LO of high abundance and diversity diatom assemblages. In the Norwegian Sea, the LO of Actinocyclus ingens marks the top of the Goniothecium tenue PRZ (Schrader & Fenner 1976), which is Middle Miocene in age according to Barron (1985). In the Iceland Sea, its LO marks the top of the Proboscia praebarboi Interval, dated as early Late Miocene by Koç & Scherer (1996).

- The LO of Denticulopsis hyalina is recognised in the 2/8–G10A, 2/11–12S, 2/8–8, 2/11–1 and 2/8–N4 wells just below the LO of Actinocyclus ingens and in most sections just below the LO of high abundance and diversity diatom assemblages. In the Norwegian Sea, the LO of Denticulopsis hyalina is found at the top of the Coscinodiscus plicatus PRZ, dated as Middle Miocene by Schrader & Fenner (1976).

- The LO of common Denticulopsis spp. (including Denticulopsis lauta and Denticulopsis hustedtii) is recorded in most wells in the upper part of the Unipontidinium aquaeductum dinocyst zone. In the Norwegian Sea and Iceland Sea regions, the event is found in the Denticulopsis hustedtii PRZ and Interval, dated as Late Miocene by Schrader & Fenner (1976) and Koç & Scherer (1996). In the E-8X well in the Danish sector of the North Sea, the LO of Denticulopsis spp. is noted in the Late Langhian Stage. This event coincides with the LO of high abundance and diversity diatom assemblages in the 2/8–G10A, 2/11–12S, 2/8–8 and 2/11–1 wells and is slightly below this level in the 2/8–N4 and 2/8–V6 wells.

- The LO of high abundance and diversity diatom assemblages (including Opephora gemmata, Stephanopyxis grunowii and Synedra spp.) is recognised in most wells in this study in the upper part of the Unipontidinium aquaeductum dinocyst Zone. This event coincides with the top of the Hodde Formation in the 2/8–G10A, 2/11–12S, 2/8–8 wells and the top of the Nora Formation in the 2/8–N4, 2/8–V6 and 2/11–1 wells.

Diatom events noted in this study are illustrated in Figs. 5, 6 and Supplementary Files S1–S6. The most useful diatom events for correlation on a local level are marked using green correlation lines in Supplementary Files S7–S12 and combined in the correlation figure (Fig. 8 and Supplementary File S13).

9.10. Silicoflagellates

Silicoflagellates commonly only make up about 2–3% of the biogenic part of siliceous sediments (McCartney et al. 2011). As a silicoflagellate zonation for the North Sea does not exist, the Early and Middle Miocene Norwegian Sea silicoflagellate biostratigraphy of Locker & Martini (1989) was applied, with some success, to the 2/8–G10A well and with limited success to the 2/8–N4, 2/8–8 and 2/11–1 wells (Fig. 5, and Supplementary Files S1, S3, S4, S6, S7, S9, S10, S12). The 2/11–12S and 2/8–V6 wells did not yield assemblages adequate for a silicoflagellate biostratigraphic breakdown. Two silicoflagellate zones are identified in this study: (1) the lower Corbisema triacantha Zone and (2) the upper Corbisema triacantha Zone. As this is the first time that silicoflagellate biostratigraphy has been applied to North Sea Lower-Middle Miocene deposits, zonal definitions and observed assemblages in this study are described in Section 9.10.1. The chronostratigraphy of the silicoflagellate zones is established via correlation with the dinocyst stratigraphy of Dybkjær & Piasecki (2010) and this study (Fig. 4).

9.10.1. Silicoflagellate zonation

Lower Corbisema triacantha Zone (Locker & Martini 1989)

Definition. From the LO of Naviculopsis quadratum to the FO of Mesocena diodon (now known as Bachmannocena diodon).

Age. Early to Middle Miocene (this study, Burdigalian to early Langhian, Cordosphaeridium cantharellus – Labyrinthodinium truncatum dinocyst zones, Dybkjær & Piasecki 2010).