MONOGRAPH

Lithostratigraphy of the Neogene succession of the Danish North Sea

Erik Skovbjerg Rasmussen1*  , Karen Dybkjær1

, Karen Dybkjær1  , Jørgen Christian Toft2

, Jørgen Christian Toft2  , Ole Bjørslev Nielsen3

, Ole Bjørslev Nielsen3  , Emma Sheldon1

, Emma Sheldon1  , Finn Mørk1

, Finn Mørk1

1Geological Survey of Denmark and Greenland, Øster Voldgade 10, DK-1350, Copenhagen, Denmark; 2TotalEnergies, Amerika Pl. 29, 2100, Copenhagen, Denmark; 3Department of Geoscience, Aarhus University, Høegh-Guldbergs Gade 2, 8000 Aarhus, Denmark

Citation: Rasmussen et al. 2025: GEUS Bulletin 61. 8368. https://doi.org/10.34194/0nydbt40

Copyright: GEUS Bulletin (eISSN: 2597-2161) is an open access, peer-reviewed journal published by the Geological Survey of Denmark and Greenland (GEUS). This article is distributed under a CC-BY 4.0 licence, permitting free redistribution, and reproduction for any purpose, even commercial, provided proper citation of the original work. Author(s) retain copyright.

Received: 26 Jan 2024; Re-submitted: 15 Jul 2025; Accepted: 3 Sep 2025; Published: 26 Dec 2025

Competing interests and funding: The authors declare no competing interests.

Maersk Oil, now TotalEnergies, funded biostratigraphic analysis of a number of North Sea wells and provided seismic data for the study. In addition, GEUS and Maersk Oil funded the sedimentology, the seismic study and the sequence stratigraphic interpretations.

*Correspondence: esr@geus.dk

Keywords: Neogene, Miocene, Pliocene, North Sea, lithostratigraphy, palaeogeography

Abbreviations

BCU: Base Cretaceous Unconformity

bKB: below Kelly Bushing

DGU: Dansk Geologisk Undersøgelse (Geological Survey of Denmark)

MCO: Miocene Climatic Optimum

MD: measured depth

MMCT: Middle Miocene Climate Transition

MMU: mid-Miocene Unconformity

MRS: maximum regressive surfaces

NSB: North Sea Benthic

PETM: Paleocene–Eocene Thermal Maximum

RMS: root mean square

TL: Top Lark

Edited by: Jon Ineson (Geological Survey of Denmark and Greenland)

Reviewed by: Ole Rønø Clausen (Aarhus University, Denmark) and Dirk K. Munsterman (Geological Survey of the Netherlands)

Abstract

The Neogene of the Danish North Sea is more than 1200 m thick. Despite being penetrated by numerous wells, formal lithostratigraphic subdivision of this succession has previously been restricted to the lowermost part. This monograph presents a comprehensive lithostratigraphy of the offshore Neogene of Denmark, in part extending recognised onshore units into the offshore realm. The mainly Lower Miocene deltaic deposits are referred to the Ribe Group, which is subdivided into six formations: the Klintinghoved, Bastrup, Arnum, Odderup, Dany (new) and Nora (new) Formations. The lowermost Miocene Vejle Fjord and Billund Formations known from the onshore lithostratigraphy are absent in the offshore wells. The dominantly fully marine Middle and Upper Miocene sediments are referred to the Måde Group, subdivided into the Hodde, Ørnhøj, Gram, Marbæk and Luna (new) Formations; the Luna Formation includes the Lille John Member (new). The Pliocene deltaic deposits are referred to the Eridanos Group (new), which is subdivided into the Vagn (new), Emma (new) and Elin (new) Formations.

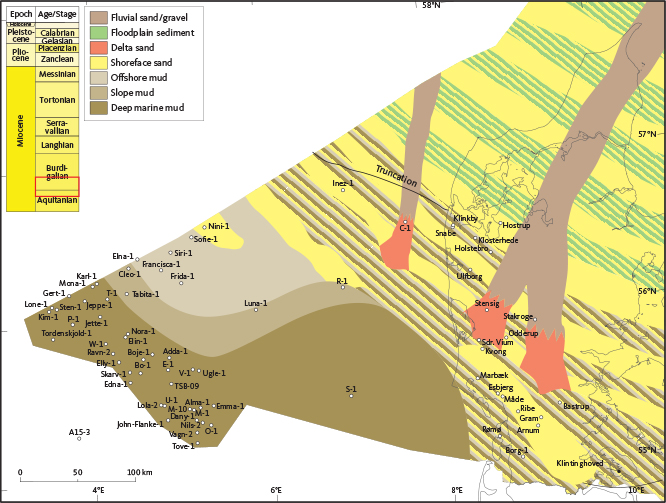

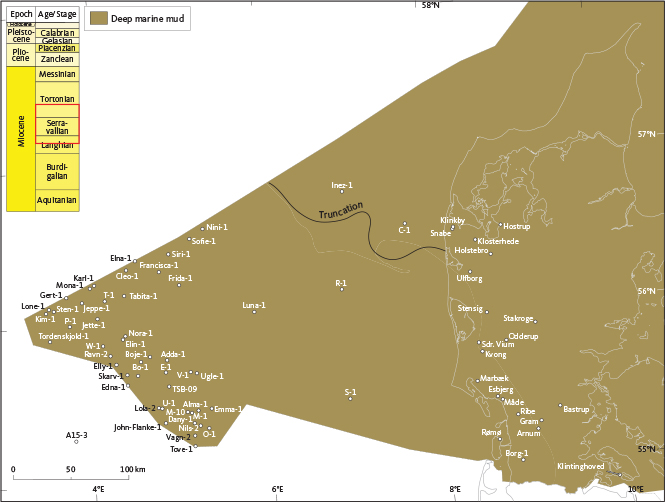

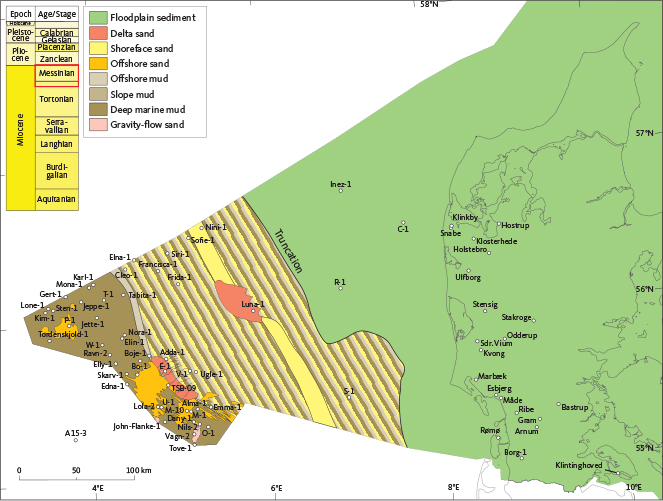

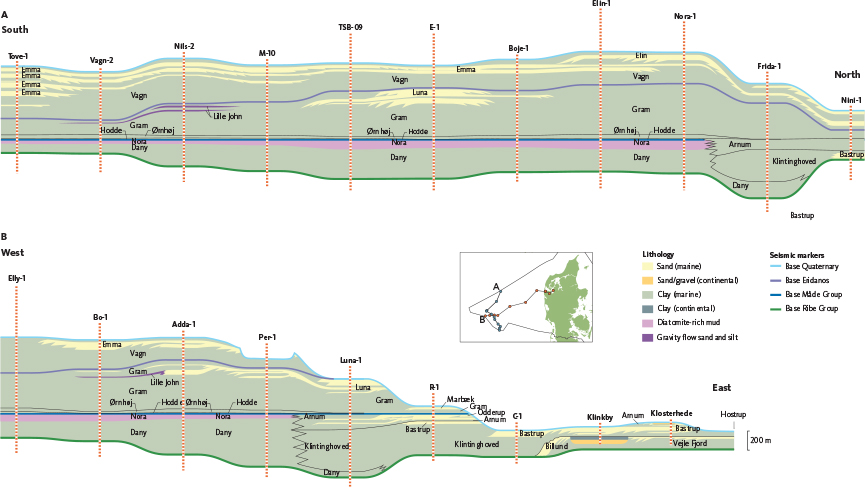

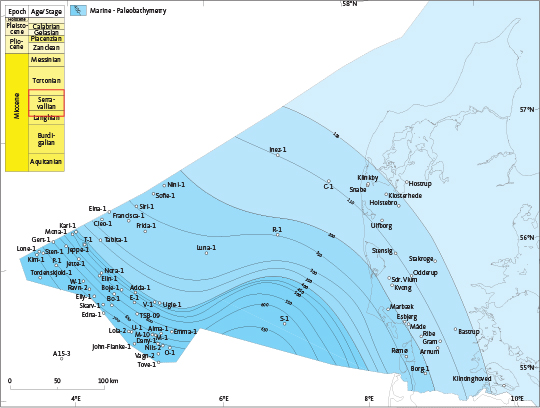

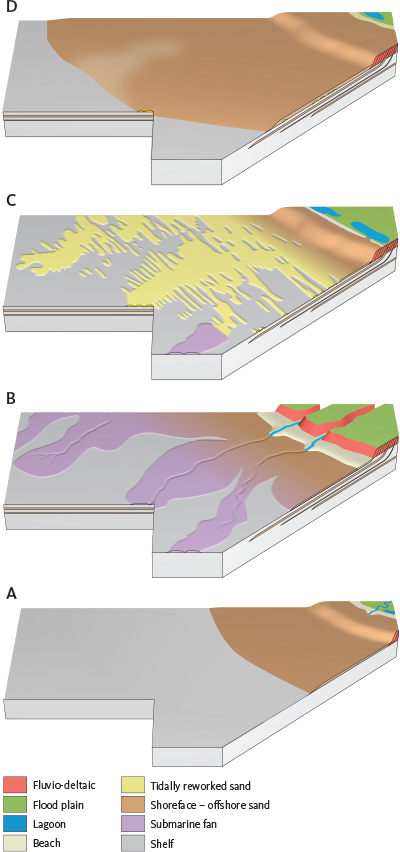

The depositional history of the Neogene of the Danish North Sea sector is presented based on a detailed reconstruction of subsurface morphology by the mapping of stratigraphical surfaces dated by biostratigraphy. During the Early Miocene, deposition in the Danish North Sea was dominated by progradation from Scandinavia; large deltas built out into the Danish onshore area from the north and north-east. West of the main deltas, muddy contourites periodically accumulated on the slope, accentuating shelf progradation. The Middle and Late Miocene period was mostly characterised by fully marine conditions and deposition of mud. By the end of the Miocene, progradation of delta systems from Scandinavia into the North Sea resumed, and the shoreline reached the westernmost part of the Danish North Sea sector. During the Pliocene, new source areas in central and eastern Europe, such as the Carpathian Mountains, were activated and a huge delta system, the so-called Eridanos Delta, began to fill the North Sea Basin from the east and the south-east. Due to increased subsidence of the basin associated with the loading of sediments of the Eridanos Delta, the northern systems were flooded. Although the Danish North Sea thus mainly received sediments from central Europe during the Pliocene, progradation from Scandinavia resumed at the end of the Pliocene.

1 Introduction

In 2010, the lithostratigraphy of the onshore Upper Oligocene – Miocene sedimentary succession in Denmark was comprehensively revised (Rasmussen et al. 2010). Although founded on previous definitions of lithostratigraphic units (Sorgenfrei 1940, 1957; Larsen & Dinesen 1959; Rasmussen 1961; Koch 1989; Christensen & Ulleberg 1973; Heilmann-Clausen 1997), the acquisition of a large amount of new information including high-resolution seismic data, boreholes that penetrated the entire Neogene succession, and particularly the development of a robust biostratigraphy (Dybkjær & Piasecki 2010), demanded a redefinition of the existing lithostratigraphy.

Since then, interest in the Neogene succession offshore has increased due to the abandonment of certain oil fields, additional hydrocarbon exploration, potential storage of CO2 in Neogene aquifers and the need to test the rock properties associated with the construction of offshore windmill parks. To support such future studies, the lithostratigraphic framework of Rasmussen et al. (2010) is expanded here to include the offshore Neogene succession in the North Sea (Fig. 1).

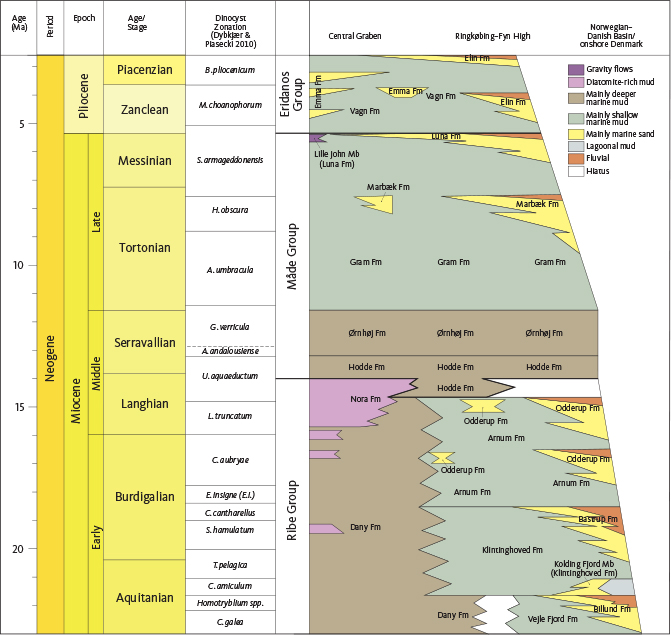

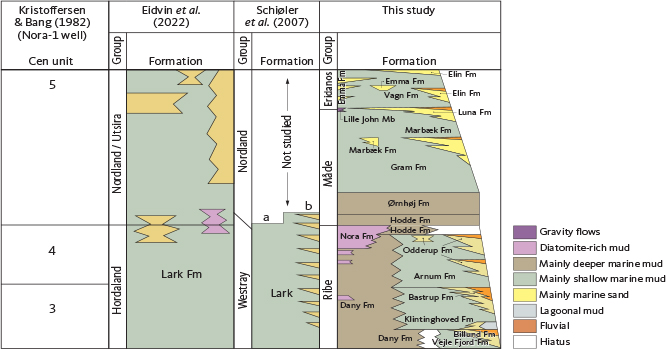

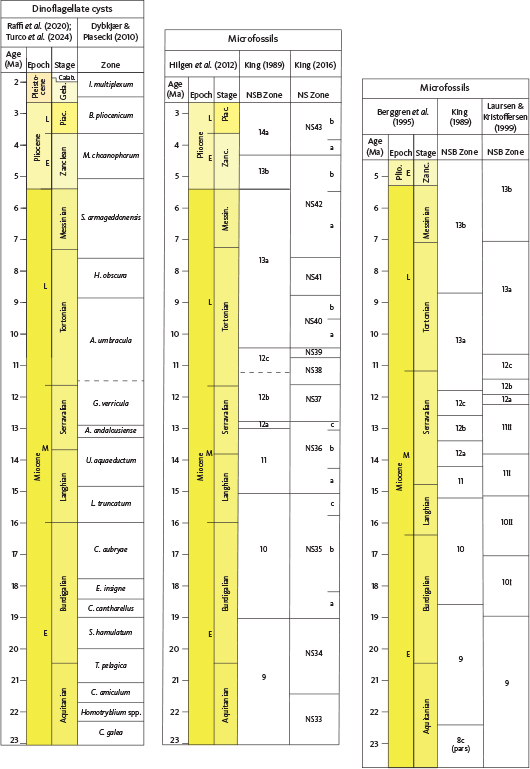

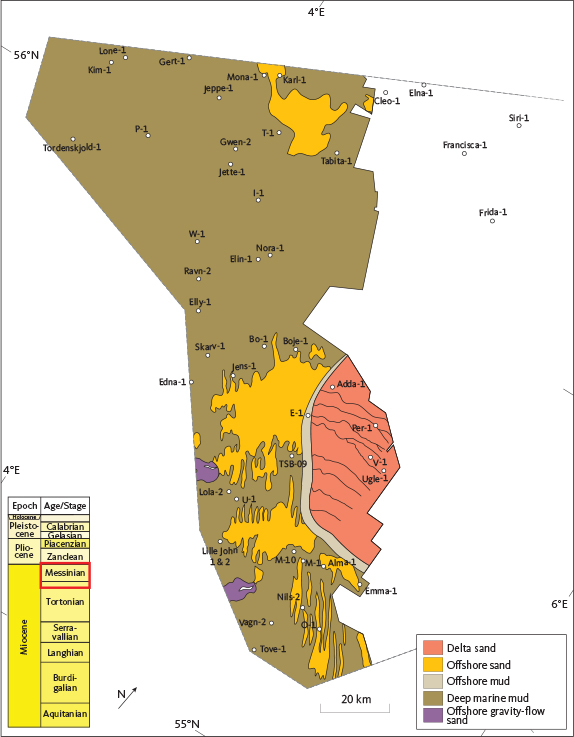

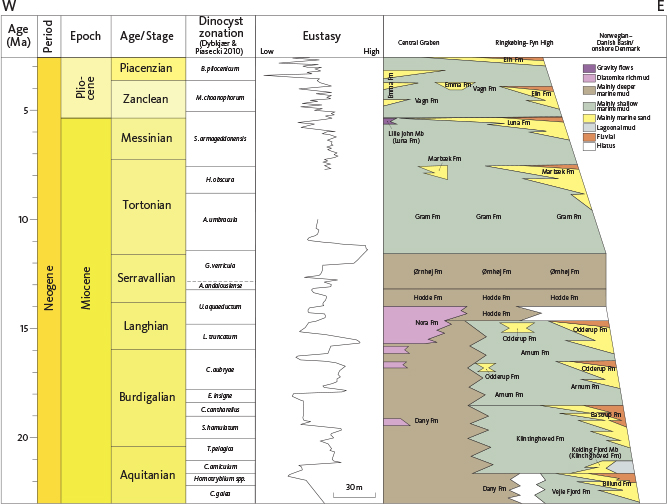

Fig. 1 The lithostratigraphy of the Neogene succession of on- and offshore Denmark, the former modified from Rasmussen et al. (2010).

The Neogene lithostratigraphic subdivision presented here (Fig. 1) is based on a multidisciplinary study incorporating seismic stratigraphy, log data and biostratigraphy. The study area, seismic data and wells and boreholes included in the text or figures are shown in Fig. 2. The age relationships of the lithostratigraphic units defined herein are based on previously published biostratigraphic studies, including Michelsen et al. (1998), Laursen & Kristoffersen (1999), Schiøler (2005), Schiøler et al. (2007), Dybkjær & Rasmussen (2007), Dybkjær & Piasecki (2010), Dybkjær et al. (2012, 2021) and Sheldon et al. (2025). These references, together with a number of unpublished biostratigraphic data sets and reports, have been used in order to refer the lithostratigraphic units to biozones and to describe their fossil content.

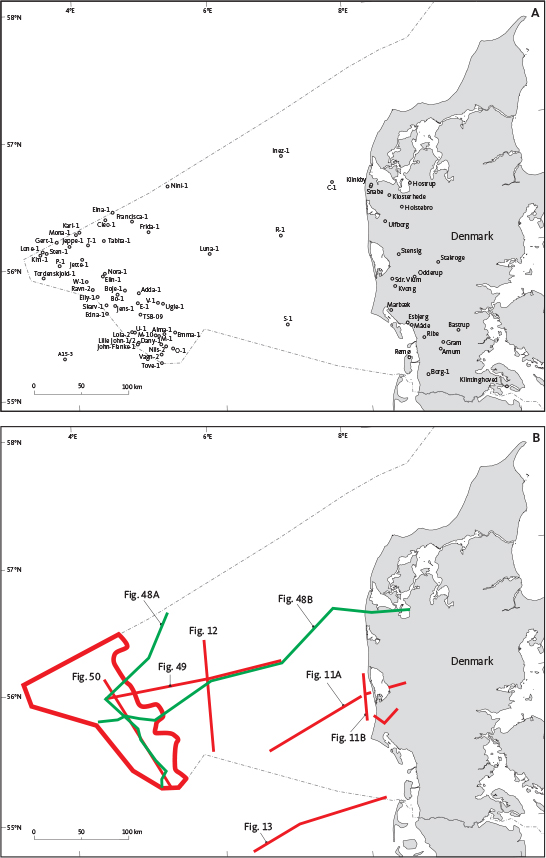

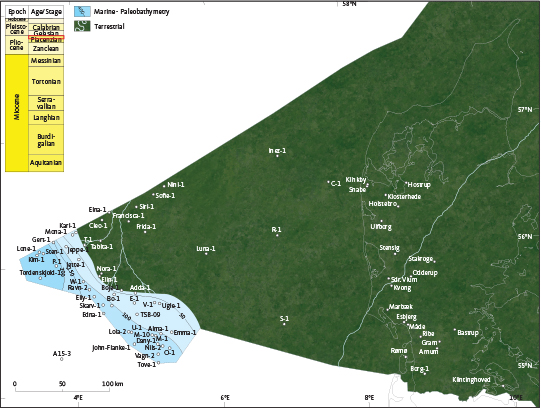

Fig. 2 Map showing the study area, wells, seismic sections coverage and local names. (A): Location of boreholes, wells, outcrops, villages and other locations mentioned in the text. (B): Location of seismic key sections and the 3D seismic survey covering the Central Graben area are shown in red and well correlation panels in green.

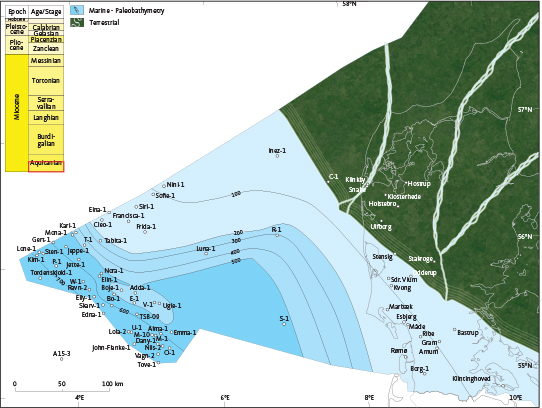

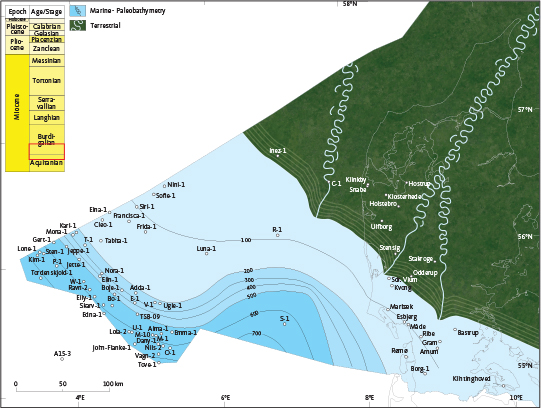

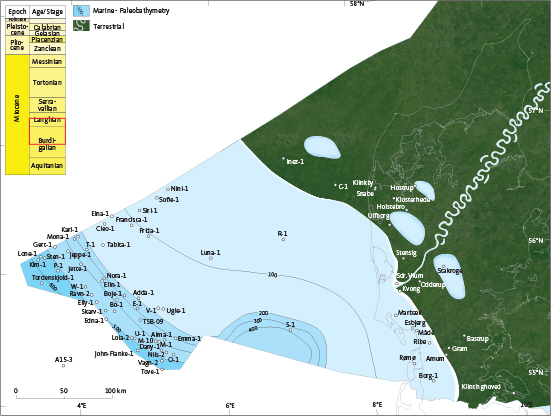

Detailed analyses of the climate have been undertaken for the Miocene succession in Denmark (Larsson et al. 2011 and references therein; Herbert et al. 2020; Śliwińska et al. 2024) and the Pliocene climate is well known from Germany (Utescher et al. 2009). These studies of the palaeoclimate combined with the distribution of the deposits onshore documented by Rasmussen et al. (2010) allow us to reconstruct the detailed palaeogeography, including the palaeobathymetry, of the Neogene in the Danish sector of the North Sea.

The aim of this study is to establish a lithostratigraphy for the Neogene succession in the offshore Danish North Sea sector and to reconstruct the palaeogeography in the study area. This new lithostratigraphy should form a robust framework for future studies such as mapping of aquifers for wastewater, CO2 storage or to ensure proper base maps for the foundation of windmill constructions in the North Sea area.

2 Geological setting

2.1 Tectonic framework

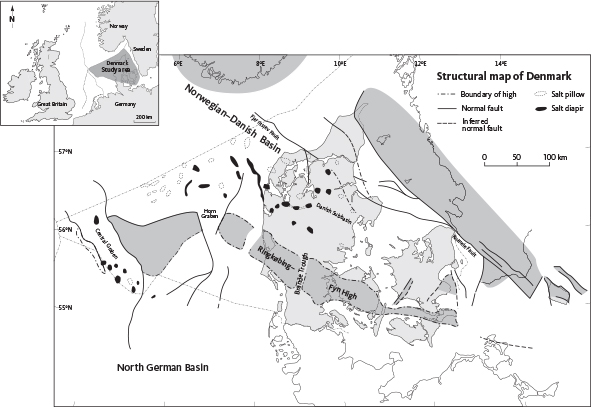

The basement of the North Sea was mainly formed during the Caledonian Orogeny in the Late Ordovician – Early Devonian (Coward et al. 2003; Pharaoh et al. 2010; Phillips et al. 2016 and references therein). The compressional tectonic regime was followed by orogen-scale extension by reactivation of pre-existing structures (Caledonian collapse; Gee & Stephens 2020 and references therein). The final phase of the formation of Pangea (the Variscan Orogeny), during the Late Devonian – Carboniferous, was succeeded by an extensional phase during the Carboniferous – Early Permian, which led to the formation of major horst and graben structures in the North Sea area, for example the Norwegian–Danish Basin, the Ringkøbing–Fyn High and the North German Basin (Fig. 3). Subsequent post-rift thermal subsidence resulted in the development of the North and South Permian Basins (Ziegler 1982, 1990).

Fig. 3 Structural elements of the Danish area. Most of the elements were formed during the Carboniferous and Permian but also active during the Mesozoic. Reactivation of some of the structures, for example inversion, occurred during the Cenozoic. From Bertelsen (1978).

The Mesozoic was characterised by extension during the Late Permian – Early Triassic, resulting in the formation of the Horn Graben, the Brande Trough and initial rifting in the Central Graben area along N–S-trending faults (Møller & Rasmussen 2003; Nøttvedt et al. 2008). Renewed rifting occurred during the Late Jurassic – Early Cretaceous, but this time along NNW–SSE-striking fault systems; this was the main phase of the formation of the Central Graben (Møller & Rasmussen 2003). The last throes of this rift phase during the earliest Early Cretaceous resulted in rotation of fault blocks, local inversion (Rasmussen 1994) and the development of a major regional unconformity (the Base Cretaceous Unconformity, BCU). During the remainder of the Cretaceous, basin development was dominated by thermal subsidence centred on the Central Graben area; regional subsidence was interrupted by post mid-Cretaceous inversion tectonism (Vejbæk & Andersen 2002; Vejbæk et al. 2006).

Ongoing post-rift thermal subsidence since mid-Cretaceous times, progressive opening of the northern Atlantic Ocean, and African-European collision drove the Cenozoic development of the North Sea Basin. Inversion of former graben structures and reactivation of salt structures occurred periodically but was most pronounced in the Selandian (Ziegler 1982; Liboriussen et al. 1987; Mogensen & Jensen 1994; van Wees & Cloething 1996 Clausen et al. 1999; Rasmussen et al. 2008) and in the Early Miocene (Rasmussen 2004a, 2009a, 2013; Green et al. 2018). These inversion phases were caused by compression associated with the Alpine orogeny (Ziegler 1982; Rasmussen 2009a, 2013). The Oligocene and Miocene were also periods of increased volcanism in NW Europe (Mayer et al. 2013). During the Middle Miocene, accelerated subsidence of the basin commenced. The cause of this change in subsidence rate is not clear, but it coincides with the formation of major inversion structures in the North Atlantic (Løseth & Henriksen 2005; Doré et al. 2008; Stoker et al. 2010) and thus probably resulted from a change in tectonic stress regime in NW Europe. This may have led to relaxation of former basin segments that were under compression during the Alpine phase, for example the Norwegian–Danish Basin. Neogene uplift associated with the Iceland plume and its branches, for example under southern Norway, has also received interest in recent years (Rickers et al. 2013; François et al. 2018). The tectonic evolution of the Miocene succession in Denmark shows a remarkable correlation with V-shaped ridges around Iceland that are attributed to changes in mantle convection (Jones et al. 2002; Rasmussen 2009a).

During the Quaternary, marked tilting of the basin occurred, resulting in very high sediment accumulation in the centre of the North Sea Basin and erosion on the flanks (Japsen 1993; Rasmussen et al. 2005; Ottesen et al. 2018). The cause of this tilting is strongly debated (Japsen et al. 2002; Nielsen et al. 2009; Gabrielsen et al. 2010; Chalmers et al. 2010), and no clear mechanisms or combination of processes have so far been found.

2.2 Cenozoic climate

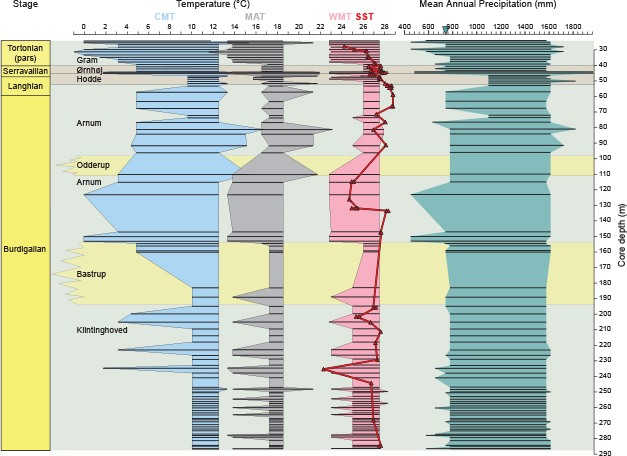

The Paleogene and Neogene climate in NW Europe was generally warm temperate and humid (Utescher et al. 2000; King 2006; Larsson et al. 2011; Śliwińska et al. 2024). An extreme, transient warm period, the so-called Paleocene–Eocene Thermal Maximum (PETM) occurred at the Paleocene–Eocene boundary (e.g. Crouch 2001; Zachos et al. 2005; Sluijs et al. 2006; Westerhold et al. 2009; McInerney & Wing 2011; DeConto et al. 2012; Jones et al. 2019; Kender et al. 2021; Mariani et al. 2024). After a warm Eocene period, cooling at the Eocene–Oligocene boundary marked the change from Mesozoic – early Cenozoic greenhouse climate to the late Cenozoic icehouse climate that persists to the present (Miller et al. 1991; Zachos et al. 1996, 2001). Despite the overall late Cenozoic icehouse climate, the Late Oligocene and Early Miocene periods were relatively warm and humid. Local studies reveal that the Late Oligocene and Early Miocene were characterised by a warm temperate climate with a mean annual temperature of c. 19˚C, and with precipitation in the order of 1300–1500 mm per year (Fig. 4; Śliwińska et al. 2024). By the end of the Early Miocene, the warm climate peaked in the so-called Miocene Climatic Optimum (MCO) (Utescher et al. 2000, 2011; Zachos et al. 2001; Larsson et al. 2011; Śliwińska et al. 2024). At the end of the Middle Miocene, a distinct climatic deterioration, the Middle Miocene Climate Transition (MMCT) commenced, which resulted in one of the most marked global sea-level falls in pre-Quaternary time (John et al. 2011); the sea-level fall was in the order of 70 m. During the Late Miocene, the equable climate, characteristic of a greenhouse period, ultimately shifted to the modern world climate with strong equator to pole temperature gradients (Herbert et al. 2016). Sea-surface temperatures of the eastern North Sea were relatively high during the late Aquitanian to early Tortonian, varying between 23 and 28˚C, and peaking during the MCO (Fig. 4; Herbert et al. 2020). A strong cooling phase in both the terrestrial and marine signals from the southern North Sea Basin was recorded during the late Tortonian (Donders et al. 2009). Minor ice caps probably formed in Greenland around 7 Ma (Larsen et al. 1994; Fronval & Jansen 1996), and during the Messinian a significant sea-level fall was associated with the build-up of ice caps in both the southern and the northern hemispheres (DeConto et al. 2008; Ohneiser et al. 2015). The Early Pliocene saw a transient warming of c. 2˚C in northwest Europe (Crampton-Flood et al. 2018, 2020), but otherwise the Pliocene climate was comparable to the modern world climate.

Fig. 4 Reconstruction of the climate during the Miocene based on the Sdr. Vium core (modified from Sliwinska et al. 2024). To the left: land temperature (CMT: coldest month temperature. MAT: mean annual temperature. WMT: warmest month temperature) and to the right: sea surface temperature (SST) and precipitation. The green arrow on the precipitation scale indicates the mean annual precipitation in Denmark, 1981–2020.

2.3 Cenozoic sedimentation

Sediment influx to the North Sea Basin during the Cenozoic was strongly influenced by uplift of terranes around the North Sea Basin. During the Paleocene and Eocene, uplift of the Atlantic margin associated with volcanic activity and opening of the North Atlantic, resulted in high sediment supply to the northern part of the basin from the Shetland Platform, the Grampian High (UK) and Scandinavia, for example via Sognefjorden and Storfjorden in Norway (Knox et al. 2010; Sømme et al. 2013). Most of the basin was dominated by pelagic and hemipelagic deposition and a significant proportion of the succession in the Central North Sea Basin consists of clay transformed from volcanic ash (Nielsen et al. 2015; Rasmussen 2019), sourced from the North Atlantic and Greenland (Larsen et al. 2003). In the southern part of the basin, delta progradation is represented by the Geiseltal, Profen and Borna Formations in the Netherlands (Knox et al. 2010).

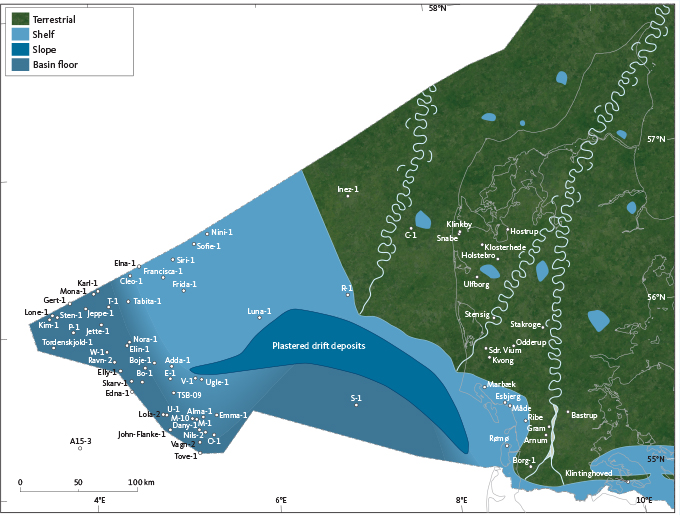

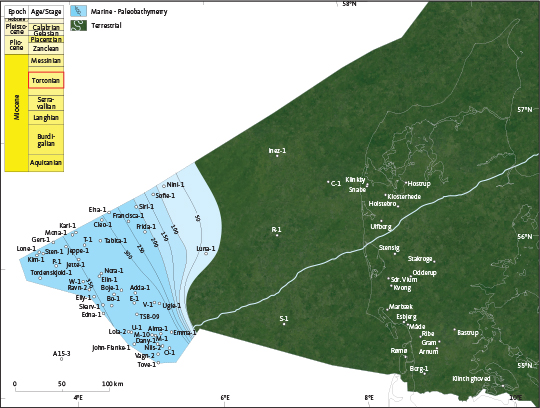

During the Oligocene and Early Miocene, uplift of Scandinavia (Rohrmann & van der Beek 1996; Rasmussen 2004a; 2013; 2019; Rundberg & Eidvin 2005; Japsen et al. 2007; Rickers et al. 2013; Sømme et al. 2013; François et al. 2018) resulted in a new and marked sediment influx into the eastern North Sea Basin (Fig. 5A; Schiøler et al. 2007; Rasmussen et al. 2010). The new source area in Scandinavia covered present-day southern Norway, including Jotunheim and central Sweden (Olivarius 2014). Coarse-grained clastic sediments were shed into the eastern North Sea Basin and formed delta systems across present-day Denmark. West of the deltas, plastered contourites draped the slope of the prograding shelf (Fig. 6), while the central part of the North Sea area was still dominated by hemipelagic deposition. In the northern part of the North Sea, delta progradation continued off the Shetland Platform during the Neogene. Density-flow deposits were laid down in the basinal areas. The southern North Sea was characterised by a paralic depositional environment with significant brown-coal formation (Schäfer et al. 2005; Standke 2006; Munsterman et al. 2019; Deckers & Louwye 2020; Deckers & Munsterman 2020).

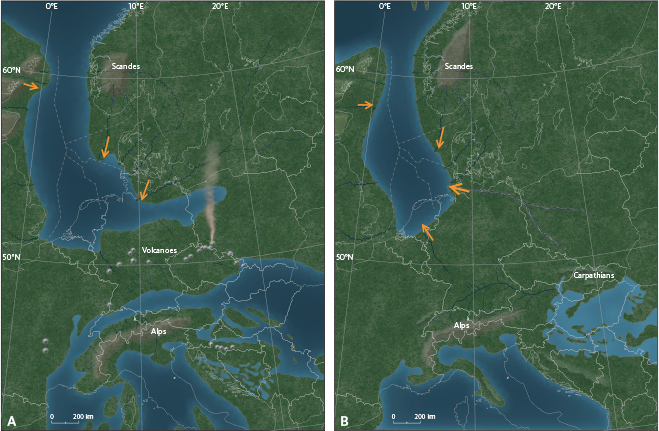

Fig. 5 Palaeogeography of NW Europe during the Early (A) and Late Miocene (B); the arrows illustrate the dominant sediment transport directions. Note that during the Early Miocene, the Shetland Platform was the main source of sediments in the northern part of the North Sea whereas Scandinavia sourced the eastern portion of the North Sea; the Alps were disconnected from Central Europe at this time due to both an arm of the northern Tethys and uplift linked to volcanism. This pattern changed during the Late Miocene. Based on Kuhlemann (2007) and Rasmussen et al. (2008).

Fig. 6 Palaeogeographic reconstruction of the Lower Miocene delta systems in the eastern North Sea. Note that the main delta system was located across Jylland and the eastern portion of the North Sea, and that the associated contourite system predominates west of the main delta system.

Most of the Middle Miocene was characterised by sediment starvation due to increased subsidence of the basin (Rasmussen 2004a; Rasmussen & Dybkjær 2014; Munstermann et al. 2019), resulting in the development of a condensed section. Within the central and deeper portions of the basin, hemipelagic sedimentation occurred (Rasmussen et al. 2005). Diatom ooze was deposited locally (Koch 1989; Rasmussen 2004a; Sheldon et al. 2018, 2025).

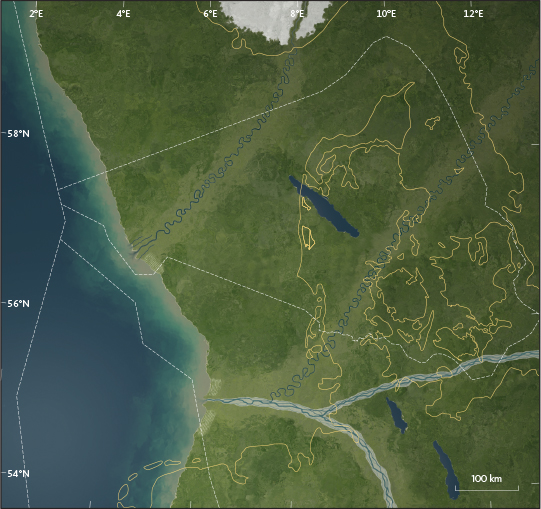

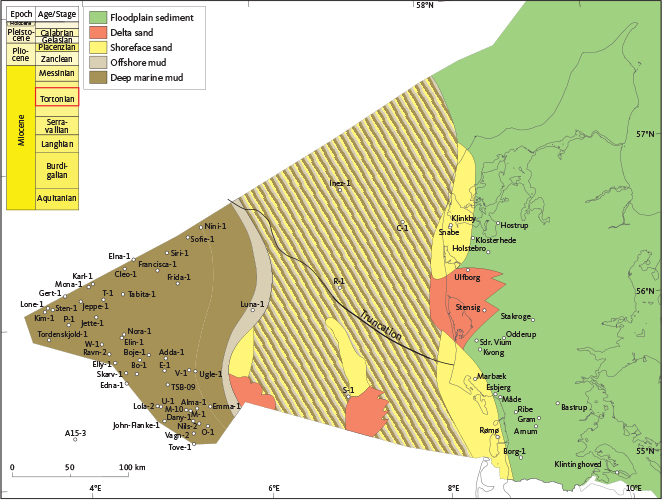

The rise of the Carpathian and Jura mountains and filling of the Alpine Foreland Basin during the Middle and Late Miocene (Oszczypko 2006; Kuhlemann 2007; Kalifi et al. 2020) created a new significant source area in central Europe (Fig. 5B). After the Middle/Late Miocene transition, the Rhenish Massif uplift instigated progradation in Germany and in the south-eastern Netherlands of the proto-Rhine fluvio-deltaic Inden Formation (Schäfer et al. 2005; Utescher et al. 2021) and the overlying latest Tortonian Kieseloölite Formation (Munsterman et al. 2019; Deckers & Louwye 2020). Huge fluvio-deltaic systems developed, such as the palaeo-Elb in eastern Germany (Eissmann 2002) and later the palaeo-Rhine-Meuse system (Schäfer 2005; Munsterman et al. 2019; Deckers & Louwye 2020), and a significant portion of the southern North Sea Basin was filled with siliciclastic deposits. The palaeo-Elb delta system, commonly referred to as the Baltic River system or the Eridanos Delta system (Bijlsma 1981; Overeem et al. 2001; Knox et al. 2010; Gibbard & Lewin 2016), dominated the southern and central realm of the North Sea during the Late Miocene, Pliocene and early Pleistocene (Fig. 7; Kuhlmann et al. 2006a, b; Noorbergen et al. 2015; Donders et al. 2018).

Fig. 7 Palaeogeographic reconstruction of the Pliocene Eridanos delta. The development of delta systems in Central Europe was strongly associated with the Alpine Orogen. Note snow in Scandinavia. The indicated locations of rivers and lakes are arbitrary.

3 Previous work

The offshore Neogene succession of the Danish North Sea sector has not previously been formally subdivided into lithostratigraphic units in the detail presented here. Kristoffersen & Bang (1982) subdivided the entire post-chalk succession into seven informal units: Cen-1 to Cen-7. Parts of Cen-3 and the Cen-4 and Cen-5 units together correspond to the Neogene section studied here (Fig. 8). Schiøler et al. (2007) referred the Lower and lower Middle Miocene to the upper Lark Formation, which was originally defined in the British and Norwegian sectors of the North Sea by Knox & Holloway (1992).

Fig. 8 Figure showing the relationship of the new lithostratigraphy presented here with the previous stratigraphic schemes of Kristoffersen & Bang (1982), Schiøler et al. (2007) and Eidvin et al. (2022). Note an inconsistency in the scheme of Schiøler et al. (2007) concerning the definition of the top of the Lark Formation: (a): Boundary inferred from the log pick in their fig. 51 at a marked shift towards higher gamma-ray readings; this log motif corresponds to the base of the Hodde Formation (see Rasmussen et al. 2010). (b): Boundary placed at the top of the Hodde Formation in their stratigraphic scheme (their fig. 2).

The comprehensive work of King (2016) presents a review of the literature on the Palaeogene and Neogene stratigraphy and a revised unified biostratigraphic/lithostratigraphic framework for the three areas: (1) The North Sea Basin (excluding southern England), (2) onshore areas of southern England and the eastern English Channel area and (3) the North Atlantic margins.

Different approaches of applying sequence stratigraphy to the offshore Danish Neogene succession have been presented by a group at the University of Aarhus (e.g. Michelsen 1994; Michelsen et al. 1995, 1998; Sørensen et al. 1997; Huuse & Clausen 2001; Gołędowski et al. 2012). The most detailed of these is the study of Michelsen et al. (1998), which is based on a sequence stratigraphic study including well logs and biostratigraphy. Michelsen et al. (1998) subdivided the Cenozoic succession into seven units. The section studied here corresponds to most of their unit 5 and all of their units 6 and 7. Rasmussen et al. (2005) subdivided the Middle–Late Miocene and Pliocene into five sequences.

Eidvin et al. (2014a) correlated the sequence stratigraphic framework of the Danish Neogene succession, including the onshore studies of Rasmussen (1996, 2004b, 2009b) and Rasmussen & Dybkjær (2005) and the offshore subdivision of Rasmussen et al. (2005), with the Norwegian sector (Fig. 8). This correlation was based on the biostratigraphic studies of Dybkjær & Piasecki (2010) and Eidvin et al. (2014a) and provided a much higher stratigraphic resolution than previously reported. In addition to the new biostratigraphy, Sr-isotope data were introduced by Eidvin et al. (2014b, 2020) which led to a very high confidence of both age assignments and regional correlation of the Neogene succession in the eastern and northern North Sea, especially for the Lower Miocene succession.

Dybkjær et al. (2021) recently presented a stratigraphic framework for the Neogene succession offshore Scandinavia based on a combination of dinocyst stratigraphy and seismic data. Documentation of the dinocyst biostratigraphy, both onshore and offshore Denmark, combined with seismic mapping in the offshore sector has facilitated correlation with the Neogene of Germany, Belgium and the Netherlands (e.g. Köthe 2007; Knox et al. 2010; Utescher et al. 2012; Thöle et al. 2014; Munsterman et al. 2019; Deckers & Louwye 2020).

4 Data and methodology

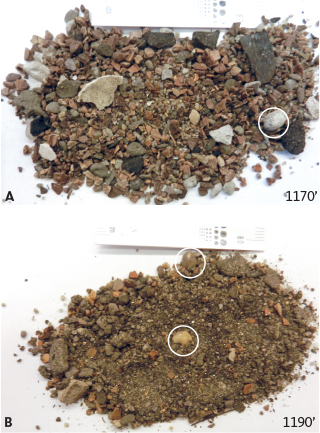

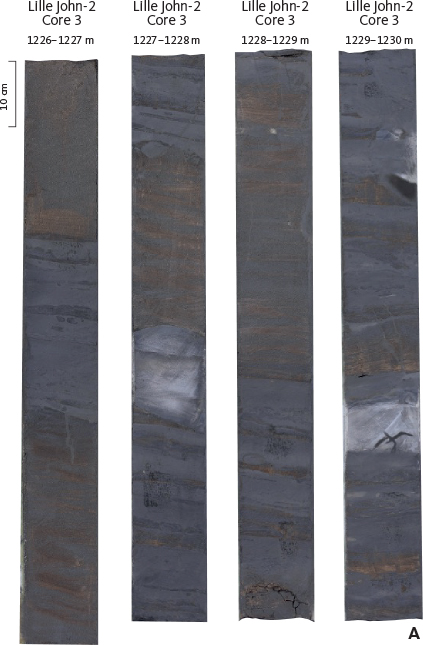

4.1 Core and cuttings description

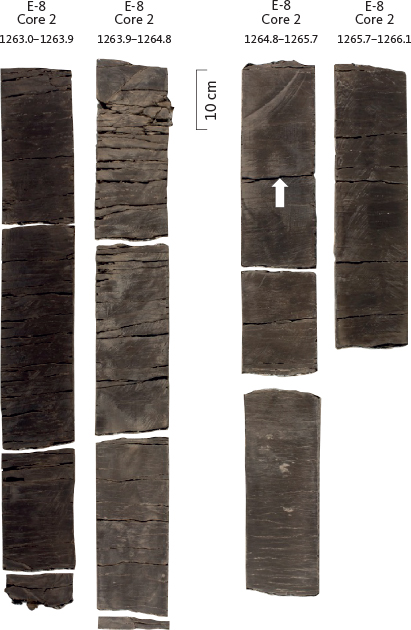

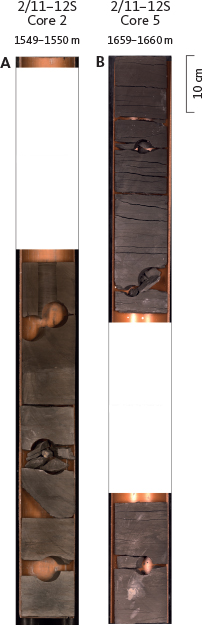

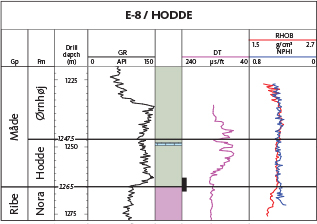

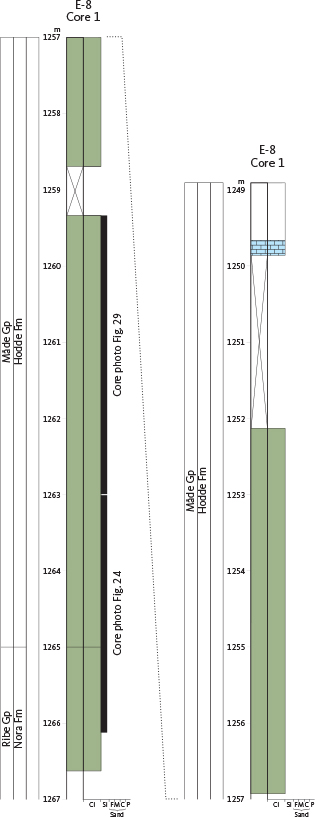

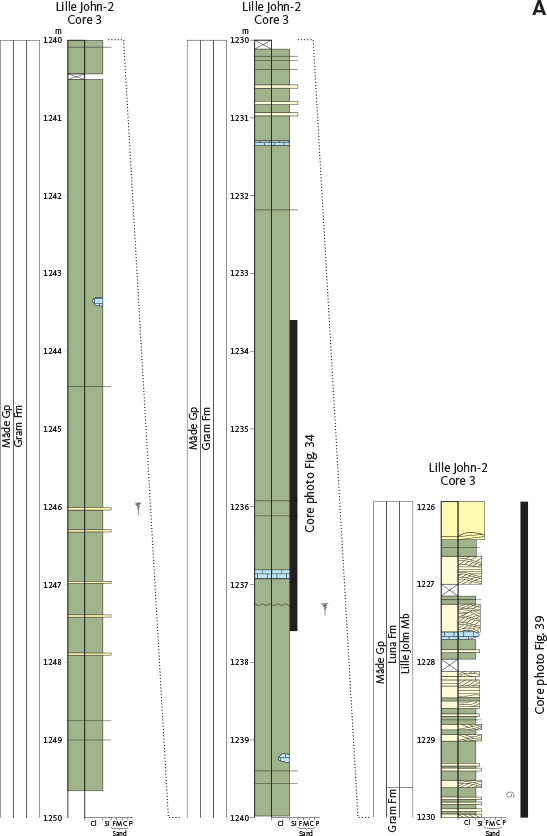

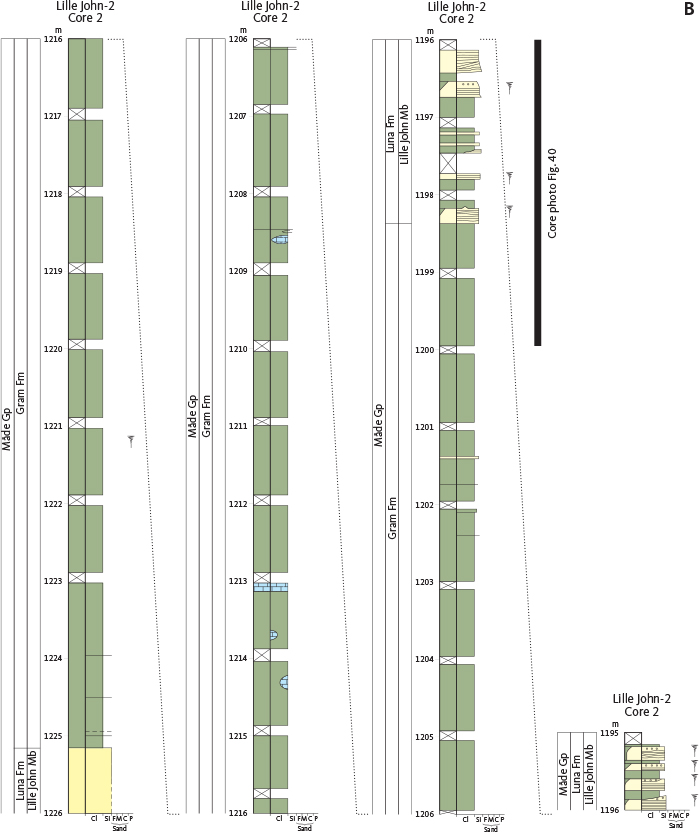

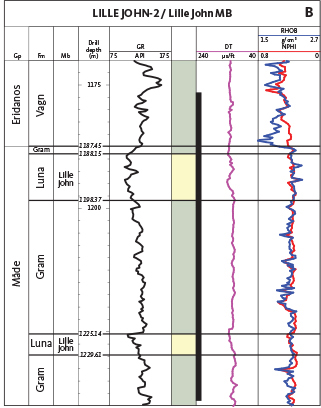

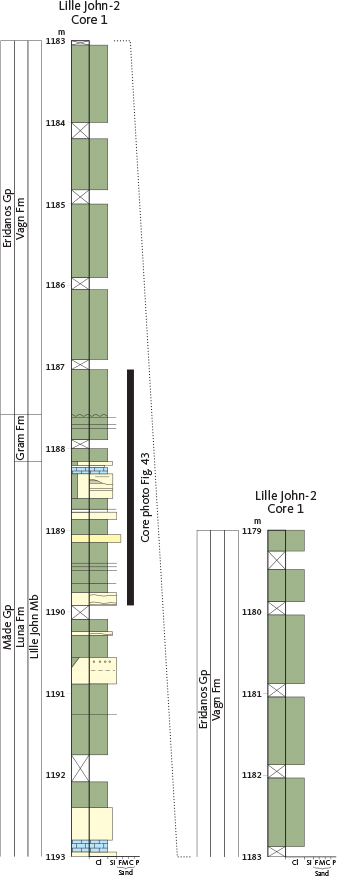

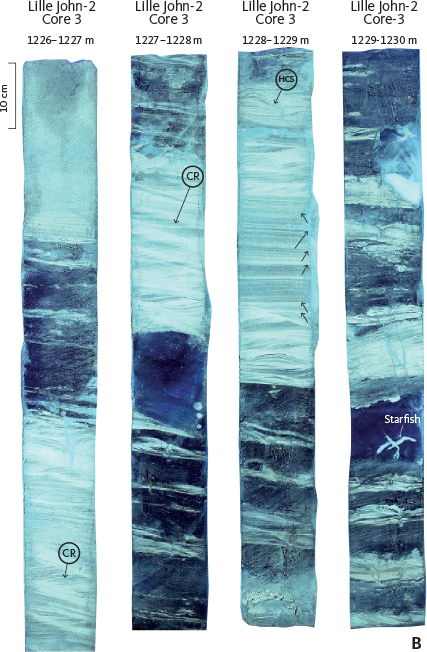

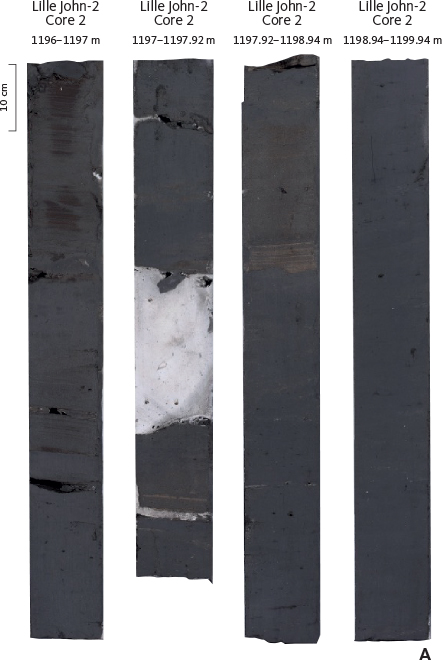

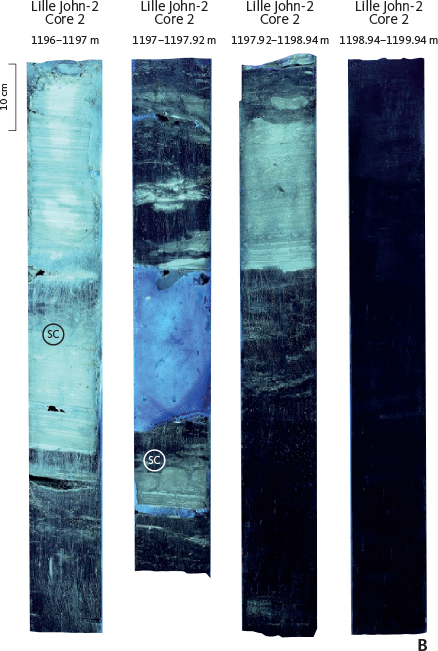

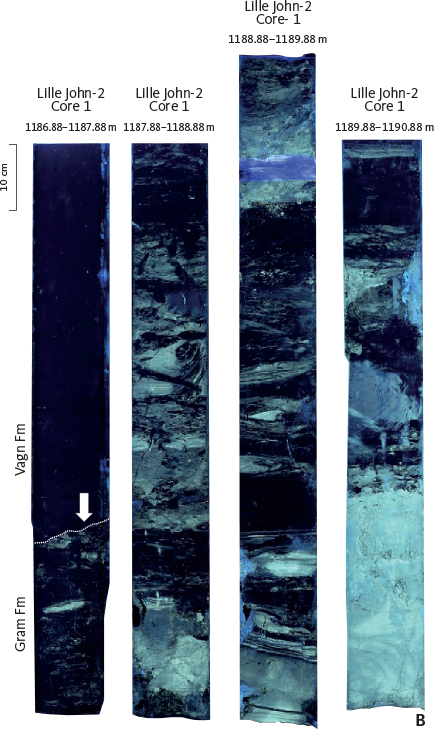

The lithological and sedimentological interpretations in the present study are based on well and borehole data from onshore and offshore Denmark. Most of these data are based on ditch cuttings samples, but a few sections from North Sea wells have been cored: Dany-1 (1429.95–1421.90 m), E-8 (1266–1249.70 m), Lille John-2 (1249.70–1179 m). Onshore, in the westernmost part of Denmark, the entire borehole of Sdr. Vium (0–282 m) has been cored. Cuttings from selected wells and boreholes have been described under a binocular microscope. Cored sections have been measured and described. Core photos and advanced photo processing techniques have supported the descriptive process.

4.2 Biostratigraphy

As outlined above, only few, stratigraphically very restricted cored sections exist from the Miocene–Pliocene in the Danish North Sea sector. Biostratigraphic data from a cored section in the E-8 well representing the upper Langhian – lower Serravallian (Middle Miocene; Quante & Dybkjær 2018) and from a core in the Lille John-2 well representing the uppermost Tortonian –lowermost Zanclean (Upper Miocene – lowermost Pliocene; Sheldon & Dybkjær 2015) are included here. No macrofossils have been described from these cores.

Fortunately, a new comprehensive multidisciplinary microfossil study (Sheldon et al. 2025) on core samples covering most of the Lower and Middle Miocene succession in the Valhall–Hod area in the southernmost Norwegian North Sea sector has provided a solid age relationship for the new Danish lithostratigraphic units as these are readily identified in the Norwegian wells.

Data from the cored onshore borehole Sdr. Vium were used for correlating between the onshore and offshore sections (Kellner et al. 2025). The fossil content in the onshore Denmark lithostratigraphic units is described in Rasmussen et al. (2010).

A number of microfossil groups, including dinocysts, foraminifera, nannofossils and diatoms, have been analysed from wells in the Danish offshore North Sea sector and used to date the Neogene succession and to guide correlations. However, only minor parts of these studies have been published and the majority of these are based on dinocyst stratigraphy. The published biostratigraphic studies are outlined in the following.

King (1983, 1989) studied the foraminifera assemblages in a number of offshore wells in the North Sea, including the Danish R-1, S-1 and U-1 wells, and defined a zonation scheme that has subsequently been widely used. In the sequence stratigraphic study of Michelsen et al. (1998), biozonations are presented for a number of Danish North Sea wells. The biostratigraphy is mainly based on foraminifera, while nannoplankton and dinocysts are included in a few wells. Laursen & Kristoffersen (1999) presented a detailed study of the foraminifera assemblages in the Danish onshore Miocene lithostratigraphic units as defined at that time.

Schiøler (2005) presented a detailed study of dinocysts in the Oligocene – Lower Miocene succession in the Alma-1 well and identified a series of last occurrences of dinocysts and acritarchs with potential for a detailed subdivision of the succession. In a subsequent study by Schiøler et al. (2007), unpublished biostratigraphic data from 29 wells were re-assessed, and new data from 11 additional wells were produced for that study. The results are presented as biostratigraphic events and biozonations, and correlated with the chronostratigraphy and with the Palaeogene – Middle Miocene lithostratigraphic units defined in the study.

The dinocyst stratigraphy of the Oligocene–Miocene boundary section in the Frida-1 well was studied by Dybkjær & Rasmussen (2007). In a later study by Dybkjær et al. (2012) that includes dinocysts, foraminifera and nannofossils, the succession was correlated in detail with the Italian Stratotype Section and Point for the base of the Miocene. The dinocyst zonation of Dybkjær & Piasecki (2010) was defined based on analysis of more than 2000 sediment samples from outcrops and more than 50 wells/boreholes, most of which were drilled onshore Denmark. However, data from four offshore wells (Frida-1, Lone-1, S-1 and Tove-1) were also included in the definition of this zonation. Quante & Dybkjær (2018) presented a study of the dinocyst assemblage in a cored section covering the upper Langhian – lower Serravallian (Middle Miocene) in the E-8 well. Dybkjær et al. (2021) presented dinocyst data from three Danish North Sea wells (Nora-1, Tove-1 and Vagn-2) and illustrated the applicability of the dinocyst zonation of Dybkjær & Piasecki (2010) in a larger area. Based on a combination of the dinocyst zonation and seismic data, a robust stratigraphic framework for the Neogene succession offshore Denmark was established. This framework was also applied to provide a more precise dating of the Norwegian Molo Formation, located on the continental shelf in the eastern Norwegian Sea than was previously possible.

The most recent biostratigraphic study is that by Sheldon et al. (2025), a comprehensive study that includes a multidisciplinary study of the Miocene succession in six wells located in the Valhall–Hod area in the southernmost Norwegian North Sea. In addition to this literature, biostratigraphic data from several unpublished studies are included in the data set used here.

The chronostratigraphy of the formations, as presented in this monograph, are mainly based on dinocyst stratigraphy, but are supported by data from the other microfossil groups. Furthermore, the variations in the microfossil assemblages have provided information about changes in the depositional environment, for example water depths, salinity and sea-surface temperatures.

The biozonations identified in the lithostratigraphic units, as outlined in the following for each unit, comprise the North Sea foraminifera zonation, NSB (North Sea Benthic) of King (1983, 1989), the more proximal foraminifera zonation of Laursen & Kristoffersen (1999), the dinocyst zonation of Dybkjær & Piasecki (2010) and the composite North Sea (NS-) zonation (including agglutinating, calcareous benthic and planktonic foraminifera) of King (2016). Correlation between these zonations and with the global nannofossil zonation of Martini (1971) is presented (Fig 9.), in addition to correlation of the new Neogene lithostratigraphy defined in this study with the dinocyst zonation of Dybkjær & Piasecki (2010; Fig. 1). The dinocyst zonation of Dybkjær & Piasecki (2010) was correlated with the Geological Timescale of Gradstein et al. (2004) but has in Fig. 9 been calibrated to the Neogene Geological Timescale of Raffi et al. (2020). Dinocyst taxonomy follows Fensome et al. (2019).

Fig. 9 Dinocyst zonation and foraminifera zonations for the Miocene and Pliocene succession offshore Denmark. Modified from Dybkjær & Piasecki (2010) and King (2016). The chronostratigraphy is based on the cited sources. The ages of the stage boundaries in the dinocyst zonation are from Raffi et al. (2020) combined with Turco et al. (2024). The correlation of benthic foraminifera zones for the North Sea (King 1989) and onshore Denmark is from Laursen & Kristoffersen (1999).

It has also been attempted to describe the general abundance and diversity of the microfossil groups for each lithostratigraphic unit. However, it is important to note that each unit is often only represented by a few wells and that these wells are not necessarily representative for all of the Danish North Sea area. The abundance and diversity of the microfossil groups often varies from proximally to distally located settings due to changes in factors such as water depth, salinity and nutrient supply. In addition, depositional and post-depositional effects, such as sorting due to variations in energy-level and dissolution of calcareous microfossils, may influence the abundance and diversity of the microfossils. Therefore, the descriptions of the microfossil content should be seen as a generalised picture based on a restricted database.

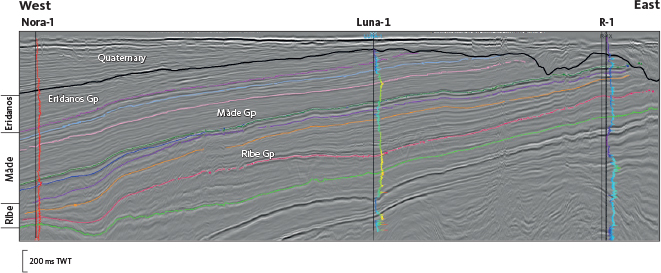

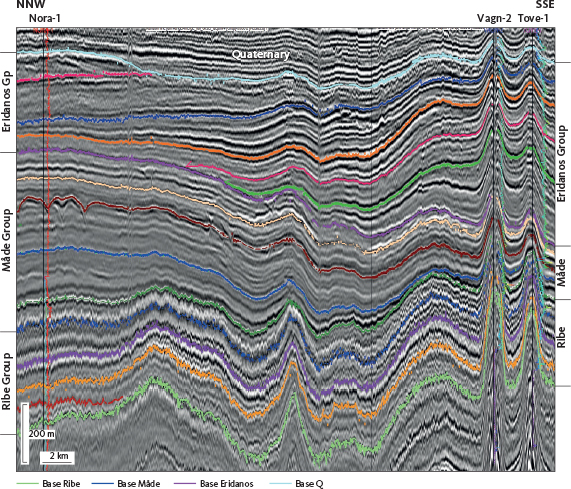

4.3 Seismic data

The seismic study is based on multichannel 2D data: Da94, -95, -96; GR97, -98; UGCE-96/97; NP-85; CGD-85; NDBT-94; HG-97; DK13; PSEUDO-3D-2013 and the merged Angelina-MRD2010 3D survey (Fig. 2B). The seismic data are processed in reverse polarity using a zero-phase wavelet, where a hard kick represents a negative (black) reflection (trough), and a soft kick represents a positive (white) reflection (peak). The seismic interpretation was conducted on both Landmark and Petrel workstation systems. Stratigraphic surfaces separating different seismic facies, commonly the maximum regressive surface, have been mapped regionally. In addition, selected surfaces representing marked unconformities, either local or regional, and surfaces characterised by marked amplitude anomalies are also mapped. On the 3D survey, horizons of special interest were tracked manually every 10 inlines and subsequently auto-tracked. This was followed by extraction of seismic attributes, for example RMS (root mean square) attributes in the Petrel software packet.

4.4 Petrophysics

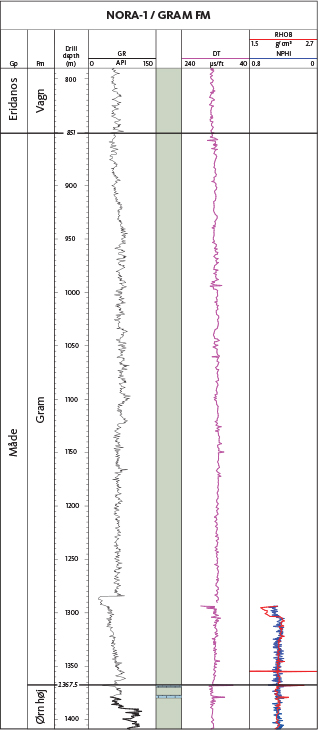

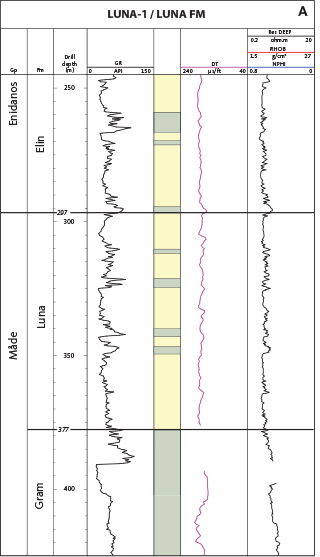

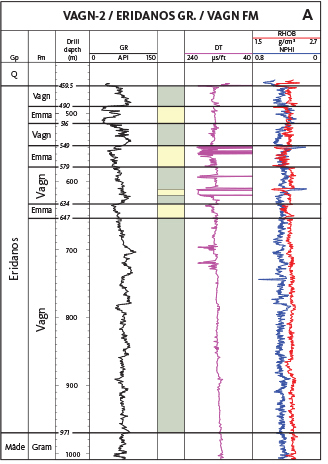

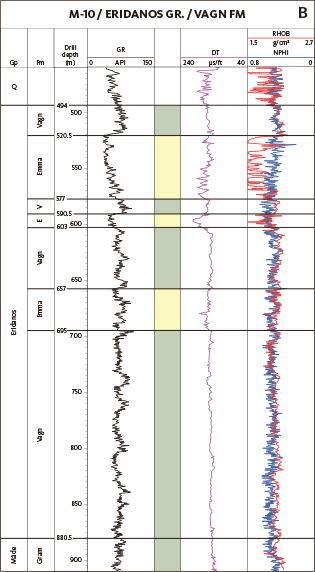

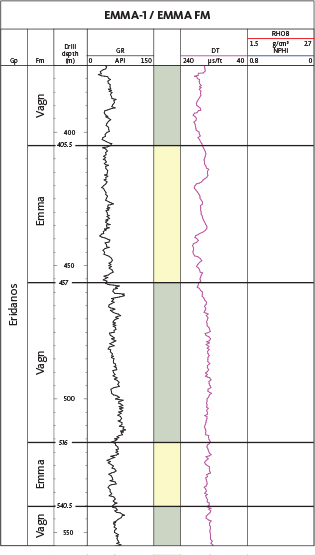

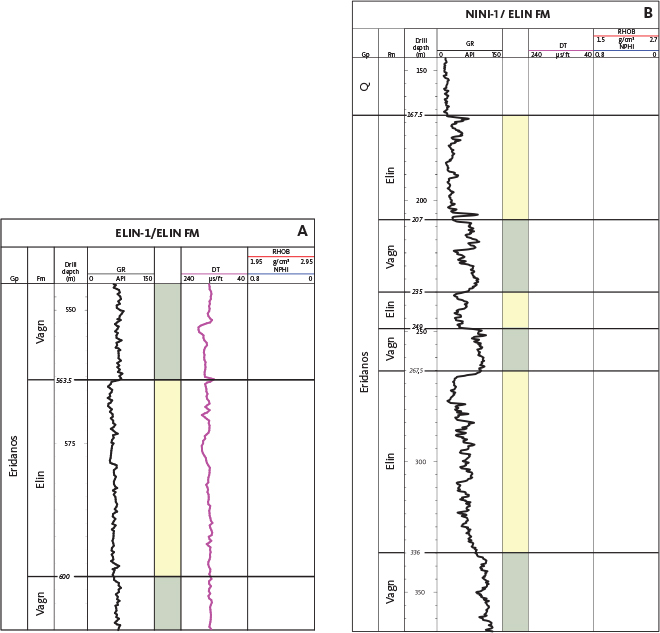

The logs plotted for each of the wells in Plates 1–12 (Supplementary Files) are the gamma-ray and sonic-log readings, together with the bulk density and neutron porosity plotted together. The sonic curve is available in all the wells for the whole sequence from the base of the Dany Formation to the top of the Vagn Formation.

The bulk density and neutron porosity logs are only available in the lower part of the succession because the wells were drilled in two sections/steps. The top part is the 16-inch hole down to about 1219 m (4000 ft) bKB (below Kelly Bushing) just above the top of the overpressured shale in the lower part of the Gram Formation, using seawater and bentonite mud. The next part involves drilling a 12.25-inch hole into the underlying overpressured formations using heavier mud. The shift can be seen in Karl-1 (Supplementary Files, Plate 1) where the gamma-ray log shows a gap just around 1219 m (4000 ft) bKB. Due to the large hole size in the upper part of the succession, the bulk density and the neutron logs are seldom run because of the difficulty of obtaining good contact with the formation required by these logging tools.

4.5 Palaeobathymetry

The construction of seascape topography (bathymetry; Fig. 10) is based on the following steps: (1) Extrapolation of palaeo-sealevel from delta plain gradient/relief assuming a very low relief/gradient. (2) Add the water depth at the shelf break, here assumed to be in the order of 100–150 m supported by biofacies. (3) Add the thickness of the slope deposits (equal to the height of the slope clinoforms) based on isochore maps.

Fig. 10 Conceptual figure showing the key parameters used in reconstructing palaeobathymetry: water depth, based on biofacies; isochore thickness of clinoforms.

5 Lithostratigraphy

5.1 Introduction to the lithostratigraphic subdivision

The Neogene succession of the North Sea has traditionally been subdivided into two groups separated by a regionally mappable seismic reflector/unconformity commonly referred to as the ‘mid-Miocene Unconformity’ (MMU; Deegan & Scull 1977; Hardt et al. 1989; Knox & Holloway 1992; Schiøler et al. 2007). However, there is some confusion about the age and origin of this surface. In some parts of the North Sea, this reflector represents a hiatus in the sedimentary record, especially in UK, German and Dutch waters and in the northern part of the Norwegian sector of the North Sea. In other parts of the North Sea, including the Danish sector, this reflector represents a distinct intra-Langhian flooding surface identified by a marked lithological change but without any detectable regional hiatus (Dybkjær & Piasecki 2010; Rasmussen & Dybkjær 2014), with the exception of local breaks or onlap at topographic highs such as salt structures.

In the UK, the section below the MMU, which covers the Oligocene – Middle Miocene, is named the Westray Group (Knox & Holloway 1992), whereas in Norway the Miocene succession below this surface is included in the Hordaland Group (Deegan & Scull 1977; Hardt et al. 1989; Eidvin et al. 2014a). In the Dutch sector, an unconformity is also reported in the middle part of the Miocene and referred to the so-called MMU, but the unconformity is placed somewhat higher, at the base of the Upper Miocene; the section below the ‘MMU’ is referred to the Groote Heide and Veldhoven Formations (Munsterman et al. 2019).

Another even more distinct boundary is found at the base of the Miocene both offshore and onshore Denmark. This boundary was used by Rasmussen et al. (2010) to define the base of the Ribe Group in onshore Denmark. In the present study we have followed this approach for the offshore sector, referring the succession from the basal Miocene unconformity separating the Oligocene Brejning Formation from the Miocene mud-rich deposits up to the MMU/mid-Miocene regional flooding surface to the Ribe Group. Both the basal Miocene lower boundary and the mid-Miocene upper boundary of the Ribe Group are prominent seismic reflectors (‘hard kicks’; Rasmussen et al. 2005).

In the UK and Norwegian sectors, the succession above the so-called mid-Miocene unconformity is referred to the Nordland Group (Deegan & Scull 1977; Hardt et al. 1989; Knox & Holloway 1992). Schiøler et al. (2007) also provisionally adopted this group in the Danish North Sea, but the focus of their study was the Palaeogene, and the Nordland Group was not subdivided lithostratigraphically. Note that the location of the base Nordland Group in their fig. 2 (top of the Hodde Formation) is inconsistent with that shown in their correlation panels, where this boundary (= TL, Top Lark) is indicated at the base of the Hodde Formation as recognised here (see also Dybkjær et al. 2021).

As some of the lithostratigraphic units defined onshore Denmark can be readily traced westwards into the offshore area, and the terminology has indeed been applied during drilling operations in the North Sea, the onshore Måde Group, representing the upper Middle Miocene to Upper Miocene succession, is in this study also adopted in the Danish offshore sector; use of the Nordland Group is thus discontinued in the Danish sector. The sediments referred to this group are dominated by marine, hemipelagic clay.

During the Pliocene, a new siliciclastic system began to fill the southern North Sea Basin. This system is known as the Baltic River system (Bijlsma 1981) or the Eridanos Delta (Overeem et al. 2001). During most of the Pliocene, sediments from this delta system were deposited in the Danish sector, and the Danish offshore Pliocene succession is thus referred to as the Eridanos Group.

The new lithostratigraphy of the Neogene succession offshore Denmark (Fig. 1) is here formally established and generally follows the guidelines of Salvador (1994). A major challenge in the definition of lithological units and boundaries is the scarcity of cores and the incomplete petrophysical coverage of the Middle to Upper Miocene and Pliocene successions. Most of the Miocene units are adopted from the onshore lithostratigraphy as there is a one-to-one correlation from onshore to offshore seismic data and no marked changes in lithology. Six new lithostratigraphic formations and one new member are erected (Fig. 1). Offshore, the Ribe Group comprises the Klintinghoved, Bastrup, Arnum, Odderup, Dany (new) and Nora (new) Formations. The Måde Group consists of the Hodde, Ørnhøj, Gram, Marbæk, and Luna (new) Formations. The Luna Formation includes the Lille John Member (new). The Eridanos Group is composed of the Vagn (new), Emma (new) and Elin (new) Formations.

5.2 Onshore–offshore correlation

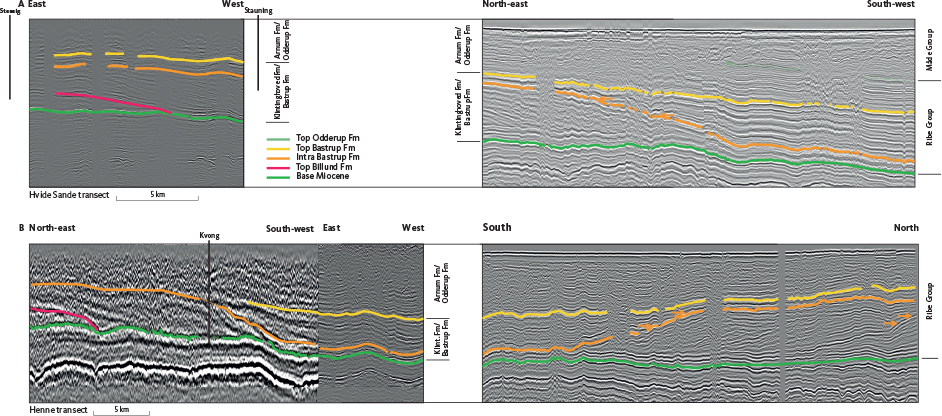

Correlation between the onshore and offshore Neogene successions, within the lithostratigraphic framework of Rasmussen et al. (2010), is provided by two transects crossing the Danish west coast (Fig. 11). The main challenge in this operation is the offset of seismic data along the Danish coast, which is 16 km at the transect at Stauning (Figs 2, 11A) and 6 km at Henne Beach (Figs 2, 11B). Nevertheless, the seismic boundaries and facies can be traced with confidence across this transition between the onshore and offshore data (Fig. 11).

Fig. 11 Two seismic composite sections across the onshore–offshore area in Denmark showing the overall architecture of the Neogene (Miocene) succession onshore and in the easternmost offshore area, the Ringkøbing–Fyn High area. Note how the progradational and aggradational packages can be recognised across the shoreline. The locations of the cross-sections are shown in Fig. 2B.

The base Miocene boundary, which is characterised by a strong, continuous reflector, is readily recognised on both onshore and offshore data. The lowermost Miocene Vejle Fjord and Billund Formations (Rasmussen et al. 2010) are absent or very thin in the offshore realm. The pinch-out of these lowermost Lower Miocene deposits is seen on the Hvide Sande and Kvong transects (Figs 2, 11) and is confirmed by the Kvong borehole, which provided the biostratigraphic evidence.

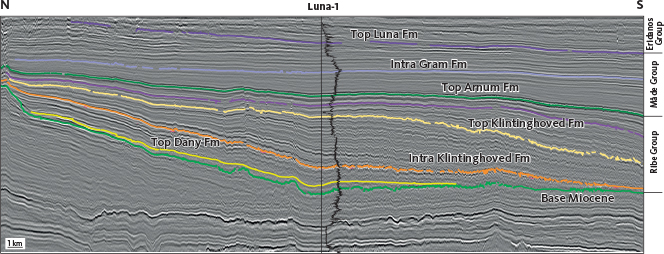

The Klintinghoved and Bastrup Formations interfinger. A significant part of the succession comprising the Bastrup Formation is characterised by clinoformal seismic reflection pattern (Fig. 11). Laterally, west and south-westwards, this facies is succeeded by a seismic facies displaying a parallel to sub-parallel reflection pattern, which shows onlap on to the clinoformal package. This parallel to sub-parallel facies is in the North Sea realm dominated by mud, as indicated by the tie with the Luna-1 well (Fig. 12; Supplementary Files, Plate 4) and is referred to the Klintinghoved Formation. These two seismic facies are in turn succeeded upwards by a parallel reflection pattern of regional extent (e.g. Fig. 11). On the northern part of Fig. 11A, this parallel seismic pattern ties with the Stensig and Stauning boreholes. A strong reflector, forming the base of the seismic facies correlates with the top of the aforementioned lower clinoformal package, which formed the top of the lower sand unit of the Bastrup Formation in the Stensig and Stauning boreholes. A second strong reflector correlates with the base of the upper Bastrup Formation sand unit in the two boreholes, and the third reflector correlates with the top of the upper sand unit (top Bastrup Formation; Fig. 11). This upper part of the Bastrup Formation, which is characterised by a parallel reflection pattern, grades westward into the North Sea into more muddy deposits, representing a lateral interfingering with the Klintinghoved Formation.

Fig. 12 N–S-trending geo-section tying the Luna-1 well in the Ringkøbing–Fyn High area.

The Arnum Formation succeeds the Bastrup and Klintinghoved Formations (Figs 1, 11, 12). This formation is expressed seismically by a parallel to sub-parallel reflection pattern, both onshore and offshore (Figs 11, 12). However, in the onshore parts of the Henne and Hvide Sande transects on Fig. 11 (see location of the transects on Fig. 2), the reflection pattern is obscured, partly due to the vintage nature of the data and partly due to poor seismic resolution in the shallow portion of the seismic data. The upper part of the Arnum Formation interfingers with the Odderup Formation. On the Ringkøbing–Fyn High, some sandy intervals correlative with the Odderup Formation have been drilled in the Luna-1 and R-1 wells.

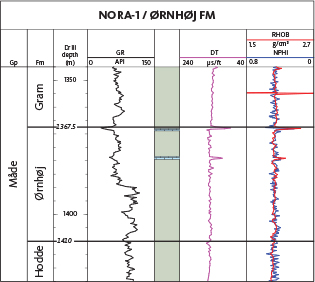

The top of the Arnum Formation is characterised by a very distinct, continuous and high amplitude seismic reflector (Figs 11, 12). This boundary represents a major lithological change in the entire North Sea Basin (Rasmussen et al. 2010; Rasmussen & Dybkjær 2014). Onshore and in the eastern part of the offshore realm, the boundary represents a change from sandy and muddy sediments to muddy clay and clayey, glauconitic deposits. These fine-grained deposits correspond to the Hodde and Ørnhøj Formations (Rasmussen et al. 2010). These formations have not been detected seismically on onshore data, but offshore, they are characterised by a parallel reflection pattern.

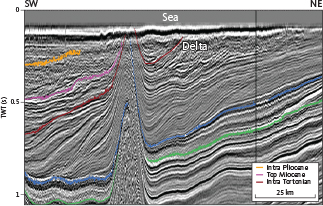

The succeeding Gram Formation is thin in the onshore area, being less than 25 m in most places, and is thus not detectable on seismic data. However, in the offshore realm, the formation is up to 200 m thick (e.g. Luna-1 well; Fig. 12). Sand units intercalated in the Gram Formation are referred to the Marbæk Formation; this formation is difficult to distinguish on seismic data in the eastern part of the study area, but a clinoformal package recognised SW of the Danish west coast (Fig. 13) is correlated with the Marbæk Formation. The marked change in thickness of the Gram and Marbæk Formations from offshore to onshore is due to truncation of the formations associated with Quaternary uplift and glacial erosion (Japsen et al. 2010); the Gram and Marbæk Formations are the youngest Neogene deposits onshore Denmark (Rasmussen et al. 2010).

Fig. 13 Clinoformal package interpreted as a distal part of the Marbæk Formation. Modified from Japsen et al. (2007).

Fig. 14 Legend applicable to all cores and well logs shown in this study.

6 Updated and revised Neogene lithostratigraphy

6.1 Ribe Group

revised group

History. The Ribe Group was erected by Rasmussen et al. (2010) to include the mainly deltaic Lower Miocene formations of onshore Denmark. The group is extended here to include the wider Danish North Sea region, including the Central Graben, with the addition of two new formations, the Dany and Nora Formations.

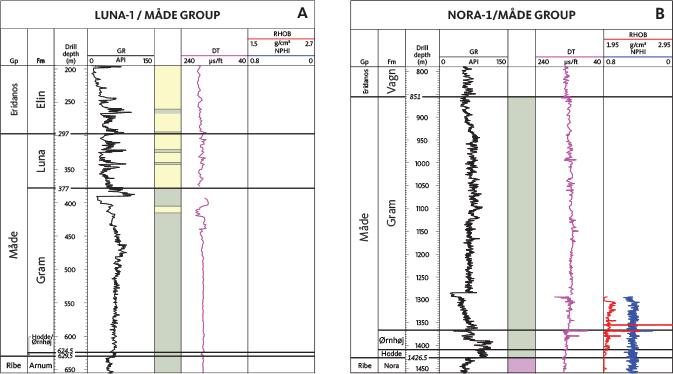

Name. After the town of Ribe, southern Jylland (Fig. 2).

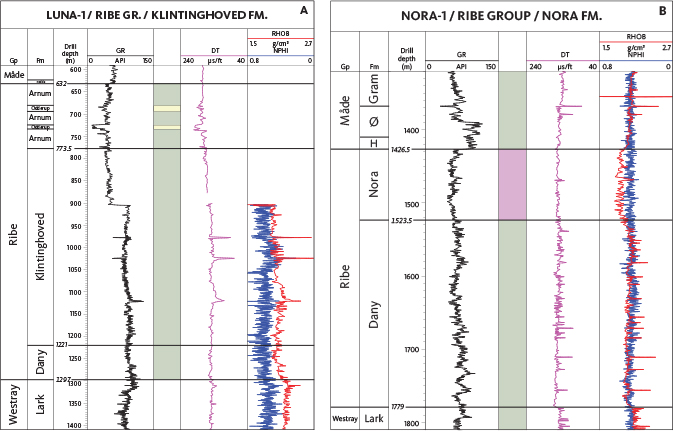

Type area. The type area is in central and east Jylland where both fluvial and marine sand and mud are exposed at several localities. The Store Vorslunde well (DGU no. 104.2325) displays a complete section from 219 to 1 m measured depth (MD; Rasmussen et al. 2010, their fig. 17. Representative North Sea wells in which the Ribe Group is well-developed are the Luna-1 well (56˚05′57″N, 5˚52′53″E) from 1297 to 632 m MD and the Nora-1 well (55˚58′09.17″N, 04˚24′04.46″E) from 1779 to 1426.5 m MD (Figs 15A, B).

Fig. 15 The Ribe Group onshore is best represented by the St. Vorslunde borehole (see Rasmussen et al. 2010). The offshore development of the Ribe Group is displayed by the Luna-1 well on the Ringkøbing–Fyn High (A) and the Nora-1 well in a distal setting (B). In Luna-1, the Ribe Group is represented from 1297 to 632 m MD and in Nora-1 from 1779 to 1426.5 m MD. The Luna-1 well is the reference well for the Klintinghoved Formation, from 1221 to 773.5 m MD (A). The displacement of the log (log break) at ca. 900 m is an artifact due to casing. The type section for the Nora Formation is the Nora-1 well from 1523.5 to 1426.5 m MD (B). H: Hodde Formation. Ø: Ørnhøj Formation. Petrophysical logs: GR, gamma-ray; DT, sonic; RHOB, density; NPHI, neutron porosity. For legend, see Fig. 14.

Thickness. From c. 200 m to 300 m over most of the Danish sector with a maximum of c. 600 m recorded in the Cleo-1 and Luna-1 wells (Supplementary Files, Plates 1–9).

Lithology. Onshore and on the Ringkøbing–Fyn High, the group is composed of cyclic deltaic gravel, sand and mud. The sand and gravel consist mainly of quartz, flint, quartzite and some mica grains. The micaceous mud is homogenous with some intercalations of laminated fine-grained sand. The clay mineral assemblage is dominated by kaolinite and illite (Nielsen et al. 2015); gibbsite is also a common mineral of the fine-grained fraction. Coal beds are common onshore. In the most distal setting (i.e. the Central Graben), bioturbated mud and diatomite-rich deposits dominate, the latter becoming prominent in the upper part of the group.

Log characteristic. The gamma-ray log typically shows a highly serrated pattern and an overall decreasing gamma-ray response upwards. This decreasing trend can be seen in a number of intervals, but overall, there are three such intervals that reflect progradation of successive delta lobes of the Bastrup and Odderup Formations. In general, the neutron-density logs are superimposed, but in the Nora Formation, a distinct crossover is characteristic.

Fossils. Both the dinocyst and foraminifera assemblages are generally of low abundance and diversity in the lowermost part of the Ribe Group, possibly reflecting low salinity conditions and a restricted basin. Faunal/floral abundance and diversity increase upwards reflecting the establishment of more open marine conditions. Distinct variations are also seen between the marine clay-dominated units and the fluvio-deltaic sand-dominated units with the highest abundance and diversity of microfossils in the marine clay-dominated units. More detailed descriptions of the microfossil assemblages are given below in the definitions of the formations.

Depositional environment. The Ribe Group comprises sediments deposited during the progradation of three successive delta systems from the north towards the south. The main deltas were located across Jylland and on the eastern part of the Ringkøbing–Fyn High area (Hansen & Rasmussen 2008; Rasmussen et al. 2010). Sand-rich facies were deposited on the delta platform slope and in shoreface environments associated with barrier island complexes, mainly east of the main delta front. Mud was transported westwards by an anticlockwise gyre and deposited as contourites on the slope and shelf area west of the main delta. In the basin floor environment, hemipelagic mud and diatomite were deposited in estimated water depths of c. 700 m. Diatomites dominated the upper part of the group in the westernmost portion of the Danish sector.

Boundaries. The lower boundary is normally sharp and marked by a change from greenish, glaucony-rich clay to dark brown mud (Larsen & Dinesen 1959; Rasmussen et al. 2010). The glaucony-rich clay is onshore referred to the Brejning Formation and offshore to the Lark 3 unit (see Schiøler et al. 2007), while the dark brown mud onshore is referred to the Vejle Fjord Formation and offshore to the Dany Formation. On the Ringkøbing–Fyn High, there is a gap in sedimentation at this boundary. This results in deposition of Klintinghoved Formation on top of Oligocene clay. Locally, for example in the C-1 well and at the Dykær locality, a gravel layer is present representing this unconformity (Rasmussen et al. 2010). The lower boundary is subtle offshore, in contrast, being characterised by a change from dark, greenish grey mud to brown or yellowish-brown mud (Schiøler et al. 2007), especially in the westernmost part of the Ringkøbing–Fyn High and within the Central Graben area. Despite this change in lithological character from onshore to offshore, the boundary is still very distinct on seismic data. The sediments below the boundary are more consolidated, which gives rise to a prominent positive seismic reflector at the boundary. This shift in consolidation is also seen as an amalgamation in the neutron-density log (Supplementary Files, Plates 1–9). On gamma-ray logs, the base of a marked upward decrease in gamma-ray response is found at the boundary in many wells (Supplementary Files, Plates 1–11).

The upper boundary is characterised by a distinct change from sand-rich sediments to mud in the eastern part of the study area; elsewhere, over most of the Danish sector, it is defined by a marked change from brown mud, with some interbedded fine-grained sand layers, to dark brown mud or greenish, glaucony-rich clay. In most places, there is a very distinct upward increase in gamma-ray readings across the boundary; only wells in the Ringkøbing–Fyn High area (e.g. the Luna-1 and Nini-1 wells) show a more subdued increase in the gamma-ray response (Figs 15A, B; Supplementary Files, Plates 1–9).

Distribution. The Ribe Group is recognised over most of the Danish area but is truncated in the north-eastern part of central Jylland and north Jylland.

Geological age. The Ribe Group is of Aquitanian–Langhian (Early Miocene – early Middle Miocene) age.

Subdivision. The group is subdivided into a total of eight formations (Fig. 1). The two lower formations, the Vejle Fjord and Billund Formations, are not present in any wells in the Danish North Sea, but seismic data indicate that they are present in the extreme eastern part of the offshore area. These two formations are not considered further here. Relevant for this study are the Klintinghoved, Bastrup, Odderup, Arnum, Dany (new) and Nora (new) Formations.

6.1.1 Klintinghoved Formation

revised formation

History. The Klintinghoved Formation, which is a fossil-rich mud deposit (Fig. 16A), was defined by Sorgenfrei (1940). The formation was included in the first Miocene lithostratigraphic scheme of Rasmussen (1961).

Fig. 16 (A): The best outcrop section of the Klintinghoved Formation is at Hostrup, north-west Jylland, where a 7 m thick section of mica-rich mud is exposed along a 100 m long coastal cliff. Height of the cliff is 6 m; dashed white line indicates the boundary between the Klintinghoved Formation and Quaternary sediments. (B): The Bastrup Formation crops out at Tandskov north of Silkeborg where fluvial sand and gravel forms an approximately 10 m high section; dashed white line indicates the boundary between the Bastrup Formation and Quaternary sediments.

Name. After Klintinghoved cliff at Flensborg Fjord (Fig. 2).

Type and reference sections. The type section is the outcrop at Klintinghoved cliff (54 ˚53′23.15″N, 9 ˚49′43.62″E (Rasmussen et al. 2010, fig. 40). The North Sea reference well is the Luna-1 well (56 ˚05′57″N, 5˚52′53″E) from 1221 to 773.5 m MD (Fig. 15A).

Thickness. Onshore, the thickness of the formation ranges up to c. 125 m. The formation is progressively truncated towards the east and north-east. In the North Sea realm, thicknesses up to 460 m are common. Westwards, the Klintinghoved Formation interfingers with the Dany Formation.

Lithology. The formation consists of dark brown mud with intercalated laminated sand beds or thin homogenous fine-grained sand layers (Fig. 16A; see also Rasmussen et al. 2010). The clay mineralogy is dominated by kaolinite and illite, in equal proportions, and minor smectite (up to 10%; Nielsen et al. 2015).

Log characteristics. The Klintinghoved Formation is characterised by moderate to high gamma-ray values. The log pattern is serrated due to the alternation of sand- and mud-rich deposits (Fig. 15A); a general stacking of intervals showing upward decreasing gamma-ray values (Fig. 15A, Luna-1, 1215–1150 m; 1140–1040 m; 875–773.5 m) reflects progradation and lobe switching of the delta system.

Fossils. The Klintinghoved Formation contains a moderately rich and diverse dinocyst assemblage (Dybkjær & Rasmussen 2007; Dybkjær et al. 2012; Rasmussen et al. 2015). Calcareous benthic and planktonic foraminifera are rare in the lowermost part of the formation while agglutinating foraminifera occur frequently. In the upper part, calcareous benthic foraminifera increase in abundance and diversity, planktonic foraminifera are present, and agglutinating foraminifera are rare. Diatoms and sponge spicules are present throughout the formation. Radiolaria are rare (King 1973; Laursen et al. 1992; Dybkjær et al. 2012; Rasmussen et al. 2015).

Depositional environment. The Klintinghoved Formation in the North Sea area was laid down below fair-weather wave base in front of the prograding delta and shoreface system of the Bastrup Formation and in the inner to outer shelf environment, mainly as contourites. The depositional environment was dominated by storm and tidal processes and currents formed by an anticlockwise gyre in the North Sea.

Boundaries. In the onshore and eastern part of the Ringkøbing–Fyn High area, the lower boundary of the Klintinghoved Formation is characterised by a sharp change in lithology from white to grey sand of the Billund Formation to dark brown mud of the Klintinghoved Formation (Rasmussen et al. 2010). The boundary may also be expressed by a sharp-based gravel layer, the base of which forms the boundary; the clasts of the gravel layer may be up to 5 cm in diameter (Rasmussen & Dybkjær 2020). In distal settings, the lower boundary is expressed by a change from dark brown mud with intercalated silt and fine-grained sand beds of the Bastrup Formation to mud-dominated sediments of the Klintinghoved Formation. On the gamma-ray log, this is recorded by a distinct increase in gamma-ray values. In regions with a more gradual change in sediment character, the gamma-ray readings are more gradational from slightly decreasing to increasing (Fig. 15A).

In the onshore and eastern part of the Ringkøbing–Fyn High area, the upper boundary of the Klintinghoved Formation is, by definition, characterised by the first significant sand interval of the Bastrup Formation, consisting of a sand unit at least 5 m thick, in which the sand to mud ratio is greater than 75%. In the more distal settings, the Klintinghoved Formation is overlain by the Arnum Formation; the boundary is characterised by a change from brown mud-dominated sediments with interbeds of greyish silt and fine-grained sand to dark brown mud and locally a glaucony-rich band, the base of which forms the boundary. On the gamma-ray log, the transition towards the Bastrup Formation is subtle, but towards the Arnum Formation, the upper boundary is often recorded as a weak increase in gamma-ray values (Fig. 15A).

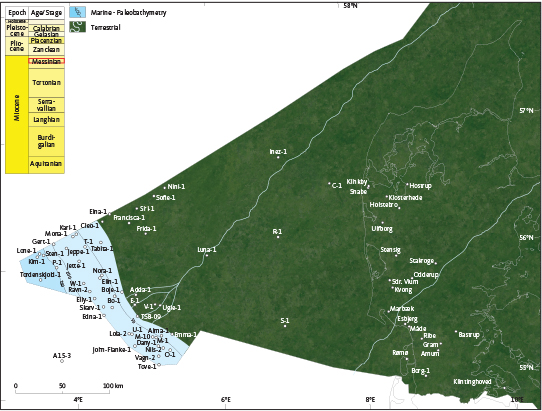

Distribution. The formation is present in southern, central and western Jylland and in the entire Ringkøbing–Fyn High area of the North Sea (Fig. 17). In the western part of the Danish sector, in the Central Graben, the formation interfingers with the Dany Formation (e.g. Supplementary Files, Plate 4).

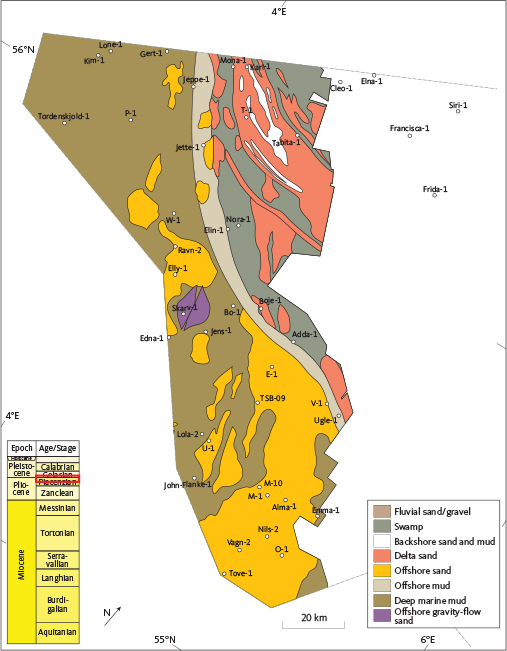

Fig. 17 Distribution of the Klintinghoved, Bastrup and Dany Formations (stratigraphic interval indicated by red box) illustrated in terms of their dominant sedimentary associations: the floodplain sediment and the channel-, delta- and shoreface sand are referred to the Bastrup Formation; the offshore mud is referred to the Klintinghoved Formation; the slope mud and deep marine mud are referred to the Dany Formation. Neogene deposits of this age have been removed by erosion east of the truncation line indicated in the offshore area; the distribution of sedimentary associations east of this line (and north-east of the onshore outcrops/wells) is hypothetical. The striped belts indicate areas that are inferred to have experienced shifting depositional settings during the late Aquitanian – early Burdigalian.

Biostratigraphy. The following dinocyst zones: the Caligodinium amiculum Zone, the Thalassiphora pelagica Zone, the Sumatradinium hamulatum Zone and the lower part of the Cordosphaeridium cantharellus Zone of Dybkjær & Piasecki (2010) have been documented in the Klintinghoved Formation in the Frida-1 well (Dybkjær & Rasmussen 2007; Dybkjær et al. 2012) and the Luna-1 well (Figs 1, 9; Rasmussen et al. 2015).

The calcareous benthic foraminifera zones recorded from the formation include the upper part of NSB9–NSB10I (Laursen & Kristoffersen 1999; Rasmussen et al. 2015). In addition, the composite zones NS34 (upper part) – NS35b (King 2016) are reported from the Klintinghoved Formation in the Frida-1 well (Fig. 9; Rasmussen et al. 2015).

Geological age. The Klintinghoved Formation comprises deposits of late Aquitanian to mid-Burdigalian (Early Miocene) age.

6.1.2 Bastrup Formation

History. The formation was erected by Rasmussen et al. (2010) as part of a major revision of the Miocene lithostratigraphy covering onshore Denmark. The previous lithostratigraphy of Rasmussen (1961) encompassed only two sand-rich units, but during the intense drilling campaign from 2000 to 2010, it became clear that the Miocene succession was formed by three discrete deltaic successions, and revision was therefore necessary.

Name. The Bastrup Formation is named after the village of Bastrup in southern Jylland (Fig. 2).

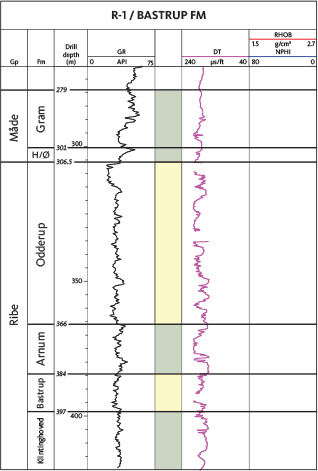

Type and reference section. The type section is the interval from 108 to 84 m MD in the Bastrup borehole (DGU no. 133.1298; 55˚24′21.58″N, 9˚14′47.40″E; Rasmussen et al. 2010, fig. 52). The North Sea reference section is the interval from 397 to 384 m MD, in the borehole R-1 (Fig. 18).

Fig. 18 The North Sea reference section of the Bastrup Formation is the R-1 well, from 397 to 384 m MD. H/Ø: Hodde/Ørnhøj Formations. For legend, see Fig. 14.

Lithology. Onshore, the formation consists of grey, medium- to coarse-grained sand with some gravel (Fig. 16B). The diameter of individual pebbles in gravel beds rarely exceeds 2 cm. The sand grains in the formation are overwhelmingly dominated by quartz and quartzite with only a minor content of mica and heavy minerals. The formation is characterised by both coarsening-upward and fining-upward depositional patterns. The upper part is commonly characterised by a 15–30 m thick fining-upward succession from coarse-grained to fine-grained sand. The formation is characterised by a succession of sand with subordinate layers of clay that are centimetres thick. If the sand-rich succession is thicker than 5 m, intercalation of thicker mud layers may occur.

Sand of the Bastrup Formation has at present not been recovered from any offshore wells. The interpretation of the presence of the Bastrup Formation in the R-1 and C-1 wells is based on subtle gamma-ray log patterns. The lithology of the formation offshore is thus uncertain.

Log characteristics. Onshore, the Bastrup Formation is characterised by low gamma-ray readings (Rasmussen et al. 2010; plates 2, 3, 6). The log pattern is serrated and shows both decreasing (e.g. in Stakroge, 130–95 m) and increasing (Fjelstervang 107–68 m) upwards trends through the succession. The upwards decreasing trend of gamma-ray readings reflects a coarsening-upward trend associated with delta progradation and the upwards increasing trend of gamma-ray response (a fining-upward trend) is associated with channel fill deposits, for example point bars (Rasmussen 2009b).

Offshore, the Bastrup Formation is only represented by the R-1 and C-1 wells. Here, the log pattern shows subtle decreasing and increasing trends, probably associated with delta-lobe switching or deposition of storm sand layers from eroded nearshore areas (Fig. 18; Supplementary Files, Plate 4).

Fossils. The distal Bastrup Formation recorded offshore Denmark contains a variable dinocyst flora, rather sparse at some levels and rich at other levels. A low diversity, but fairly high abundance of calcareous benthic foraminifera assemblage characterises the Bastrup Formation in the R-1 well (King 1973); calcareous benthic foraminifera are rare in the C-1 well (Laursen et al. 1992; Church et al. 1968).

Depositional history. The Bastrup Formation was laid down in a fluvio-deltaic environment. The fluvial sediments were deposited in meandering systems with channel depths up to 30 m (Rasmussen et al. 2010). Based on the thickness of clinoforms, the water depth in the marine realm was up to 150 m. Due to the predominance of westerly winds, the deltas were wave-dominated with formation of spit and barrier complexes south-east of the delta outlet. Seismic data and published models for modern deltaic systems strongly indicate that the mud supplied by deltas is mainly deposited along the slope as contourites. We suggest that a significant proportion of the mud from the Bastrup delta system was laid down as contourites in the Ringkøbing–Fyn High area.

Boundaries. The lower boundary with the Klintinghoved Formation is expressed by an increasing content of sand. The gamma-ray log in the R-1 well shows an initial decrease in gamma-ray response (Fig. 18). In the C-1 well (Supplementary Files, Plate 4), the boundary is characterised by a distinct decrease in gamma-ray log readings. In the R-1 well, the upper boundary is defined by an increase in gamma-ray readings, representing the transition from the sand of the Bastrup Formation to the overlying mud-rich Arnum Formation.

Distribution. The Bastrup Formation is recognised in central, western and southern Jylland. In the North Sea, the western limit, or pinch-out, of the formation probably coincides broadly with a NW–SE-striking line running just west of the R-1 well, but no other data exists apart from those from R-1 to confirm this (Fig. 18; Supplementary Files, Plate 4).

Biostratigraphy. The Sumatradinium hamulatum dinocyst zone and the lower part of the Cordosphaeridium cantharellus dinocyst zone have been recorded in the Bastrup Formation (Figs 1, 9; Dybkjær & Piasecki 2010).

The calcareous benthic foraminifera zone NSB10 (King 1989) has been recorded in the Bastrup Formation in the R-1 well (Fig. 9; King 1973; Laursen et al. 1992).

Geological age. The Bastrup Formation comprises deposits of early to mid-Burdigalian (Early Miocene) age.

6.1.3 Arnum Formation

revised formation

History. The Arnum Formation was defined by Sorgenfrei (1957) and revised by Rasmussen et al. (2010) to represent the mud-rich marine succession overlying the Bastrup and Klintinghoved Formations.

Name. After the village of Arnum in southern Jylland (Fig. 2).

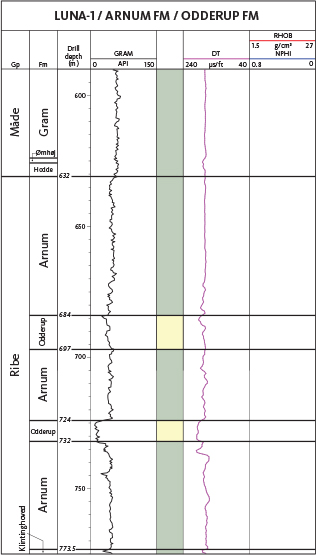

Type and reference sections. Two boreholes at Arnum (DGU no.150.13, DGU no.150.25b; both at 55˚14′48.07″N, 8˚58′18.48″E), 107 to 40 m and 107.5 to 40 m MD respectively, together form the type section (Sorgenfrei 1957; Rasmussen et al. 2010). The North Sea reference section is the Luna-1 well (56˚05′57″N, 5˚52′53″E) from 773.5 to 632 m MD intercalated with two intervals of the Odderup Formation, 732–724 m and 697–684 m (Fig. 19).

Fig. 19 The Luna-1 well is the North Sea reference section of the Arnum Formation, from 773.5 to 632 m MD and the Odderup Formation, from 732 to 724 m and 697 to 684 m MD. For legend, see Fig. 14.

Thickness. The Arnum Formation is generally up to 100 m thick (93 m in the type section) but ranges up to 140 m thick in the westernmost part of the Ringkøbing–Fyn High area.

Lithology. The Arnum Formation is composed of dark brown mud, commonly with shell beds. Laminated, fine-grained sand beds are common. The clay assemblage consists of 50–60% kaolinite, c. 20% of both smectite and illite and up to 10% chlorite (Nielsen et al. 2015).

Log characteristics. The formation is characterised by medium to high gamma-ray values and shows a serrated pattern. At some levels, it shows sections characterised by upwards decreasing gamma-ray readings (e.g. in Luna-1, 753–744 m and 643–635 m).

Fossils. The Arnum Formation is characterised by a rich and diverse dinocyst assemblage. In the Luna-1 well, high abundance and diversity calcareous benthic foraminifera assemblages and high abundance, low diversity planktonic foraminifera assemblages are present. Agglutinating foraminifera are present in higher diversity assemblages than in the intervals below and above. Bolboforma (insertae sedis, calcareous phytoplankton) are rare. Other microfossils include rare diatoms, Radiolaria, sponge spicules, fish teeth and shell debris (Rasmussen et al. 2015).

Distribution. The formation is distributed in west and southern Jylland and in the Ringkøbing–Fyn High area. In the western part, near the Central Graben, the formation interfingers with the upper part of the Dany Formation and with the Nora Formation. The boundary between the distributional areas of the Arnum and Dany Formations is arbitrarily placed at the eastern margin of the Central Graben. The boundary between the Nora Formation and the Arnum Formation is more well-defined as no diatomite-rich muds have been detected in any wells east of the Central Graben (Fig. 20).

Fig. 20 Distribution of the Odderup, Arnum, Dany and Nora Formations (stratigraphic interval indicated by red box), illustrated in terms of their dominant sedimentary associations: the floodplain sediments and the channel, swamp, delta, shoreface and offshore sands are referred to the Odderup Formation; the offshore mud is referred to the Arnum Formation; the slope mud and deep marine mud are referred to the Dany Formation; the offshore diatomite is referred to the Nora Formation. Neogene deposits of this age have been removed by erosion east of the truncation line indicated in the offshore area; the distribution of sedimentary associations east of this line (and north-east of the onshore outcrops/wells) is hypothetical. The striped belt indicates areas that are inferred to have experienced shifting depositional settings during the late Burdigalian – early Langhian.

Depositional environment. In the eastern part of the study area, the Arnum Formation was deposited in a shallow-water environment in front of a coastal plain (Odderup Formation). In the marginal marine area, the formation interfingers with fine-grained sand beds enriched in heavy minerals. In distal settings, a shelfal environment prevailed and sedimentation of mud dominated.

Boundaries. In the offshore area, the lower boundary is defined by a distinct spike/peak of low gamma-ray readings (Fig. 19; Supplementary Files, Plate 4) and a distinct change in the velocity log. These spikes correlate with the top Klintinghoved seismic marker (Fig. 12). Onshore, the boundary is lithologically characterised by a change from brown mud-dominated sediments with intercalations of greyish silt and fine-grained sand of the Klintinghoved Formation to dark brown mud. Offshore, the boundary is not documented in core.

The upper boundary is very distinct, being placed where the gamma-ray log shows a prominent shift to high gamma-ray values (Fig. 19; Supplementary Files, Plate 4). Onshore, the boundary is seen as a shift in colour from brown to dark brown clay, as illustrated by the Sdr. Vium core. No cores exist from this boundary in any offshore wells, but studies of cuttings indicate that a similar change in the colour of the mud is seen here. On seismic data, the boundary forms a prominent seismic reflection in most of the Danish area. Local unconformities associated with slope failure are recognised locally, especially in the middle part of the Ringkøbing–Fyn High area near the S-1 well (Huuse et al. 2001).

Biostratigraphy. The Arnum Formation in the Luna-1 well comprises the following dinocyst zones: the Exochosphaeridium insigne Zone, the Cousteaudinium aubryae Zone and the Labyrinthodinium truncatum Zone, except for the uppermost part (Dybkjær & Piasecki 2010; Rasmussen et al. 2015) (Figs 1, 9).The calcareous benthic foraminifera subzone NSB10II (Laursen & Kristoffersen 1999) has been reported from the Arnum Formation in the Luna-1 well (Fig. 9; Rasmussen et al. 2015).

Geological age. Mid-Burdigalian – early Langhian (Early Miocene – early Middle Miocene).

6.1.4 Dany Formation

new formation

History. The Dany Formation corresponds broadly to the lower part of the upper Lark Formation (L4) as recognised by Schiøler et al. (2007). The Lark Formation was defined in the UK sector by Knox & Holloway (1992) and adopted by Schiøler et al. (2007) to represent the Upper Eocene to lower Middle Miocene brownish grey mudstones of the Danish North Sea. Based on seismic and log stratigraphy, Schiøler et al. (2007) recognised four informal units in the Lark Formation (L1–4). L4, the uppermost unit, is formally reassigned here to the Ribe and lowermost Måde Groups; the Dany Formation is the basal formation of the Ribe Group in the Central Graben area (Fig. 8). Note, however, that the stratigraphic definition of the base of the Dany Formation (and hence the Ribe Group) in this area differs slightly from the base L4 definition given by Schiøler et al. (2007), as discussed further under ‘Boundaries’ below.

Name. After the Dany-1 well (Fig. 2).

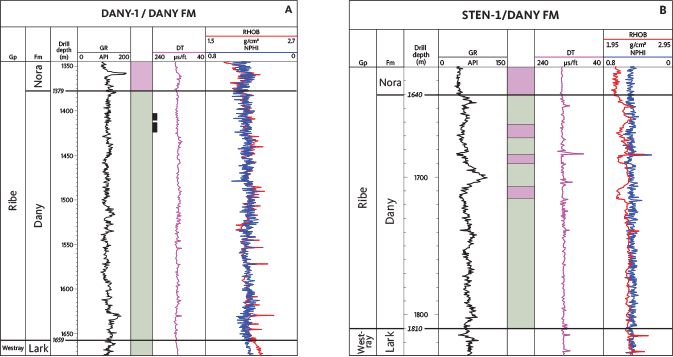

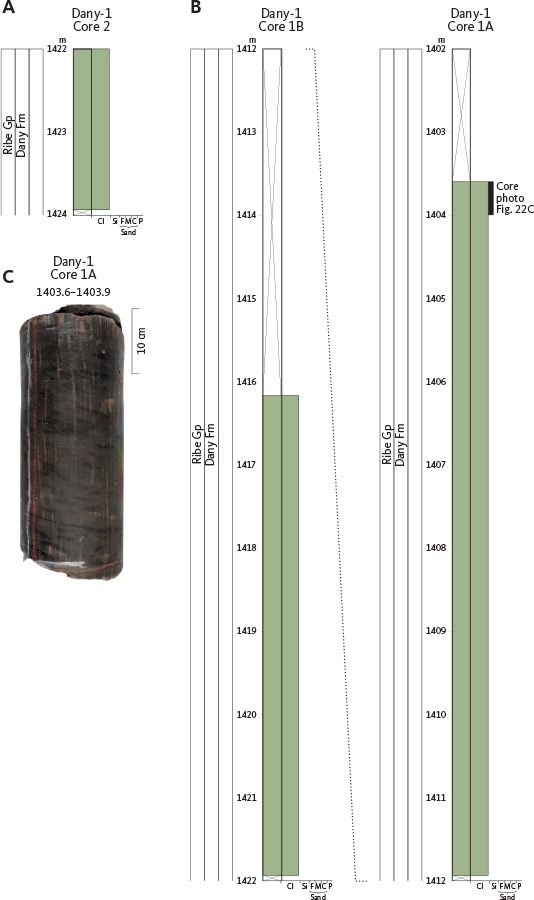

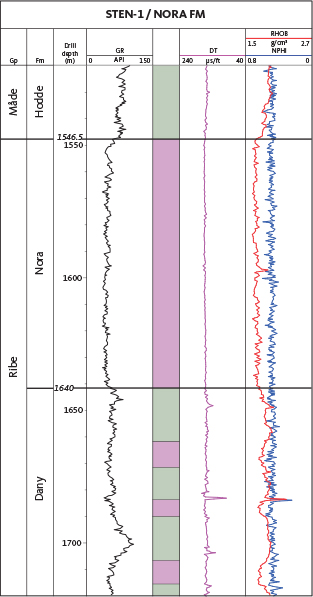

Type and reference sections. The type section is the Dany-1 well (55˚24′18,94″N, 5˚9’38.02″E) from 1659 to 1379 m MD (Fig. 21A). The reference well is Sten-1 (56˚07′47,718″ N, 3˚37′34,687″ E) from 1810 to 1640 m MD (Fig. 21B). Part of the section was cored in the Dany-1 well (55˚24′18.94″N, 5˚9′38.02″E) from 1424 to 1403.60 m (core depth; Fig. 22).

Fig. 21 (A): The type section for the Dany Formation is the interval between 1659 and 1379 m MD in the Dany-1 well. Cored interval is indicated by a black bar. Note that there is no crossover of the neutron-density logs in the Dany-1 well as there is less diatomite in the southern part of the Danish sector. (B): The reference section is the interval between 1810 and 1640 m MD in the Sten-1 well. For legend, see Fig. 14.

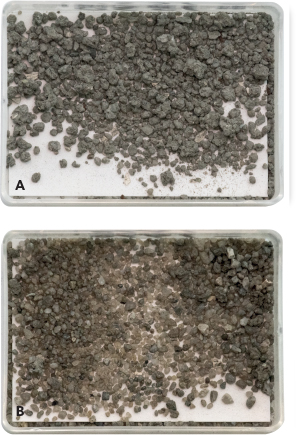

Fig. 22 Measured cored section of the Dany Formation in the Dany-1 well. (A): Core 2 and (B): Core 1A and 1B – see location on Fig. 21A (black bar). (C): Photo of the uppermost part of the core (depth interval in metres). The state of these cores is rather poor due to intense sampling activity; sedimentary structures and lithology variations are therefore obscured. For legend, see Fig. 14.

Thickness. The Dany Formation is 280 m thick in the type well, and thicknesses between 250 and 300 m are common; it is up to 500 m thick in the northern part of the Central Graben area.

Lithology. Dark brown to blackish brown mud (Fig. 22). Intervals with grey and greenish brown mud occur. In the northern Danish Central Graben, grey diatomite-rich intervals are common. The content of organic matter is relatively high, varying between 3% and 7%. The clay mineral assemblage is 40–70% smectite, 20–30% kaolinite and 10–30% illite (Nielsen et al. 2015). The content of smectite is highest in the southern part of the Danish Central Graben.

Log characteristics. The gamma-ray log shows a serrated pattern with some high readings in the lower and upper parts of the formation. The neutron-density logs are typically superimposed (Fig. 21A), contrasting with the underlying Lark Formation, which shows a clear separation. The overlying Nora Formation is characterised by cross-over of the neutron-density logs (Fig. 21B; Supplementary Files, Plates 1 and 9), reflecting the low density of the diatomite component. In the Dany-1 well, such a log cross-over is not seen in the Nora Formation due to less diatomite in the southern part of the Danish sector (Fig. 21A).

Fossils. The lowermost part of the Dany Formation is characterised by a rather poor and low-diversity dinocyst assemblage in the Alma-1 and Frida-1 wells (Schiøler et al. 2005; Dybkjær & Rasmussen 2007). The overlying (major) part of the Dany Formation is characterised by an increasing – from low to moderate – abundance and diversity of dinocysts.

The lower Dany Formation in the Dany-1, Frida-1 and Luna-1 wells is characterised by high abundance agglutinated foraminifera assemblages with varying diversities. Calcareous benthic and planktonic foraminifera are absent to rare. Radiolaria, diatoms and sponge spicules are present (Mears 1997; Dybkjær et al. 2012; Parker & Pedder 2014; Rasmussen et al. 2015). In the upper part of the Dany Formation, agglutinated and calcareous benthic foraminifera are common in the Frida-1 well, and diatoms are common in Luna-1 and Frida-1 (Mears 1997; Rasmussen et al. 2015). The Dany Formation in the Sten-1 well displays high abundance and diversity diatom assemblages (siliceous preservation) with common Radiolaria, Bolboforma and sponge spicules and relatively low diversity calcareous benthic foraminifera assemblages and generally rare agglutinated and planktonic foraminifera (see also Bailey 1983).

Depositional environment. The formation was deposited on the basin floor in water depths of more than 600 m. The lowermost part of the Dany Formation is characterised by an impoverished dinocyst assemblage, dominated by the genus Homotryblium; this probably reflects a low-salinity, restricted basin comparable to the recent Baltic Sea.

Boundaries. The lower boundary is characterised by a change from dark, greenish clay to dark brown mud, as seen in ditch cuttings samples, and further correlates with a regional seismic marker (Figs 11, 12). This seismic marker corresponds to the Oligocene–Miocene boundary (Dybkjær et al. 2012).

On gamma-ray logs, the character of the boundary is variable with some wells displaying a distinct increase in gamma-ray readings, whereas others show a distinct decrease in gamma-ray response. The neutron-density response, in contrast, is very uniform and shows an amalgamation or distinct narrowing of the two logs at the boundary (see Fig. 21A; Supplementary Files, Plates 1 and 9). The lower boundary is also commonly characterised by a distinct change in velocity from lower to higher sonic readings, indicating more compacted sediments below the boundary.

In the Central Graben area, the lower boundary of the Dany Formation correlates with the top of L3 of Schiøler et al. (2007), for example in the Alma-1 well (see Supplementary Files, Plate 6, and Schiøler et al. 2007, their plate 4), which is interpreted as correlating with the Oligocene–Miocene boundary (Dybkjær et al. 2021). However, on the Ringkøbing–Fyn High, the boundary in this study is placed on top of the Freja Member as this correlates with the Oligocene–Miocene boundary at the type section, the Lemme–Carrosio section, in Italy (Dybkjær & Rasmussen 2007; Dybkjær et al. 2012). According to Schiøler et al. (2007), however, the Freja Member is included in their L4 unit. Consequently, there is a discrepancy in the placement of the lower boundary of the Dany Formation and the top of L3 of Schiøler et al. (2007) on the Ringkøbing–Fyn High where the Freja Member is present.

The Oligocene–Miocene boundary proposed by Dybkjær et al. (2012), which correlates with a distinct seismic unconformity in the North Sea area, is typically located some tens of metres higher than previously reported. For example, in the Kim-1 well, we recognise this boundary at 1828 m, whereas Schiøler et al. (2007) placed it at c. 1905 m (their fig. 51); in the Mona-1 well, the boundary was placed at c. 2015 m by Schiøler et al. (2007) but we recognise it at 1940 m.

The upper boundary shows an abrupt decrease in gamma-ray values, particularly in wells from the north-western part of the Danish sector, for example in Sten-1 (Figs 21A, B; Supplementary Files, Plate 1). On the neutron-density logs, the upper boundary is often characterised by the onset of a cross-over. In cuttings samples, there is a clear change in colour up-section from dark brown and brown to grey mud.

Distribution. The Dany Formation, as defined in this study, is restricted mainly to the Central Graben area and represents the distal correlative of the Klintinghoved and Arnum Formations (Figs 17, 20; Supplementary Files, Plate 4). The boundary between the Dany Formation and the Klintinghoved/Arnum Formations is arbitrary. A thin succession is referred to the Dany Formation in the westernmost part of the Ringkøbing–Fyn High area, for example in the Luna-1 and Frida-1 wells (Supplementary Files, Plate 4).